The Line of (no) Control

In July 2003, FORCE editors Pravin Sawhney and Ghazala Wahab travelled along the Line of Control to get a sense of life in the line of fire. This was before the ceasefire. 16 years later, we seem to be back in those times. So that we don’t forget what life meant without the ceasefire, we are reproducing that article

The mountains straddling the Line of Control are beautiful and inviting, but the invitation is steeped in deception. Lieutenant Mehta (not his real name, of course), has been, in his own words, doing the ‘parikrama’ of these challenging ranges for the last one month and he is still learning which peaks are friends and which are foes. You can’t blame this on his ineptitude, because, the LoC defies logic.

Though it is conveniently called a line, on the ground it breaks all the laws of linearity. It follows no regular principles, such as, watershed in the mountains, defined natural features in the plains, or river edges. The meandering, and at places militarily illogical, LoC moves mindlessly on mountain spurs with a few high and low posts held by opposing sides on a single mountain. It is not uncommon to find an Indian post in a depression surrounded by Pakistani ones on a high ground and vice-versa. Some posts are as close as 100 metres of each other. Apart from causing geographical divisions, such as, mountains, farmlands and rivers, the LoC has divided families, with one half living across the line which has known no control ever since it came into being.

Given the unbridled nature of the LoC, those who are bound by duty to keep vigil at the treacherous forward posts prefer to keep their heads down. Any uncalculated move has the potential of getting punished by the enemy fire, especially on ranges where some posts are so close to one another that on a good day the foes get into a friendly banter.

However, since seasonal friends cannot be trusted, both sides traverse long backbreaking tracks from one post to another even if they are only a few metres away because these tracks have to be built as far away from the enemy observation posts as possible. Shelling is so commonplace that it ruffles no feathers among the security personnel posted along the LoC, unless of course, it causes serious damage, in terms of man or machine. On the contrary, it is the long silences that are causes for concern.

The evening of July 2 began with the routine shelling, but it yielded rich dividends for the Indian side. Shortly after 9 pm, the Pakistanis started firing on Indian positions in the Uri bowl. The firing, which included illumination shells used to assist infiltrators to cross the LoC on a dark night, continued for about two hours. After a break of a few hours, Indians responded with interest. A visibly beaming Indian brigadier said the next morning that accurate Indian artillery fire had set a Pakistani ammunition point and petrol, oil and lubricants dump in Chakoti across the Uri bowl on fire. That apart they had also inflicted some casualties, he said, expecting Pakistan to retaliate in the afternoon when the sun would be unhelpful to Indian observation for raining accurate counter-fire.

In accordance with the Simla agreement of 2 July 1972 the role of the UNCIP was declared defunct. India, however, allowed the military observers to remain in Srinagar, without legal validity or formal recognition

Though little has changed about the military held line, both sides have adjusted to the conditions that created this unusual feature in the first place. An exchange of telegrams between the two commanders- in-chief, India’s Sir Roy Bucher and Pakistan’s Sir Douglas Gracey, brought a cease-fire to the 14-month-long first war between India and Pakistan over Jammu and Kashmir on the midnight of 31 December/1January 1949. All military activities were frozen with the Indian and Pakistani forces holding positions as they were at that time. A 10-day conference at Karachi in July 1949 delineated the Cease-Fire Line (CFL), which ran from Manawar in the Punjab plains to Keran, North of Tithwal, whence it ran east of Chalunka. Within weeks, it was evident that Pakistan would not abide by the agreed conditions for the withdrawal of troops, and that the military observers under the United Nations Commission on India and Pakistan (UNCIP) would stay much longer than was envisaged. Ever since, the two warring states have often attempted to subtly change the CFL to their own advantage.

Pakistan undertook the misadventure in 1965. In a brilliant plan that was assiduously kept a secret until it unfolded, Pakistan commenced sending infiltrators (a mix of regular troops and militia) into J&K from August 2. As in the 1999 Kargil war, the Indian political and military leadership was caught napping. It was another matter that the people of J&K rebelled against the raiders. To support the falling infiltrators, Pakistan’s President Ayub Khan launched Operation Grand Slam, a massive attack, into the Chhamb sector on September 1, which led to the 22-day inconclusive war. A major gain for India was the capture of the Haji Pir Bulge, which was created by the 1949 cease-fire. The Haji Pir Bulge was the main route for infiltrators into the Valley in 1965, and is the shortest route between Uri and Poonch across the Pir Panjal range. However, under the Tashkent Agreement, the Indian leadership in a show of goodwill gave the Haji Pir Pass and the Bulge back, an operational blunder, which the Indian army regrets to this day.

