The War Zone

Following up on the inaugural cover story of FORCE, here is another treasure from our archives. In November 2003, FORCE team spent a week in the Jammu division of Kashmir. Starting with the Rashtriya Rifles’ Delta force headquarters in the Doda sector of Jammu division to get first-hand experience of Indian Army’s counter-insurgency operations, the December 2003 cover story included interviews with chief minister J&K Mufti Mohammed Sayeed, chief secretary Sudhir Bloeria, Northern Army Commander Lt Gen. Hari Prasad, Director General, BSF Ajai Raj Sharma, Inspector General, BSF, Jammu division, Dilip Trivedi, Inspector General CRPF, Jammu Division, C. Balasubramaniam and countless unnamed officers from across the uniform. Field reporting at its best. Read on.

The proxy war in Jammu & Kashmir gets murkier

Pravin Sawhney and Ghazala Wahab

The mountain wildflowers were blooming. But the lone ranger trudging at the height of nearly 12,000 feet had no time to stop and admire their myriad colours. It was just about enough to stay alive. The times were difficult and the mountains with inhospitable heights, deep crevices, sharp slippery rocks and unpredictable weather were no longer the safe haven they used to be. Once upon a time, it was only man against the nature. However, now nature colluded with men against men depending upon whose good day it was.

Just as the solitary man moved stealthily from behind one rock to another an old woman with some cattle hobbled towards him, equally stealthily. Drawing his face closer to hers, she whispered, “Son, don’t go west. A few army men are patrolling that area.” He pulled away in surprise. How did she know they were army men? Obviously, they were not careful enough. He should have a word with the men about this. Thanking the old woman, Major Aditya Kumar disappeared in the hedge to the east.

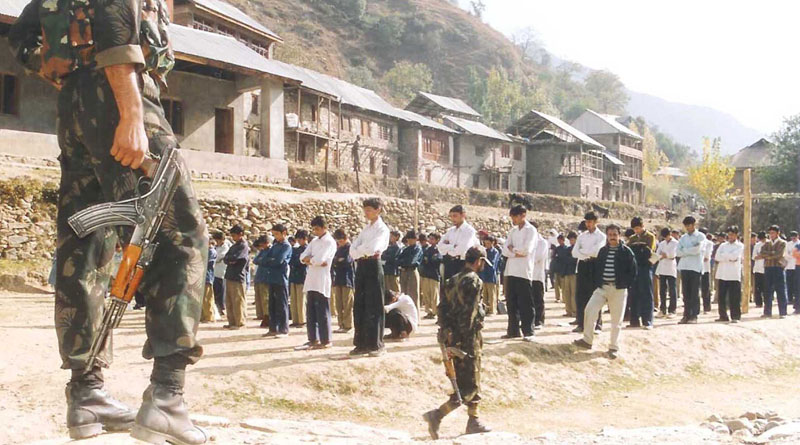

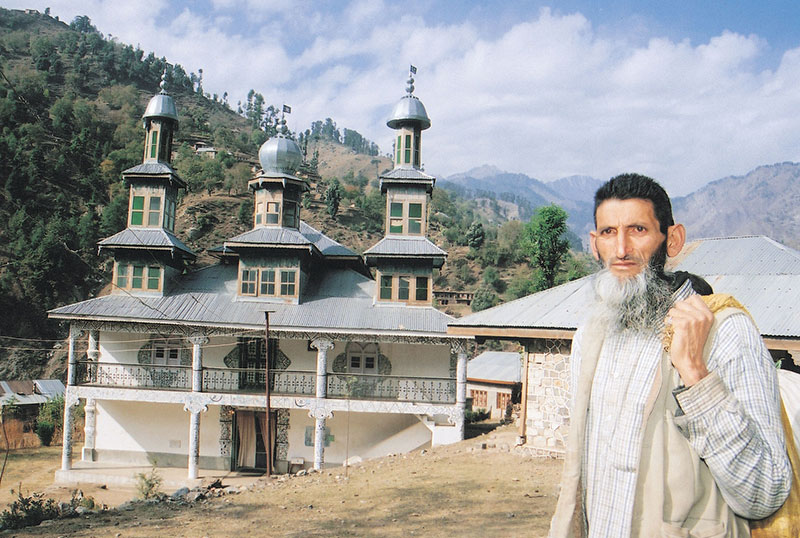

With long unkempt hair, a typical Muslim beard that starts a little below the lower lip and a pencil slim moustache, Kumar looks every bit a local Kashmiri who has spent many days in the mountains without a bath. His AK-47, a low sling bag with rations, long shapeless kameez and salwar completes his look of a terrorist. Depending upon who he comes across, he alternatively passes himself off as a Kashmiri militant or an Afghan terrorist. The important thing however is, to speak as less as possible. The language is a big giveaway. Even if you get the language right, getting the accent correct is a challenge most young officers don’t want to take on. Fighting the proxy war in Jammu and Kashmir has become something of a game now. A very dangerous game, mostly with fatal consequences for the militants. And just as with any other game, this one is also fraught with its high and low moments, good and bad days. The 23 Rashtriya Rifles battalion, currently located in Nachlana village of the Doda district of Jammu has become past-masters at this game. All the young officers and men are encouraged to grow their hair and look as much like a local person as possible. Not that they need too much of prompting. Most of them are happy to play the game at the terms of the militants on their turf and then savour the pleasure of defeating them. They call it pseudo operations and relish lulling the militants into a false sense of security. Apart from looking like a local, many even behave like one. Some of them carry prayer mats with them as is wont with the militants while some hang around the mosques, pretending to be fasting in the holy month of Ramadan. And it is not only the officers who are doing this. Even the men have been so charged with the idea that many spend days with villagers breaking the fasts with them and gauging the mood. The idea is not only to kill terrorists (though that remains the priority number one) but also to gather intelligence from the locals and generally keep abreast of popular sentiments.

