Operation Pawan’s remains largely unacknowledged despite its significant human cost

Mohammad Asif Khan

In October 1987, a contingent of Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) soldiers embarked on a hazardous mission to Jaffna University in Sri Lanka, where key leaders of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) were believed to be hiding. The aim was to swiftly capture these leaders, but the operation faced immediate difficulties. As helicopters carrying the troops approached the university, they encountered intense gunfire from LTTE fighters who had anticipated the attack. Despite the heavy resistance, the soldiers pressed on with determination.

The situation quickly deteriorated. The operation, initially planned to last 90 minutes, extended as only a fraction of the soldiers were able to land and engage the enemy. The rest faced severe obstacles, including relentless enemy fire and difficult terrain. By dawn, it was evident that the mission had exacted a heavy toll. Many soldiers were either killed or captured, reflecting the immense bravery and sacrifice of those involved.

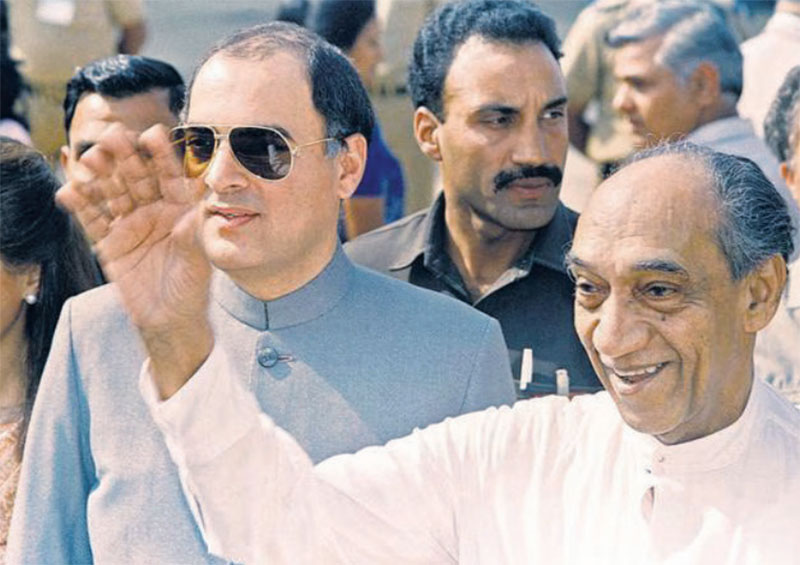

These soldiers were part of Operation Pawan, an ambitious military initiative by the IPKF aimed at disarming the LTTE and restoring peace in Sri Lanka. On 29 July 1987, Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi signed the India-Sri Lanka Peace Accord, leading to the deployment of Indian troops to safeguard Indian interests. This marked the beginning of Operation Pawan.

Operation Pawan continued for three years, with Indian troops beginning their withdrawal in 1989 and completing the pullout by March 1990. The operation resulted in significant casualties, with around 1,200 Indian soldiers losing their lives and many more injured. While it succeeded in taking control of key LTTE-held areas, including Jaffna, it ultimately failed to establish lasting peace. The LTTE continued their insurgency, leaving the conflict unresolved and the situation in Sri Lanka still volatile. This difficult and costly intervention is why Operation Pawan is often referred to as ‘India's Vietnam.’

Perhaps, this is the reason Operation Pawan is not widely commemorated in India. The government has not officially recognised or honoured the operation with dedicated events or memorials, resulting in a lack of public acknowledgement of the troops’ courage. Despite this, veterans and their families have endeavoured to honour their comrades privately. They sought and received permission from the government to pay tribute at the National War Memorial. However, the approvals granted in 2021 came with conditions: only a silent ceremony would be allowed, no serving officer in uniform could attend, and a wreath could be laid only by the senior-most officer present.

On July 29 this year, a silent ceremony was held at the National War Memorial for the fourth consecutive year. A small gathering of veterans and families honoured the martyrs, but no minister or elected representative of India attended the commemoration event.

Talking with FORCE, Colonel R.S. Sidhu (retd), Sena Medal, a veteran of the operation, said, “Despite the number of martyrs in Operation Pawan (1,171) being significantly higher than those who died in the Kargil War (around 530), the veterans of Op Pawan are still denied a formal day of commemoration at the National War Memorial. It is ironic that while the Indian military neglects to honour its Op Pawan veterans with a formal commemoration, the Sri Lankan government has built a grand War Memorial in Colombo to recognise the supreme sacrifices of the IPKF troops, where wreaths are laid twice a year.”

Operation Pawan was initiated to implement the Indo-Sri Lanka Agreement (ISLA), signed on 29 July 1987, between Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and Sri Lankan President J.R. Jayewardene. The ISLA aimed to end the Sri Lankan civil war by establishing a framework for devolving power to Tamil-majority regions and ensuring the disarmament of Tamil militant groups, including the LTTE.

Operation Pawan was not a conventional military engagement but a complex politico-military mission. The IPKF was invited by the Sri Lankan government to ensure adherence to the ISLA by both Sri Lankan security forces and Tamil militants. The agreement sought to address the Tamil minority’s grievances, including the merger of the Northern and Eastern Provinces, holding general elections and a referendum on the merger. However, the deployment timeline, commencing just a day after the ISLA’s signing, allowed no time for strategic planning or preparation. As Colonel Sidhu notes, “The force earmarked for conventional offensive operations was launched on a peacekeeping assignment, without any further thought, revised plans, briefing, etc.”

The immediate trigger for the operation was the humanitarian crisis in the Tamil-dominated Jaffna Peninsula, where the Sri Lankan military’s offensive had caused significant civilian suffering. India, under the guise of humanitarian intervention, sought to assert its influence and prevent further violence. The initial deployment of the IPKF began on 30 July 1987.

The Indian Army deployed a full division, comprising approximately 50,000 troops, to Sri Lanka. The IPKF was tasked with overseeing the disarmament of the LTTE and other militant groups, maintaining law and order and facilitating the devolution of power as per the ISLA. However, the situation quickly deteriorated as the LTTE, led by Velupillai Prabhakaran, refused to lay down arms and continued to demand an independent Tamil Eelam.

The first significant operation by the IPKF was the attempt to capture the LTTE leadership in Jaffna. Launched on 12 October 1987, this operation involved a daring airdrop of troops onto the Jaffna University campus, suspected to be an LTTE stronghold. The operation faced severe logistical challenges, including limited landing zones and heavy resistance from well-entrenched LTTE fighters. Despite deploying 418 soldiers using Mi-8 helicopters, the operation encountered unexpected difficulties, with many soldiers landing away from their intended drop zones.

You must be logged in to view this content.