The 1971 war was primarily about the creation of Bangladesh. In accordance with the Simla agreement of 2 July 1972, the CFL (after tactical adjustments which resulted from the cease-fire of 17 December 1971) was renamed as the LoC, and the role of the UNCIP was declared defunct. However, as a mark of respect for the UN, India allowed the military observers to remain in Srinagar, despite no legal validity or formal recognition. Unlike the two previous wars, which had J&K as the nucleus, the 1971 war saw less action in the troubled state. A notable gain for India was the capture of peaks in the Shyok valley and the Kargil sector. India’s 19 division in Baramullah successfully captured two tactically important features in the Lipa valley, between Tithwal and Uri sectors, and pushed its success further by wresting the Kaiyan bowl from Pakistan. From a viewpoint at India’s Tut Mari Gali (TMG) post, one gets a good view of the Lipa valley in the distance. In place of an underground Pakistani medical post in the Kaiyan bowl, at present, the Indian army has a full-fledged medical Field Surgical Section, which is the army’s only surgical unit in the area before flying a casualty to the corps hospital in Srinagar. Legend has it that as a young officer, Pakistan’s army chief, General Pervez Musharraf was treated at the Pakistani medical post in the Kaiyan bowl before its takeover by the Indian forces. In the mountainous sector of the LoC, the importance of the Lipa Valley for both India and Pakistan equals that of the Haji Pir pass alone. However, in the semi-mountainous and plains sector of the LoC, the problems and objectives are of a different kind.

At present, the 813-km-long LoC runs from a place called Sangam close to Chhamb in the south up to map grid reference point NJ 9842 in Ladakh in the north. On the ground, NJ 9842, lies beyond the Shyok valley and rests on the lower slopes of the Saltoro Range – an offshoot of the Karakoram Range. From NJ 9842, the line runs north and is called the Actual Ground Position Line (124 kms) where India and Pakistan have been locked in a glacier war since 13 April 1984. There is also a 265 kms International Border in Jammu division between Boundary Pillar 19 and Sangam, which was part of the erstwhile state of J&K. Pakistan does not recognise this IB and calls it the ‘working boundary,’ as it maintains that the border agreement was between Pakistan and the state of Jammu and Kashmir, not India. The LoC meanders through thickly vegetated plains and a semi-mountainous terrain in Jammu division, which is the responsibility of India’s 16 corps at Nagrota. North of Pir Panjal and upto the Zojila pass, the terrain is mountainous with the height of up to 11,000 feet (9,000 feet and above are referred to as high altitude areas), and is the responsibility of the Srinagar based 15 corps headquarters. Most of the high altitude areas start beyond the Zojila pass and are under the 14 corps, which was raised after the 1999 Kargil war with Pakistan.

Also Read:

The War Zone

Following up on the inaugural cover story of FORCE, here is another treasure from our archives. In November 2003, FORCE team spent a week in the Jammu division of Kashmir. Starting with the Rashtriya Rifles’ Delta force headquarters in the Doda sector of Jammu division to get first-hand experience of Indian Army’s counter-insurgency operations, the December 2003 cover story included interviews with chief minister J&K Mufti Mohammed Sayeed, chief secretary Sudhir Bloeria, Northern Army Commander Lt Gen. Hari Prasad, Director General, BSF Ajai Raj Sharma, Inspector General, BSF, Jammu division, Dilip Trivedi, Inspector General CRPF, Jammu Division, C. Balasubramaniam and countless unnamed officers from across the uniform. Field reporting at its best. Read on.

Given that the high altitude operations are a different ball game altogether, they are beyond the scope of this feature which focusses on the LoC as it runs through the 16 and 15 corps sectors – through Jammu division up to Zojila in the north. Given that the LoC is a multi-dimensional issue, to put it in the right perspective, we decided to divide it into three broad sections: operations, life, and the Military Civic Action (MCA) along the LoC.

Operations

The Indian army doctrine written by the Army Training Command in Simla in 1998 says, ‘On our western border (with Pakistan), a conventional conflict would probably be fought under conditions of near parity, both in quantitative and qualitative terms. However, we need to work out ways and means to change the ratio substantially in our favour; it is only then that a stalemate can be avoided.’ Given such a reality, the military aims at the operational level of war – which is a command in the case of a conventional war – in the J&K theatre would probably be twofold. One, to deny launch pads to the enemy and two, to capture maximum enemy territory. This means that at the tactical level, the aim would be to capture ground with a view to improve our defensive posture. Once such military aims are understood, the importance of the Lipa Valley and the Haji Pir pass in the 15 corps sector, and the Shakargarh bulge in the 16 corps sector becomes obvious. Though senior officers in the northern command do not explicitly say that the above would indeed be the command objectives in case of a war with Pakistan, they don’t deny that such an offensive thinking existed during the 10-month long Operation Parakram – the mobilisation of the army for war with Pakistan –, when, on two occasions, India was close to a war, and according to officers here, missed the third opportunity in October.