“We have surprised quite a few militants in our pseudo operations,” says one young major, veteran of many such operations and a hero in his battalion. “When they see us from a distance they cannot often tell who we are.” The major, who can easily slip into the gear of a rock singer, is particularly popular among young village women who take him to be a senior Afghan commander. While many have come forward to kiss his hands, others have made enquiries about him from his men, many of whom are locals. “I don’t talk because I can’t speak their language very well. So I stay aloof, which suits me fine. It helps in building a formidable image,” he says with a mischievous smile. Most of the RR officers are accompanied by Special Police Officers (SPO), who are local men recruited for a couple of thousands. These men are given the basic training in weapons before they start accompanying RR on operations. Their primary job is to act as guides, interact with the locals and cull information. Because of their attire and general appearance they can easily pass off as militants also.

It is clear that the proxy war in Jammu and Kashmir has entered a new, ruthless phase, where all the parties involved are determined to fight the old battle with a new, multi-pronged strategy. And in this battle one of the key ingredients is giving as much of a free hand to young, enthusiastic officers (many of whom have opted for a second term in these areas) as possible. For example, one day an RR major from the 23 battalion was itching for action. He hadn’t had much success with terrorists lately. So, along with a few of his men and basic rations he left for the mountains to search for the terrorists. He had no preliminary information and no leads. But since the Pir Panjal ranges are notorious for being safe haven for terrorists he decided to take his chance. He and his men scoured the ranges for days, between 8,000 to 11,000 ft, often living on just a few namakparas and enough water to keep the throat moist. But without luck. Every now and then they would see a few terrorists from a distance with their binoculars but by the time they would come close enough to engage them (which would often take a day or two of walking given the topography) they would have slipped through the rocks or the hedges. Often the terrorists would see them first and disappear in thick foliage.

“This carried on for nearly 20 days,” recounts the major. “Finally I told my men and my headquarters that irrespective of our luck with the terrorists we would return on the 23rd day to mark 23 RR.” But then, lady luck finally relented and suddenly they came across two terrorists trudging up the mountains, probably towards their hideout. One of them had a radio communication set with him while the other had a weapon. The major and his men hid behind the rocks as they didn’t want to prematurely expose themselves thereby causing the men to escape once again. Gradually fanning out behind the trees, the shrubs and the rocks, they started encircling the militants. Once they were close enough, (close enough would still mean a few 100 metres away in uneven ground, bushes, rocks etc where visibility is a matter of chance) they opened fire. “The terrorist with the radio set was some kind of a commander and the one with the weapon was his deputy. Despite being taken by surprise the two immediately ducked though we had managed to injure the commander,” recalls the major.

The sporadic gun battle lasted a few hours and ended with the killing of the two militants. “But these guys are so good with the terrain that one moment you see them and the next they are not there,” his colleague, also a veteran of many such operations, adds. Hence, killing or catching a militant in these areas is a very tricky job. The terrorists don’t want to attract attention to themselves in these areas, which are often close to their various hideouts. They’d rather merge with the scenery and slither past the security forces. They don’t want to engage them in any gun battle and often don’t even retaliate with fire if it means getting an escape route. A common practice is to hide the weapon if you see the forces closing in and pretend to be a villager or a shepherd. “Sometimes, if there’s a nullah or something they’d just jump without caring for the height,” says a captain.

Despite better weaponry, superior gear and good intelligence, the odds are stacked heavily against the security forces. A local militant is familiar with the area like the back of his hand. And even if the terrorist is a foreigner, locals who lead him through patches, curves and crevices that no security man would have seen accompany him. As one former police superintendent points out, “Any security personnel’s experience in the region at best would be about one-and-a-half years. How can he match the terrorist in his knowledge of the region, the people, their customs and even their experiences?”

Also Read:

The Line of (no) Control

In July 2003, FORCE editors Pravin Sawhney and Ghazala Wahab travelled along the

Line of Control to get a sense of life in the line of fire. This was before the ceasefire.

16 years later, we seem to be back in those times.

So that we don’t forget what life meant without the ceasefire,

we are reproducing that article

Another disconcerting fact for the security forces is the silent support that the militants enjoy. It would not be entirely correct to say that people completely support the militants, but they are certainly sympathetic towards them. They may not offer them refuge or assistance or even manpower, but they don’t wish them dead either. After all, many are their own blood. Hence, as far as possible, there are many who forewarn the militants of the security forces’ operations. It is true most people want peace, but too much of their own blood had flown down the parched tracks of their villages for them to wholeheartedly support the security forces’ operations.

This is one reason why intelligence gathering has been such an arduous task in Jammu and Kashmir. Despite the pseudo operations and the larger than life presence of the security forces the fear of the militants is all too real, as are the reprisals for those whom they suspect of being informers. Hence, the overall strategy of the army and the paramilitary for combating insurgency includes winning over the people and instilling in them a sense of confidence towards the security forces.

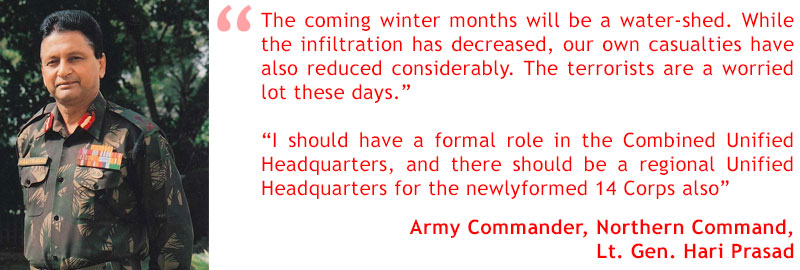

The Frosty Winter

Lt. Gen. Hari Prasad, army commander, northern command sums up the Counter Insurgency (CI) operations in the state in a single sentence: “The coming winter months will be a watershed.” He is not alone in his optimism. The optimism bubbles are trickling down to the youngest officer in the state who is now gripped with the idea of fighting terrorists. But just as his army commander means, he understands that successful CI operations involve more than killing terrorists. An equally important aspect is to bring back the alienated people of the state into the national mainstream. Considering that enough transparency and behind the scene preparations have been afoot since the end of Operation Parakram on 16 October 2002, the general’s assessment needs to be taken seriously.