Legend has it that as a young officer, Pakistan’s army chief, General Pervez Musharraf was treated at the Pakistani medical post in the Kaiyan bowl before its takeover by the Indian forces in the 1971 Indo-Pak war. In the mountainous sector of the LoC, the importance of Lipa Valley for both India and Pakistan equals that of the Haji Pir pass alone

According to senior officers in the northern command, India’s best chance to spring a military surprise on Pakistan was in early January 2002. India’s mobilisation to support a limited war in J&K was complete, and Pakistani forces were yet not prepared to take on the beefed up Indian forces. Even as Pakistan’s Gen. Musharraf readied himself for the famous 12 January 2002 television speech, the Pakistan army in a show of desperation intensified firing all along the LoC. Such intensified firing is resorted to by Pakistan to elicit a similar response from India. The Pakistani media managers usually time the whole thing in such a fashion that media teams, both foreign and domestic, brought to the LoC usually get to observe the Indian counter-fire. In January 2002, however, the increased shelling by Pakistan on the LoC was to put the world on notice that a conventionally unprepared Pakistan could do the worst. Even as none in the northern command believed that Pakistan would resort to nuclear weapons, thanks to India’s dithering, Pakistan managed to ready itself for a limited war in J&K by March 2002. As is now well known, the second chance for India to fight a full scale conventional war with Pakistan came after the May 14 Kaluchak massacre. This time around, the war aims for the northern command were rather modest as the element of surprise had been lost.

According to officers here, by September 2002, Pakistan had started pulling back its 12 corps troops, which were brought into J&K from its western sector facing Afghanistan. There was trouble brewing along the Durand Line, and Pakistan had calculated that it was safe to pull back troops from its eastern front, as India was unlikely to start a war. Unknown to most in India, the northern command had made a strong case for a limited offensive to the government in October, days before India formally called off Operation Parakram. In short, the northern command was set for a limited campaign in January and October 2002.

A look at the Lipa Valley, with a local population of about 35,000 living in about 25 villages, from the TMG post underscores its importance. The Lipa Valley is surrounded by four mountain ranges – the Shamsabari, which runs from east to west and is six to seven kms from the LoC, the Kafir Khan, the Kasinag and the Chota Kasinag. The most important amongst these ranges is the Shamsabari, which slopes into the Valley on the other side. India dominates the Shamsabari range. If Pakistan manages to get a better foothold on the Shamsabari range, it would then be looking into the Valley from the top. This would help Pakistan to provide better support to infiltrators from this area. Moreover, once Pakistan obtains a firm lodgement on the Shamsabari range, its troops could easily roll into the Valley at a time of its own choosing in a war. The converse is also true. An occupation of the Lipa Valley by India would deny Pakistan a major tactical gain of using the Shamsabari range as a lodgement for sending its regular troops into the Valley, and of assisting infiltration.

At present, in the garb of a tourist spot, Lipa Valley, at an average height of 8,000 ft, is a prominent staging area for infiltrators. A recent report in the Pakistan magazine ‘Herald’ says that militants have started trickling in the Valley in small numbers to infiltrate into India before the onset of winter. The Herald correspondent spoke to one militant, Naimgul, who said that the Inter Services Intelligence has instructed them to merge with the local population in the villages so that they don’t look conspicuous. In his words, “The agency (the local name for ISI) has asked us not to keep more than three persons at a camp. It makes it more difficult for the American satellites to tell a home from a camp.” According to the report, currently, there are easily two-dozen such camps, each with the strength of about five. The Lashkar-e-Toiba, however, is maintaining close to 30 activists in its Khairatibagh camp in Lipa valley.

But Lipa valley’s strategic significance goes beyond it being a staging area for militants. Pakistan’s 75 Infantry Brigade Headquarters is also located in the Valley with its 19 Division based in Murree. Muzaffarabad, the capital of Pakistan occupied Kashmir, which is the centre of gravity of Pakistani forces in the theatre, and also the hub of terrorism into J&K, is 90 kms away. “We keep crying about the loss of the Haji Pir Pass as a case of spilt milk. But today, the strategic importance of Lipa Valley cannot be denied. We do have the Lipa Valley in mind,” said Lt Gen. V.G. Patankar, General Officer Commanding, 15 corps. What he did not say is that during Operation Parakram, two brigades worth of command reserve troops were exercising in that area. Haji Pir remains yet another command objective. Officers however concede, that unlike in the case of the 1965 war, it would be near impossible to wrest this from Pakistan.

In the 16 corps sector (the largest corps of the army), there are a number of operation level military objectives, from straightening the Shakargarh Bulge, to launch areas between Rajouri and Poonch. During Operation Parakram, an additional division- and-a-half and a corps headquarters were shifted here from the east against China. While the corps headquarters has gone back, there has been no dilution of the additional forces. Besides, the corps has armoured brigades as corps reserves, and certain battalions (which are involved in counter-insurgency operations during peacetime) were placed on the primary task on the LoC during the 10-month stand off with Pakistan.

A pecularity of this sector is the extreme forward defence operational stance adopted by both countries in the plains. This is based on built-up, heavily fortified linear obstacles called Ditch- Cum-Bundh (DCB) converted for defence with the home bank raised with concrete bunkers (there are much more steel permanent defences here than in 15 corps sector) and pill boxes and linked with a defensive minefield. The DCB has a continuous minefield along the far side to a depth of 1,000 to 2,000 metres. While in sensitive areas, twin obstacles of this nature have come up; minefields hug the home-side in other areas. Moreover, in places where there is long dry elephant grass, which can catch fire easily, the army has built anti-fire bundhs.

Moreover, the border outposts on both sides are reinforced to provide early warning. All appreciated approaches expected to provide a Black-Top road (tracks for corps logistics) on the home-side for a likely break-out have delaying/advanced positions turned into strong points. Beyond the minefield(s), a surveillance screen of small teams carrying automatic weapons and anti-tank rocket launchers has been established and machine guns nests are interspersed within the minefields. The bunkers are camouflaged and blend well with the DCB and are extremely difficult to spot.

In addition to providing opportunities for intense training, Operation Parakram helped the northern command in two other ways. First, surveillance equipment from abroad, which is needed for counterinfiltration operations, was procured in quick time. It was appreciated that in addition to fighting a conventional war, Pakistan would continue with infiltration of jehadis across the LoC. And second, sufficient funds for improving bunkers (called ‘works’ in army parlance) on the LoC were released by the government. The army carried on the twin job of improving bunkers and training for war simultaneously during Operation Parakram.

Amongst the surveillance equipments procured from France and Israel is the Hand Held Thermal Imagers (HHTI) that helps in observation up to two kms at night. These are still available in small numbers and have a need-based distribution rather than a uniform distribution. Ideally each post should have a HHTI, and if a post has more than one approach, then more HHTI should be made available. Next is the Hand Held Battle Field Surveillance Radars (HHBFSR). These are audio aids, which can help identify a man at a distance of up to six kms. This is, however, only possible if the soldier using this has enough experience and is able to distinguish between various cluttering noises.

There are also various short range Unattended Ground Sensors (UGS). The basic concept when using these sensors is that tactically important ground is held in strength. Since all ground, especially in mountains, cannot be physically held, the ensuring gaps are patrolled vigorously. Moreover, strong reserves are maintained at the brigade and battalion levels to react in case of enemy ingress. Some re-entrants, which are difficult to patrol but provide the enemy with attack-by-infiltration option, are provided with UGS. These are of various types. The seismic UGS have a range of up to 75 metres, the Infra Red UGS have a range of 50 metres, and there are secotic UGS in which a 500-metre wire is laid covering a likely enemy approach. When anyone steps on them, the indication is received at the controlling station. In addition, the artillery has the Thermal Imaging Integrated Observation Equipment (TIIOE), which includes a thermal imager, a laser range finder and a goniometer to find accurate range and bearing to the target. Many units on the LoC have also been provided with digital cameras.

The above devices have helped improve the density of surveillance and together with patrolling are force multipliers. Yet, according to a brigade commander on the LoC, “The surveillance equipment is partially effective because the technology does not cater for the lowest denomination of intelligence among men who operate these systems.” There is little gainsaying that with time the comfort level of jawans and even officers who handle this equipment would improve to derive maximum benefit from this technology.

“There is enough decentralisation of command, but only in self-defence,” said Lt. Gen. Hari Prasad. This means that formations have enough leeway to open fire in retaliation before informing the higher headquarters. However, care is taken to ensure that the firing is pinpoint and the tax-payers’ money is not wasted on aimless fire-assaults

Even as surveillance remains a manpower intensive effort, the northern command has started select fencing along the LoC. Said Lt. Gen. Hari Prasad, the northern army commander, “Fencing behind the LoC to check infiltration has started in both 15 and 16 corps. This would provide us with the second line of defence.” When asked if the infiltration has come down because of the above efforts, the army commander was emphatic in his response, “I do not think that infiltration has come down. We will have to wait till October (when snow begins to fall and most passes in the mountains close down) to see. However, our methods of interception have improved and this has put a lot of pressure on infiltrators.” Officers explained that the fencing was being done in two rings with the inner ring being electrified. While electrical fences may deter transgressors, they pose a risk to even our troops at night.