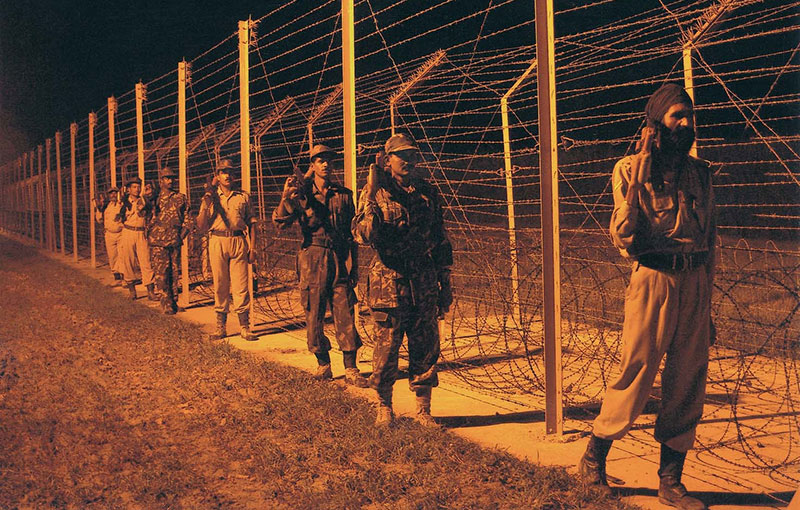

First and foremost, additional troops, which were inducted into J&K during the 10-months long Operation Parakram have not returned to their permanent locations. In addition to their operational roles, these nearly two divisions worth of troops are available as mobile teams behind the Line of Control (LoC) to check infiltration. They reinforce the efforts of the forces on the LoC, which are dual tasked: to checkmate any Pakistani aggression across the LoC, and to kill terrorists who manage to cross into own territory. The task of these combined troops is made easier by the select fencing behind the LoC, and the availability of ground sensors and improved equipment for CT tasks. The fencing behind the LoC is in two rings with the inner ring being electrified. It is expected to be completed by January 2004.

That apart, road opening tasks, which were earlier assigned to the RR and are now given to the army and other security forces, have also undergone a sea-change. The army has the indigenously developed Ashi equipment (radius 1.5 km) to detect Improvised Explosive Device (IED), which the ROP (Road Opening Party) carry with them. The Ashi equipment can also be fitted in the South African armoured vehicle called Cassipir and in this mode it has a radius of 4km. Cassipir work in twin modes, blast and convoy, and are used for road opening throughout the national highway 1 which runs from Jammu to Srinagar. In fact, one can see Cassipir stationed every 35-40km on the highway.

The army has procured Hand Held Thermal Imagers (HHTI) which help in observation of up to two kms at night in a big way. A total of 1,100 HHTI have been delivered to troops, 1,700 more are in the process of being procured by M/s Bharat Electronic Limited, and a contract for 300 more powerful HHTIs has been signed with M/s Thales of France. The army hopes to provide each post on the LoC with at least one HHTI by the end of this year. In addition, 400 short range battlefield surveillance radars, high resolution binoculars, GP 338 Motorola sets for better communications and various imported self-defence weapons, such as, Tavor assault rifles, anti-material rifles, Galil sniper rifles and so on are already with troops in CT operations. Troops involved in CT operations have also asked for High Altitude snow gear for the coming winter, apart from the climbing equipment for snow warfare. Obviously, the winter is not going to be a quiet one. Little wonder then, the troops are bracing for a long winter, which hopefully will not be bleak for them. Smiles Lt. Gen. Prasad, “While the infiltration has decreased, our own casualties have also reduced considerably. The terrorists are a worried lot these days.”

For their CT operations, the RR has adopted a two-pronged approach of “decimation and construction,” according to the General Officer Commanding Delta force, Maj. Gen. Prakash S. Chaudhary, who is responsible for the Doda district. Explaining the anatomy of CT operations he says that they are of three kinds. The first type is based upon good intelligence, where it is essential to “hit hard with accuracy.” In these operations, there is both a need to minimise civilian collateral damage, and to make sure that terrorists do not escape. These tasks have been made easier by a decentralisation of command and better communications. According to the general, “The battalion commander is the boss on the ground, and there is no question of interference from his brigade commander. Moreover, there has been a quantum jump in our communication systems. Even when I am travelling, I know what is happening in my area.” The second type of operations is called “dominating the area”, and involves regular familiarisation of an area for the purposes of gathering intelligence and reassuring the people. Yet another type of CT operations is undertaken against marked terrorists who usually belong to the area and move around with armed escort teams. In these operations, help comes from the people and the local police who are always aware about the movement of terrorists. The key to such operations is that the people should feel that the terrorists are loosing. Maj. Gen. Chaudhary enlarges the scope of such incidents and calls them, “perception management in CI operations.” This means that the fear of the terrorists should be replaced by confidence in the security forces. This requires a “construction” effort, which involves providing medical facilities to people, helping the state administration, ensuring better road communications for far flung villages, running of schools and so on. “We, however, always keep a close watch on Over Ground Workers (OGW), who are fence-sitters. They could be anyone, contractors or even local policemen, at times who either make money through terrorists or are plain sympathisers.”