In the aftermath of Operation Parakram the Indian troops have started thinking in an offensive manner. This is evident in the way officers and jawans talk these days. Even as the primary task of the troops is to maintain the sanctity of the LoC, there is an eagerness to give an offensive punch to the enemy. This has been helped by the modernisation of infantry weapons and the employment of artillery in different ways. All infantry battalions on the LoC are equipped with Automatic Grenade Launchers, Under Barrel Grenade Launchers, Anti-Material Rifles, which have a 14.5 mm shell that can go through a normal bunker wall, and Konkurs Anti- Tank Guided Missiles with a range of 2.5 kms in mountains and 3.5 kms in plains. In addition, battalions have been provided with Medium Machine Guns with 1,500 metres range from old tanks, which are no longer in service.

Even as the firepower of a company locality has increased substantially, the artillery is regularly being used in a direct firing mode. This was quite unthinkable until the 1999 Kargil war when artillery was used for direct hits with good effect. During Operation Parakram, the 75/24 mountain guns, the 105 mm, the 130 mm, and even the 155mm Bofors guns were used in a direct fire mode at targets five to eight kms away. This, according to artillery officers at various forward posts, has instilled awe in the minds of the enemy. In terms of artillery, India has more firepower packed in its battalions than Pakistan. Consequently, this has enhanced domination of the LoC in terms of defeating conventional attacks.

Asked if there was a decentralisation of command as a consequence of Operation Parakram, Lt Gen. Hari Prasad, who took over the command on July 1, was a bit evasive. “There is enough decentralisation of command, but only in self-defence,” he said. This, according to officers, means that formations on the LoC have enough leeway to open salvos of fire in retaliation before informing the higher headquarters. Also evident is a cascading fire-effect, described by a young major as ‘chain-slapping.’ “The enemy hits me where I am vulnerable and I slap him back at a place where it hurts him the most,” he said. His words find a resonance in Lt. Gen. Patankar’s statement: “We do not initiate fire assault. But once the enemy starts we send fire back with interest. It is pinpoint, accurate firing. We don’t want to waste tax-payers money on aimless firing.”

Life on the LoC

The LoC is impartially unforgiving of troops and civilians alike. The diplomatic pendulum between India and Pakistan that periodically swings between war and peace has little impact on the lives of people living here. The conditions are so bad in some posts that the meals are cooked only twice a day – before sunrise and after sundown. Because any stray movement during the day is met with an enemy bullet. Said one Lt. Colonel, “We are so close to the enemy post that even a rifle bullet can kill.” One commanding officer’s cabin was in direct view of the Pak observation post. The glass panes of the cabin are riddled with bullet holes. After a narrow escape, a few months back, the CO finally got a huge concrete wall built just outside his cabin. “We cannot replace glass panes with concrete for the simple reason that it will block out the natural light and heat,” he explained. While the civilians, mostly nomadic shepherds, small farmers and daily wagers, carry on with the typical Indian fatalism – whatever will happen will happen – (lots keep happening, see box Chasing Life); the troops try to make the best of the bad situation.

Almost all posts have electricity, though the supply remains erratic. The troops, however, have their own generator sets to ensure power whenever it is needed. Since storing water is a problem in mountains, most forward posts have sintex tanks to store water.

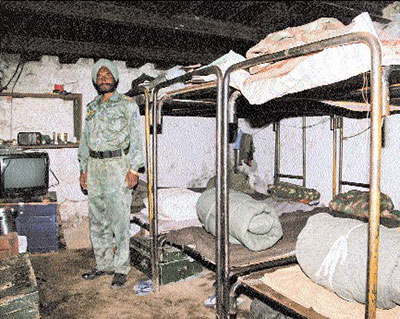

Basic amenities apart, all forward posts have television sets (often more than one with a reasonable collection of CDs procured from the bases) and are equipped with computers, some of which are connected by Local Area Network. This has facilitated the task of the commanders. Within minutes of an occurrence, such as, opening of enemy fire, the forward commanders send their Action Taken Report through the LAN in near real time to higher headquarters. But this is limited to only a few posts. Most of them use computers for data processing and entertainment. Many posts have digital cameras as well. And, officers apart, even jawans are quite proficient in their usage.

The living conditions of the jawans have improved as well though not very substantially. The sleeping bags have been replaced by bunk beds and even they have television sets of their own in their bunkers. While telephone communications have improved, the army still continues with the archaic ANPRC-25 radio sets of 60s vintage. With the inbuilt secrecy equipment, these radio sets’ range of 15 to 20 km have reduced substantially.

During Operation Parakram, the troops undertook a comprehensive review of ‘works.’ As against peacetime when a unit gets finances to improve about 50 bunkers in one season, during the 10-months warlike situation certain units got finances to build and improve up to 150 bunkers. On the LoC, the bunkers fall in three categories: Steel Permanent Defences (SPD) or fighting PD, ammunition PD, and self help bunkers made of sand and sometimes stones, if available. The ideal is to have the SPDs, but unfortunately not more than 50 per cent of these are available. Even those are not strong enough to take a direct medium artillery shell. But then, officers explain, getting a direct hit is a low probability. As a general rule, most bunkers, which are on the main enemy approaches, are SPDs. However, Lt. Gen. Patankar said that, “a rolling plan for five years which includes works, water and electricity to the posts on the LoC has been approved and its implementation would start soon.”