No one understands the management of perception better than the army commander. He agrees that there is a need for more transparency in CT operations and which is why the army is now utilising media as a force multiplier. “We realise the importance of the media,” says Lt. Gen. Prasad. “Even the militants use the media which leads to misrepresentation of the facts. Hence, our effort is to wean away journalists who are soft on militants. Besides, I interact with the media more often, and we make sure that journalists are taken to the scene of action as soon as possible.” The northern command indeed has accorded a high priority to a better interaction with the media. In addition to the Public Relations Officer, there is an ‘Information Warfare Cell’ headed by a brigadier whose task is to maintain channels between the media and the army commander. This, however, is just the tip of the iceberg. The command headquarters has sought a more intense interaction with the state government and other security forces in the state.

The army commander says that while the “operational control of all army troops including those on CT operations is with him, he is formally not part of the Unified Headquarters (UHQ).” The UHQ, which was conceived in May 1993, but started functioning in its present form only in mid- 1996, has had a mixed response from the various security forces and the state administration. In the words of the governor, Gen. Krishna Rao who was the brain behind the UHQ, ‘the unified concept comprised setting up a unified headquarters under the advisor (home) at the highest level in the state in order to coordinate between the security forces, intelligence agencies and civil departments concerned. At the field level, the two corps commanders (15 and 16 corps at Srinagar and Nagrota) in addition to their normal operational role of defence against external aggression, were to be responsible for antimilitancy operations in the state.’ As everything else in the state, even the UHQ underwent changes. There are now two types of UHQ meetings, combined and regional. The combined UHQ meeting is chaired by the chief minister and is held about once in two months. Besides others, the two corps commanders attend this meeting. The regional UHQ meetings are headed by the 15 and 16 corps commander respectively. In addition, there are Intelligence and Operations Groups for each region which take care of operational, tactical and intelligence issues.

As the “UHQ meetings are very useful”, the army commander is of the opinion that “he should have a formal role in the combined UHQ meetings, and there should be a UHQ regional meeting for the newly formed 14 corps (in Leh) also.” In the absence of a formal role, Lt. Gen. Prasad, however, is candid that his informal interaction with the chief minister and the state government has increased. “The chief minister interacts with me very regularly on various issues.” Even as he does not specify these issues, it is evident that he is referring to the support rendered by the army in the administration of the border and far-flung areas where the state apparatus is still virtually defunct. “The state government has announced many rehabilitation packages”, the army commander said. What he did not say was what role the army would play in implementing these schemes.

New Strategies

Unlike the army which is gearing itself to fight the CT operations better in the coming months, the Border Security Force is itching to go back to its primary task. The Director General BSF, Ajai Raj Sharma says that, “Cross-border terrorism and crossborder crime remain its main concern.” Inspector General, BSF, Jammu division, Dilip Trivedi simply reiterates this: “Our ad hoc tenure in CI operations in J&K has lasted for 12 years. We are meant for cross-border problems and not for fighting an insurgency. We hope to go back to our primary task in a year’s time.” Taking an entirely different view from that of the army, Trivedi says, “CI operations are the work of local police. When you pump in more forces in an insurgency environment, you are asking for more collateral damage.” His colleague, Deputy Inspector General SID Peter, who has spent a considerable time combating insurgency in the Valley says much the same thing but with a different spin. “The BSF is army in khaki and should always be deployed in an armed battle.” By extending this argument, the army, according to the BSF top brass, should not be involved in CT operations at all.

As the largest paramilitary force under the ministry of home affairs, the BSF with a strength of 157 battalions has 48 battalions in CI operations in J&K. The further breakdown is seven battalions in the Jammu division, 31 battalions in the Valley and one battalion is tasked to guard their own static installations in the Valley. The BSF’s biggest visibility is in Srinagar city where it has eight battalions on CI operations. According to the Group of Minister’s report which was released in February 2001, the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) was to relieve the BSF completely of CI duties by January 2003 in stages; first in the Valley and then in the Jammu division. Even as the BSF brass has become more vocal about its tasteless role in CI operations, it appears that the time-schedule of its relief has been tossed out of the window.

The state deputy chief minister, Mangat Ram Sharma, recently went public saying that he would urge the Deputy Prime Minister, L.K. Advani to review the Centre’s decision to withdraw the BSF from the Valley at this ‘crucial juncture.’ Meanwhile, seven battalions of the CRPF reached the Valley on November 4 to relieve the BSF by the end of November. Even as the CRPF has started replacing the BSF in Srinagar city, both sides are already talking of a complete take-over only by 2005.

The Inspector General of the CRPF in the Valley, V.B. Singh recently said that they were confident of replacing the BSF in Srinagar. However, his optimism was only half-heartedly shared by his counterpart in Jammu. According to the Inspector General CRPF in Jammu, C. Balasubramaniam, “The CRPF has always conducted defensive CI operations. Besides other things, the mindset would need to change if the CRPF is now to undertake offensive CI operations.” The defensive CI operations refer to protecting vulnerable areas, doing patrolling and ROP duties.