The government has recently sanctioned Rs 16,000 crores over a 10-year period for Habitat improvement of troops’ in peace areas. Lt Gen Patankar, however, said that Habitat improvement, implying better and permanent living structures, close to the LoC remains a problem area. Constructing temporary structures is not a problem as it can be done on leased land but making permanent infrastructures for troops involves clearances from various state government departments, which are not easy to come by. For example, the forest department objects to the felling of trees for building accommodation. “However, one area where we have received a lot of support is infrastructure building as it benefits everyone, the civilians, the state government, the paramilitary and the army. There are an increasing number of posts that are now connected by roads. Besides, the condition of existing roads has also improved tremendously,” said Lt. Gen. Patankar.

Almost all posts have electricity, though the supply remains erratic. The troops, however, have their own generator sets to ensure power whenever it is needed. Since storing water is a problem in mountains, most forward posts have sintex tanks to store water. Basic amenities apart, all forward posts have television sets (including the bunkers of the jawans) and are equipped with computers, some of which are connected by Local Area Network

The months between March and October witness maximum activities on the LoC, and they are not of the shelling kind only. The summer months are used for Annual Winter Stocking (AWS) to cater or the frosty months when snow and avalanches block a large number of forward posts, tracks and roads. There are posts on the LoC in the mountains that get buried under 15 feet of snow in winter. The battalion headquarters remain cut-off from such posts for about four to five months. It is an exacting task to keep the lines of communications open when snow plays havoc not only with the laid telephone lines but also road transport.

Only a few months ago, the army battalion near the Naugam village lost nearly half a dozen vehicles and a few men because of a sudden avalanche. The bodies of the dead soldiers could be retrieved only after a week as they were buried deep under the snow. Perhaps, it the nature of the job or the arrogance of the weather conditions that even the tragic looks comic.

One serving brigadier recounted an incident where they believed that four of their men had gone missing on a patrol. Actually the men had gone straight to their bunker without having dinner when the snow on top caused the roof to collapse. Fortunately, the roof fell in such a fashion that it created an air pocket through which the men were able to breathe. Once the snow cleared a bit, they started digging. It was then the rest realised that who they thought were missing or dead were actually right there under the snow. “It was not only a cause for celebration,” said the colonel, but, “also a laughing point for many days.”

During the present summer months, both mules (called Animal Transport) and local civilians are employed as porters to stock as much as 50 tonnes of foodstuff (dehydrated vegetables, which when soaked in hot water regain their original size and flavour, condensed milk, powdered eggs which transform into omelettes with the addition of boiling water and canned meat) and kerosene oil on these far away posts. Adequate ammunition stocking is a challenge, as there is a need to ensure that ammunition does not get wet in storage. Army’s AT companies have come from Simla and elsewhere to ensure that AWS is adequate and in good time. But taking the stocks to the posts has its own perils. The moment the Pakistani Observa-tion Post officer observes any such movement he starts shelling. One brigade commander recounted a recent incident when the enemy started firing on the AT convoy. The army lost quite a few mules.

This time is also used for general maintenance, upgradation and construction of bunkers, and improving the water and electricity situation, especially in the mountains. Even as both sides undertake their ‘works’, there is always a temptation to improve an existing bunker by making it bigger and stronger. This is enough reason for the other side to start artillery shelling to convey the message that additional fortifications on the LoC are unacceptable.

Military Civic Action

In the early years of militancy, the biggest nightmare for the army was the charge of high-handedness and human rights violation. The search and cordon operations became subjects of innumerable stories, some true and some partly true. This further alienated the people. In the last fews years, however, the army seems to have realised the importance of Winning the Hearts and Minds of the people. Sure enough the strategy is called WHAM under the military civic action of the armed forces, which entails providing the villagers with electricity and water in addition to medical facilities.

The army also runs a number of schools in these areas called Goodwill or Ujala schools. Where it does not have the required man-power or resources to run schools it sponsors the existing government ones by hiring teachers or providing bright students with scholarships. The military also organises recruitment rallies in these villages to encourage people to join the mainstream. Though the army and the BSF have been holding these rallies regularly, recently, even the air force had a grand recruitment rally in Srinagar. However, these recruitment drives have had a mixed response so far. Most of the villagers who are keen to join the forces get rejected on literacy and health grounds. In one such recent rally, the local officers collected a few men from the villages in their area overlooking a number of factors. But once these men reached the recruitment centre in Baramulla all of them were sent back.