Even as the internal tussle about the replacement of the BSF by the CRPF continues, the two forces are candid about their strengths and weaknesses. The BSF speaks of its ongoing fencing of the 187km International Border in Jammu (called working boundary by Pakistan) as an achievement. “We have already fenced 90 km of the 187 km, and the infiltration from this stretch has dropped by 90 per cent,” claims Trivedi. He adds further that the idea of fencing the LoC stemmed from BSF’s success in Jammu. Commenting on the army borrowing its idea he says, “The army fencing is behind the LoC, and not on the disputed border as in the case of the BSF. How this will help in stopping infiltration is very difficult to understand.” What was, however, easy to understand was the unsaid animosity that the BSF has towards the army. Surprisingly, within the BSF, the IPS officers who occupy the top slots are more vocally opposed to the army than the BSF officers who have risen from the ranks. The one-upmanship of the IPS officers visà- vis the army brass is so palpable that it was bound to have operational fall-outs, which is why, over the years both the army and the BSF have been given different areas of operations to ensure that there is no stepping on each other’s toes. It is evident that the BSF feels that the army is high-handed in its approach. However, the army commander, Lt. Gen. Hari Prasad brushed aside these misgivings with, “There is total co-operation between the army and the paramilitary forces. In any operation someone has to be in control, so the army leads but takes others on-board.” He further says, “Probably, in Delhi people talk in terms of our-baby and your-baby, here things are not so bad.” The BSF is also peeved at the status of the RR. Refusing to be quoted, a senior BSF officer points out, “If the RR is indeed a paramilitary force, then it should come under the BSF in CI operations. Isn’t the BSF under the operational command of the army on the LoC?”

The CRPF, which is poised to replace the BSF has problems of a different kind. It has a total strength of 33 battalions in the state, divided into 11 battalions in Jammu and 23 battalions in Srinagar. In addition to working with the state police, the CRPF guards vulnerable areas in the state. These include the Raghunath temple in Jammu, the state secretariat, the Mata Vaishno Devi temple and the like. According to IG Balasubramaniam, a major CRPF expansion is on the anvil. Recruitment for an additional 22 battalions begins in December this year, so that trained manpower is available by July 2004. The CRPF, in addition, will raise 11 specialised battalions for CT tasks. “The CRPF already has weapons like the indigenous 5.56mm rifles, AK-47 rifles, and two-inch mortars. We will seek to acquire more sophisticated weaponry for offensive CI tasks,” he says. What he refuses to say is how the CRPF proposes to match the mindset, motivation, training and equipment with the terrorists. The situation becomes ominous since the CRPF is seen as a better extension of the police force. In a way, this is a boon. There would indeed be more co-operation between the CRPF and the state police which have always worked hand-in-hand. Moreover, the simmering acrimony between the BSF and the RR would give way to a better working relationship between the CRPF and the RR. The big question which hangs is can the CRPF with the police by its side match the terrorists? For the moment, no one is willing to answer this crucial question which will have serious ramifications in the near future.

The Political Ping Pong

When the Mufti Mohammed Sayeed’s government took charge in November 2002 after what was called the fairest elections ever in the state, the expectations from the new dispensation were sky-high. Probably higher than what even Mufti imagined. But the new chief minister who has just completed his first year in office knows his limitations and is trying to work around them, and according to the security forces, with reasonable success. Leaving the actual fighting and the subsequent head-counting to the security forces, the state government has put into place its scheme for winning over the hearts and minds of the people. As the chief minister himself said in an interview with FORCE, “Proxy war is just one aspect of the problem. The other is to address the grievances of the people and ensure that they get justice.”

So while on one hand the state government has allowed the security forces to fight the way they feel fit, it itself wields a velvet glove to assuage the local populace. As a first step towards that direction, a new life has been infused in the state machinery. Efforts are made to ensure that the people at the lowest and the remotest level participate in the political process. Recently, the government held panchayat elections in most of the villages of the state. Besides that, state administration is also reaching the hitherto untapped region of the state. Most districts now have a commissioner, a superintendent of police, an SSP and an SSP for traffic. In fact, recently, the civil administration apparatus was set up in the Khari region, flanked by the Riliyar and the Tanki ranges. Khari, in the Doda region had been notorious for terrorist activities and in the last 12 years had not seen a single civil administrator. Things were so bad that people used to go to the local militants in case of a dispute. Once the army moved in the area it became relatively free of the militants and now boasts of proper administrative machinery. However, there are still villages which are completely cut-off from the developed areas, so much so, that even a dirt track does not reach them. In such places, the security forces are being asked to take on the role of an administrator as well. Whether it is providing the villagers with primary health facilities, schools, transportation or telecommunications, these tasks have to some extent been delegated to the security forces. Says GOC, Delta Force, Maj. Gen. Choudhary, “The funds come from the state government, but because certain areas are so remote we play the role of the administrator also. In fact, my boys teach in schools as well.”

So the government is doing what it does best: Politics. The healing touch policy of the state government that involves giving support, employment and other benefits to families victimised by either the terrorists or the security forces has been in place for a year now. The government has also formulated a surrender policy which is now with the Centre for the financial underpinnings before it is announced. The package is likely to include a consolidated amount of Rs three lakhs to the surrendered militant, apart from a monthly stipend of Rs 3,000 and employment under the selfemployment scheme. The government is optimist that through this scheme, it will be able to win over a large number of local militants at least.

In Jammu and Kashmir, economic activity has seldom matched political activism. The new government is determined that the economic vacuum does not give more space to the separatist elements, hence the emphasis on providing jobs and other employment opportunities to the people. The people of the state have always feared that they are not ruling themselves, but are being ruled by Delhi. The present government is determined to alleviate these fears. According to the chief secretary, J&K government, Dr Sudhir S. Bloeria, “Even as the government is working towards winning over the people, it is also working in close coordination with the security forces to ensure that the collateral damage due to the proxy war remains minimal.” For this purpose, the chief minister has initiated informal interaction with the forces in the UHQ. “While nothing much has changed at the formal level, the informal interaction has become more intense,” says Bloeria.

Call it determination to fight the proxy war or simply compulsions of the ground reality but the government has even moderated its stance on the much-maligned Special Operations Group (see box); instead of disbanding the force, it has assimilated SOG with the state police, which has truly risen from the ashes, to use a cliché. From the morass of 1993, when the state director general of police made his distrust of his men clear by getting the police from the other state for his personal security to the winter of 2003, the police have emerged as one of the main components fighting the proxy war. Today, the police are tasked not only with the law and order but also anti-terrorism responsibilities. Says Gopal Sharma, DGP, J&K, “Ultimately, in the end, the police has to take on these jobs because we are a service as well as a force. We interact more closely with the people, we are more accessible and hence we have more information.” Sharma says that it is the nature of the force which implies that a police station has to remain accessible at all time. Unlike headquarters of other security forces, a police station cannot become a fortress.

According to Sharma, who incidentally is from the J&K cadre, the task before the police is three-fold: eliminate terrorists currently operating in the region, ensure that replenishment of cadre does not take place and most importantly, win over the alienated people. In addition to this, the police are also fighting the gradual criminalisation of the society. “There are many people who are settling personal scores in the garb of terrorism,” says Sharma. “Recently, a few armed people attacked a marriage party killing about seven people. Perhaps, two years ago this would have passed off as terrorist killing. But we got information that it was the case of old feudal rivalry that exists nearly in all the parts of the country.”

In the coming months the police will have more responsibility towards CT operations as BSF pulls out of CI Ops. For the moment, the Srinagar city, which was the responsibility of the BSF, will be manned by the local police and the CRPF. Sharma is confident that in the next two months, the police and the CRPF will be able to take on the Srinagar city without making any structural changes in their organisation. “In any case, CRPF has always worked in tandem with the police. Even earlier, when the SOG used to conduct counter-terrorism operations, CRP used to be their back-up force,” says Sharma. Apart from the preparations that the CRPF is going to make for its new task, the police are also in the midst of a modernisation drive. Currently the police have such equipment as area weapons, grenade launchers and rocket launchers in their armoury. They also boast of AKs and state of the art communication systems. They have six training schools in J&K and are pitching for a command training centre.

The 60,000-strong police force with 20,000 Special Police Officers (SPOs) has been working in close co-ordination with other security forces, especially the army and the CRPF. In fact, about 2,000 SPOs work with the army. Moreover, the army is also hoping to recruit about 300 SPOs in its home and hearth Territorial Army (TA) battalions. The concept of the Village Defence Committee (VDC) in the Jammu sector is also being jointly executed by the police and the army. While the state government funds the project, the local SP provides the VDCs with weapons and the army trains them. In each VDC, certain bright people are chosen for further training and they become Village Defence Guard (VDG). More churning happens at this stage and SPOs are chosen from among the VDGs who are once again trained by the army. An SPO is essentially a local hired on a monthly salary of Rs 1,500. Unlike a regular policeman, he can be dismissed without notice.

Says Sharma, without a grain of modesty, “Most of the success that the security forces have had in these years has largely been because of the lower level police officers. These are the people who have their ears to the ground. Unlike other forces, they’ll remain here. So nobody can match their range as far as intelligence gathering is concerned.” The J&K police force, it seems, has come full circle.

Managing the Proxy War

The real picture about India’s management of the proxy war emerges in bits and pieces from the discordant voices one hears throughout the state. The chief minister emphatically says that things are much better, even if they are not completely normal. Giving the example of the recent terrorist attack close to his house in Srinagar he says that even as the encounter was going on children were playing in the neighbourhood park and the evening strollers and shoppers were busy with their daily chores. Signs of impending normalcy? Perhaps, in Kashmiri parlance. One telling example of what can be expected in the future is the secretariat in Jammu where one has to cross three tiers of security before once comes anywhere close to the building. And this does not take into account what happens once you are inside. Interestingly, everyone involved in fighting the proxy war has his own understanding of the situation which is often in conflict with the other person. As a former police officer says, “Everyone has a solution to the Kashmir problem and hence everyone is in a hurry to work towards his solution lest somebody else succeeds with his formula. As a result, the more the things change, more they remain the same.” But things are certainly set to change if one tries to make some sense from the cacophony of ideas, opinions and solutions. Whether they change for better or worse depends on your point of view. Because it is clear, that everyone in the state, including the present government is currently working to an agenda. Even as chief minister Mufti has given a tacit nod to the security forces to kill terrorists, his stated policies are ambiguous, and hence, suspicious. Moreover, his past casts a long shadow on his present. Recently, the J&K agriculture minister, and a senior leader of his party, Abdul Aziz Zargar caused him embarrassment when he was linked with the militants who attacked Gujarat’s Akshardham temple. This gave an opportunity to his detractors to snigger that since he has always hobnobbed with the separatist elements what is there to suggest that he has broken free off his past. The dean of the social sciences faculties in Jammu University, Hari Om, who is a political watcher wonders what is meant by Mufti’s slogans of ‘the healing touch’ and ‘peace with dignity,’ when he is soft on terrorists. Even while many disagree with Hari Om’s extreme position, they point out that the chief minister is publicly evasive on how to deal with terrorists. Moreover, Mufti’s position that the Centre should hold talks with separatists without conditions reeks of a personal agenda (he does not want to displease his friends among the Hizbul, they say) which appears at variance with that of Delhi. While the latter wants peace in the state without compromising on the territorial integrity, Mufti is gripped with the necessity of consolidating his position. It does not help that the chief minister’s party has only 16 seats out of 87 in the state assembly and got only 9.02 per cent of the total votes cast. Sure enough, the chief minister’s priority is to expand his political base during his term in office, which in reality is two years more. Mufti knows that his coalition partner, the Congress, cannot have a political base in the Valley, but will remain a Jammu based party. “Mufti wants to build his party, the People’s Democratic Party, as a regional force to become an alternative to the National Conference,” says an official. So once again, the people are held to ransom to the politics of the state.