“We have modified are standards to a certain extent to accommodate these people. But we can’t do more than that,” said one major. People in the areas bordering the LoC are largely semi-literate and even then they are only proficient in their local dialect or a little bit Urdu. And neither of them can get them a job. That apart, according to the officers who were involved in the recruitment rallies, most of the villagers suffer from some kind of ear infection, which disqualifies them. “This is the reason we are planning to hold a few health and basic literacy camps in these villages before the next rally,” said the major.

Though the army has an all-pervasive presence throughout the state of Jammu and Kashmir, the MCA programme is being largely implemented in the villages close to the Line of Control. Not only are these areas extremely remote with not even a semblance of state administration (one villager remarked, “We don’t even know who the local politician is. Some people came just before the elections but we have not seen any of their faces since), they also work as transit points for infiltrators before they move to the areas of their operations.

Said Lt. Gen. Patankar, “The MCA programme helps both. It is helping the poor, impoverished villagers as they have nowhere to go in their hour of need and it helps us in keeping a track of all activities that take place in these areas. Since the people are now convinced that the army is there for their good they are more comfortable in coming forward to report any unusual activity in their villages.”

The army has installed small boxes, a la, letterboxes, in select shops and schools so that people, including, children, can drop chits informing the forces, if they come to know of some militant-related activity in their vicinity. According to one colonel, more than the adults it is children who are keener to help the forces and get in the mainstream. “They have seen enough violence and poverty in their lives and now they want to change all that,” he said. This is the reason why the MCA programme is targetting the youth. It is believed that teenagers are going to act as catalysts to bring about a change in the attitude of the adults.

Irshad Ahmed is only 15 years old, but he is already aware of how different he is from the rest of his clan. Unlike other villagers in the Naugam district of Kashmir, bordering the LoC, he does not wear salwar- kameez. Dressed in a crisp cotton shirt, a pair of jeans and sneakers, he speaks with a smattering of English. He is in class 10th and wants to grow up to become an army officer. Perhaps, Irshad is exceptionally bright. But a huge credit for this transformation goes to the exposure he has had recently. He was part of the Bharat Darshan trip organised by the Army that took him to such places as Amritsar, Agra, Delhi and Jaipur. He also had an opportunity to meet President A.P.J. Abdul Kalam. “Kalam Sahab spoke with me,” he said with a touch of pride. “He asked me what I wanted to become and I told him that I want to be an army officer.”

The weather-beaten face of his grandfather contorted into a smirk. “What good was that trip? Did it get him a job? The army officer who had taken him should have got him a job instead of wasting so much time and money,” he snorted. But Irshad rudely cut him short, “The trip did me a lot of good. I had never gone out of my village before but now I have seen the Golden Temple, the Taj Mahal and the Rashtrapati Bhawan. And I want to study more before I start working.”

Irshad is not alone in his enthusiasm. Fifteen-year-old Kulsum Akhtar, who is preparing for class XI exams and was recently hired by the army to teach in a local school at the salary of Rs 1,500 is equally enthusiastic about improving the quality of her life. She walks for nearly half an hour to catch a bus, which takes her to Baramullah where she studies in a senior school. In a village where you can count the number of people who can write their name on one hand she dreamed of doing graduation. “Is it possible to get a job as a teacher in Delhi if you are a graduate?” she asked.

Statistically, these are only two cases. But between them they illustrate the winds of change, which are slowly blowing through these villages. Sure, the MCA programme has done a lot in offering people a hope for a different, and perhaps, a better life. Currently, the army is running three programmes through MCA. The biggest is Sadbhavna, which is run in association with the Central government. While the government provides the funds, the army executes the development programmes in remote areas of Jammu and Kashmir. The programme includes providing the border areas with electricity and water supply, primary health care and education. Occasionally, cultural events are organised so that a feeling of belonging is developed amongst the locals. In fact, at the Uri brigade headquarters, the army has opened a small heritage centre. The local people are encouraged to donate old photographs, pieces of traditional jewellery, handicrafts, hand tools etc. Said a brigadier, “Once upon a time, Uri used to be a flourishing town. However, ever since the raiders plundered it in 1947-48, the town never regained its glory. Till a few years ago people were scared of even acknowledging their past or their cultural richness. Now through the Sadbhavna project we are trying to restore some of that pride.”

One of the most popular programmes is Bharat Darshan, where children from border villages are taken on an all-India tour. Operation Maitree is part of this programme and involves bringing children from other parts of India to Kashmir. The idea is that this two-way communication would instill a sense of nationhood among the children of Kashmir. As an evidence of this sentiment one of the government schools has inscribed the following lines on its walls: “Kashmir Bharat Ka Taj Hai Aur Hame Is Pe Naaz Hai. (Kashmir is the crown of India and we are proud of it.)” The second programme is called the Border Area Development Programme, which is being run in association with the state government. Most of the villages close to the LoC are extremely remote and they have no infrastructure at all. The idea behind BADP is that once the army does the initial spadework as it has better access to these places given its counter-insurgency role, the various state agencies can take them over.