Given this, only economics can probably bring some sense to his rule: If Mufti can bring economic benefits to the people by revving up the defunct state economy and administration, perhaps a sense of well-being can be affected. Fortunately, even his die-hard critics say he is capable of accomplishing that. The bigger worry for Mufti is to balance this by ensuring that the indigenous terrorists of the Hizbul variety are not harmed too much as this would annoy both the Over Ground Workers and the people of the Valley in general, many of whose kith and kin are in the Hizbul ranks. According to an insider, “If Mufti outrightly condemns the Hizbul, which has been labelled a terrorist organisation by Delhi, he would erode his power base.” For this reason, chief minister Mufti has not once blamed Pakistan for supporting cross-border terrorism as it would displease the Hizbul. Therefore, well-meaning people in the state feel that Mufti’s much talked about surrender policy for terrorists that awaits financial clearance from the central government, will encourage terrorism instead of discouraging by making it lucrative. “To avail the benefits all a person would require to do is get hold of an AK-47 and surrender it to the government,” sniggers one critic. If one believes Mufti’s detractors that he simply cannot afford to displease the Hizbul then it follows that the Hizbul is utilising Mufti’s tenure to strengthen its cadres, something which Pakistan also desires.

The state government’s ambiguity is also impinging upon the war on terrorism being waged by the security forces. Each force is fighting terrorism as it perceives it. For example, after Operation Parakram, the army is focussed completely on CI operations. The army commander, Lt. Gen. Hari Prasad has sought a formal role in the combined UHQ. Sources point out that it was his predecessor, Lt. Gen. R.K. Nanavaty who had first sought a formal participation in the UHQ. This, however, will not be acceptable to the chief minister who would desire that the issues concerning the two regions of Jammu and Kashmir be kept separate, and, thus a bit diffused. A close J&K watcher says that the army has an obsession, “It wants clear-cut instructions, and gives clear-cut orders to make sure who is responsible for what. Such things normally do not happen in a democracy where there are always areas of grey.” In any case, as an official puts it, “It is important that terrorism in J&K should be seen to be fought by the people and the state government. The army and the paramilitary forces should only assist them. The army’s approach appears as if it is the army versus the people of Kashmir.” However, this position does not have many takers in J&K as even the chief minister Mufti prefers an informal and yet intense interaction with the army commander.

Little wonder then, the army leadership thinks that its role is central to CI operations. Since taking command of the army on 1 January this year, Gen N.C. Vij has been to the state more times than any of his predecessors. The army commander is emphatic that CI operations is a top priority, and that there will be no let up in these operations during the winter months. On the question of special forces, the army commander says that he has two battalions of special forces, which “I will use for CT operations.” The army has already sought high altitude clothing for RR troops operating at heights along the Pir Panjal range. Lt. Gen. Prasad expressed hope that, “Once the Infantry battalion’s ‘Modification 4B’ become applicable to the RR it will substantially ease manpower management.”

In addition to the CT operations, the army desires to work closely with the state administration to improve civic facilities for people along the border belt. It is another matter that the administration, wherever it exists, does not like it. Says the state chief secretary, Dr Sudhir Bloeria, “While there are no problems at the UHQ meetings, at the lower levels of administration there are some difficulties.” He further elaborates, “Rajouri has three officers of the rank of major general with about 30 years of service each, and a young IAS officer as the district collector who is coming to see me to discuss matters.” What he left unsaid was that the army was probably interfering a bit too much with the administration in Rajouri and other big towns. The chief minister, therefore, is encouraging the army to run the administration in remote areas where the state machinery remains defunct. For example, the army has taken upon itself to encourage the locals in such areas to join the ‘home and hearth Territorial Battalions.’ However, a young army major confides that the locals are reluctant to join the TAs, which basically means joining the army. “Instead, they prefer to join the state police where there are no vacancies. Joining the army could mean incurring the wrath of the militants, while many policemen are Over Ground Workers,” he explains.

Unlike the army, the paramilitary is more in sync with the state government. They do not see combating terrorism in the coming winter as any different from what they have been doing for the last 12 years. As the BSF leadership is vocal about going back to its primary task on the border, the attitude has rubbed on its rank and file which is counting days in the Valley. Even while the BSF sees some glamour in being responsible for Srinagar city, the officers admit that the present job has enervated the force. According to the BSF DIG, SID Peter, “There has been a lot of stress for the BSF in CI operations. Moreover, the troops have been away from their families for an extended duration. Considering that this is not the permanent role of the BSF, they ought to be relieved earliest.” The state chief secretary indeed sees merit in the BSF transferring its responsibilities to the CRPF. “The CRPF is more close to the police than the BSF. Moreover, the BSF and the CRPF have had a progressive deployment in cities at one point of time,” he says. The director general of police, Gopal Sharma concurs when he says that, “The CRPF is an armed wing of the police.” Chief minister Mufti, however, is evasive. He says, “This is a central government decision, which must have been properly considered.”

Despite the assurances from the state government that an early replacement of the BSF from Valley by the CRPF will not make a difference, the reality appears different. Unlike the BSF, the CRPF does not have any worthwhile intelligence gathering apparatus (called G branch). “We started the G branch about three years ago, but it will take time to build it up,” confesses the IG, CRPF, Balasubramaniam. The state government, however, feels that this weakness of the CRPF would be more than made up by the excellent intelligence with the police. There are also the questions of weapons, training and training centres with the CRPF. In the policing role, the CRPF has not known any heavy weapons like Anti-material Rifles. According to the state government, the CRPF has already started training for offensive CI operations at select BSF and army training centres. It is another matter that top army brass is not aware of any such event. More than the CRPF, it is the police which is taking its job seriously. On condition of anonymity, a senior police officer says that, “This government does not want to take hard decisions regarding terrorists, as that could mean attrition and unnecessary killing of civilians.” Even as it is hard to accept this explanation, what is clear is that the changeover of paramilitary forces would greatly help the terrorists in consolidating their position. While it may help Mufti’s political fortunes in the Valley, the central government would be the loser.

The end of Operation Parakram has closed India’s option of a war with Pakistan in the near future. This has left Delhi with the only other option of internally managing the proxy war by Pakistan, which unfortunately, has intensified for two reasons. One, President Pervez Musharraf has successfully sold the perception to his people, and especially the army, that India, during the 10-month long military stand-off, was coerced by Pakistan’s strategic assets, implying that Pakistan could now intensify its support to cross-border terrorism. And two, Pakistan’s putative success has pushed the Jihadis to work more closely with the indigenous Hizbul Mujahideen despite having their clear-cut areas of operation. As one police officer says, “While such outfits as Jaish and Lashkar indulge in terrorist violence, Hizbul is busy consolidating its network which was deeply shaken by the SOG in the mid-Nineties. Besides, that Hizbul wants to be seen as a political force as well, which is why it indulges only in political killing. Most of the NC leaders have been killed by the Hizbul.” This implies that Pakistan’s hold over the internal situation in J&K is firmer than before. With better communications, Pakistan appears to both control and direct terrorist operations inside the border state. And, the Over Ground Workers including the hardcore break-away Syed Ali Shah Geelani group of the All Hurriyat People’s Conference have got Islamabad’s message of no-peace-until-Pakistan-is-involved-intalks loud and clear. India’s new friend, the United States, has made it clear that Musharraf cannot be pushed beyond a point. He is simply too important for Washington to loose. The US state department headed by Gen. Colin Powell and the US National Security Council headed by President Bush’s confidante Condoleezza Rice are unmoved by reports in their own media and the many noises in the Congress that Musharraf is untrustworthy in his commitment for the war on terror. Worse, the US leadership feels that India should start meaningful talks with Pakistan in return for a temporary cessation of crossborder terrorism by Musharraf. This has been US’ consistent policy post-9/11 for the sub-continent. Each time there has been pressure on Pakistan, Musharraf has scored brownie points with the US by taking temporary corrective action. He did this in his famous speech on 12 January 2002, and his commitment made to the US on 27 May 2002, when he promised to leash the terrorists. He banned Jaish and Lashkar tanzeems, only to allow them to assume new names. Under US pressure, the newborn Jaish called Khudam-ul Islam was proscribed under Pakistan’s Anti-Terrorist Act on 15 November 2003. It is anyone’s guess that they will re-discover themselves soon. Therefore, to India, four things are evident. President Musharraf will continue unabated with cross-border terrorism, his control over various tanseems and Over Ground Workers in J&K is firmer, the US will keep pretending that Musharraf is doing no wrong in J&K, and the war option with Pakistan is closed.

Against this backdrop, India cannot afford to not talk with Pakistan indefinitely as it would effect the bilateral burgeoning co-operation between India and the US. However, talking to Pakistan from a position of weakness when India is not in control of the internal situation in J&K would be counter-productive. And it is well established that piece-meal inducements to terrorists in J&K do not work well. For example, Indian intelligence agencies gave a blow to the Hizbul when its commander in J&K announced a ceasefire on 24 July 2000. The then home minister, L.K. Advani immediately referred to the Hizbul cadres in J&K as “our own boys.” Unfortunately, the ceasefire was short-lived and the commander, Abdul Majid Dar, subsequently paid with his life, making it amply clear that Pakistan controlled India’s largest indigenous terrorist outfit. India’s efforts to announce a Non-Initiation of Combat Operations by security forces, a sort of ceasefire, on 18 November 2000 during the holy month of Ramadan, which was extended thrice, bore little results. Killings by terrorists increased and the security forces were severely handicapped. Similarly, recent efforts by India to break the Hurriyat seem to backfire. Pakistan, the Jihadis and the Hizbul have declared that they back the hardliner Geelani who, at Islamabad’s behest, has been anointed as the chief of Hurriyat by the Organisation of Islamic Conference. Though the Deputy Prime Minister had indicated on October 22 that he could start talks with the Abbas Ansari-headed Hurriyat group, there are little doubts that they would be a nonstarter. Mr Advani has said that talks would be about devolution of power alone, and the already tarnished Ansari group would join them at their own peril of going into oblivion.

Interestingly, these political events in J&K would affect the Centre and Mufti’s government in different ways. The Central government would find it increasing difficult to start meaningful negotiations with Pakistan until the internal situation in J&K is under control. All it can do under intense US pressure is to play a diplomatic ping pong with Pakistan like the recent 12 point peace proposals sent to Islamabad. Genuine internal peace in J&K requires three things. One, the security forces should come heavily on terrorism to bring it down to insignificant levels. The army is keen and ready, but the paramilitary forces, the BSF and the CRPF, are not as they are caught in a baton exchange. Two, the government of India should unambiguously say whether internal political talks would be unconditional or with strings attached. With General Elections in 2004, the Centre would not like to be perceived as being soft on terrorists, even the indigenous ones. And three, attempts by Indian intelligence agencies to create fissures within the Hurriyat and the Hizbul will backfire like earlier times. Worse, they would only help reinforce the view amongst the people that Delhi and not Srinagar runs the state. Considering that this is the root cause of the insurgency, it will help Pakistan’s cause to create more Over Ground Workers in the Valley. The more mistakes the Centre makes, the more it would help chief minister Mufti to expand his power base in the Valley. It is indeed ironic that while Delhi may boast of having conducted the most fair and free elections in the state, it has thrown up an insecure government. It logically follows that the present state government would endeavour to make itself secure before it starts thinking about others. This, however, would be at a great cost.

Also Read:

Power Packed

Rashtriya Rifles have come a long way since its inception

Also Read:

Force Deconstructed

From terror-busters to terrorists. How SOG acquired a bad name