Ujala is the most recent programme that started only in 2002 at the initiative of the Lt. Gen. Patankar. The four-fold programme focusses on education, health care, cultural activities and cooperatives. This project is being run completely on the army’s initiative without any assistance from any government body. Lt. Gen. Patankar, through a number of presentations at the CII and FICCI, has managed to get funds and equipments for various projects under this scheme. For instance, the Usha Shriram group is running the Usha Sewing Centre. Aptech is running a computer centre. Besides this, various corporate houses have been encouraged to institute scholarships for bright students. Since most of the villagers are gujjars and draw their livelihood from cattle farming, efforts are being made to organise them into cooperatives so that not only do they earn better they also improve the quality of their produce.

The army has installed small boxes, a la, letterboxes, in select shops and schools so that people, including, children, can drop chits informing the forces, if they come to know of some militant-related activity in their vicinity. More than the adults it is children who are keener to help the forces and get in the mainstream. “They have seen enough violence and poverty in their lives and now they want to change all that,” said a colonel. This is the reason why the MCA programme is targetting the youth

Said Lt. Gen. Patankar, “Here the army acts as a catalyst by bringing different people together so that they can help one another. We don’t want the people to walk on our crutches forever. We want them to learn to walk on their own.” One of the reasons why the army efforts have been yielding positive results is the nature and the circumstances of these people. The villages close to the LoC are mainly populated by the gujjars who are very different from the Kashmiri people in the cities or the inner areas of Kashmir. They are illiterate with very little political awareness. Though Muslims, their religion is simplistic and heavily influenced by the sufi cult. It would be unfair to call them fence sitters, as that would imply a degree of craftiness. Compelled by their economic and geographical position, these people are simply opportunists. When the militants held sway in these areas they sang their tune. Now that the army dominates the entire region they are working with them.

In fact, the very presence of the army in the villages has opened employment opportunities for them. Men work as porters for the troops. The regular interaction has also given them the possibility of joining the forces. In fact, the rapport between the troops and the villagers is such that even small children stop and salute perfectly any passing military vehicle. From time to time, villagers, including women and children, hitchhike on the army vehicles. The fear and suspicion of the past has been replaced by a new confidence propelled by a consciousness of mutual requirement.

A short trip is enough to understand why Indian troops alone cannot stop infiltration along the LoC without support from Pakistan because the geographically irrational line works to its advantage. Even if the Indian army increases its numbers from the present strength it would still not be able to guard every inch of the ground. General Musharraf’s repeated claims that nothing is happening on the LoC are short on truth. The firing continues unabated, as does the infiltration of terrorists into Jammu and Kashmir.

It does not need a genius to say that infiltration is not possible without the full support of the Pakistan army. Leave alone crossing the LoC, the infiltrators would find it impossible to be anywhere close to the LoC if the Pakistan army did not want it. A case in point is the 22 May 2003 incident when one of the forward posts overlooking the Lipa valley noticed some infiltration at the height of nearly 12,000 feet. The troops engaged the militants and managed to kill all 12 of them. But once they went to retrieve the dead bodies, the Pak post started firing to prevent them from doing so.

Recalled the brigade commander, “When our troops engaged the infiltrators, one of them must have informed the Pak post, so they started firing to assist them. Obviously, they didn’t want us to retrieve the bodies because they would have been the irrefutable evidence.” The bodies, however, were retrieved after prolonged cross-firing.

Right now, both sides on the LoC are indulging in an offensive thinking, planning and execution. Given a certain amount of decentralisation of command, Indian commanders on the ground appear to be at liberty to give-it-back-to-the enemy before informing their higher ups. The question that elicited only meaningful smiles from the top brass of the northern command was: Is it possible for the army to start something on the LoC without clearance from the political leadership? Not a misadventure of the Kargil scale mounted by Pakistan, but our own mini- Kargils to improve the LoC to tactical advantage? The answer, as they say, is blowing in the winds.

Also Read:

Chasing Life

The message was cryptic, and serious enough to ruffle ordinary people. But the commanding officer at the sensitive Indian post at the height of nearly 10,000 feet had seen worse. One of the routine Pakistani shells had missed its target. Nothing unusual about it, except that it fell on a village house, seriously injuring four unsuspecting villagers: three adults and one boy.

Also Read:

Keep the Faith

It was a bunker with a difference. While bunkers at this forward post overlooking the Lipa Valley in Pakistan look nondescript, this one had a bright green roof, making it quite conspicuous. Laughed one army major, “We deliberately painted it green to mislead the Pak Observation Post officer. They think that it is a Pir Baba and wouldn’t dare fire.”