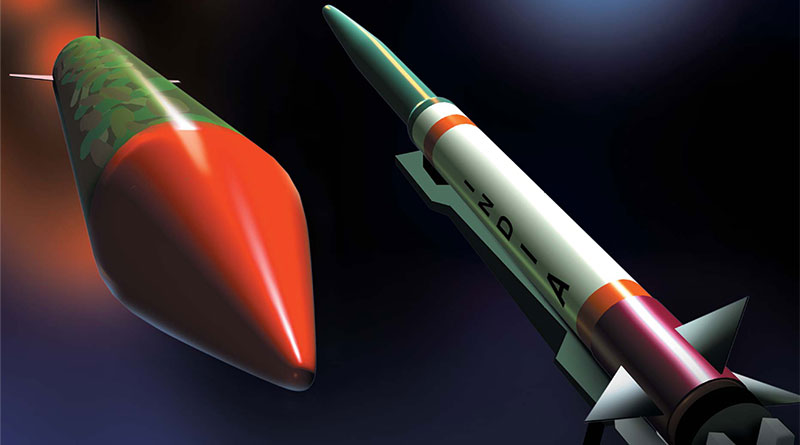

Countdown: Ballistic Missiles

Now that ASAT and ballistic missiles have been in the news, here is a nugget from the October 2003 issue of FORCE. As the saying goes, more things change, more they remain the same

Pakistan inches ahead with its ballistic missiles

Pravin Sawhney

The appearance of ballistic missiles in India and Pakistan is one of the most engaging stories of the last two decades. It is a story of lost opportunities, indecisiveness and inter-service wrangling which is the hallmark of India’s establishment. It is also a story of Pakistan army’s determination and its singular pursuit by whatever means to achieve missiles parity with India. This has led to the involvement of the US, Russia, China, North Korea, Israel amongst other nations, like Iran, into the region, thereby re-defining the region itself. India with a not-so-humble technology base embarked on an indigenous missile programme in 1983. Pakistan with little technological expertise decided to catch up in 1987. Throughout the Nineties, when Pakistan was clandestinely acquiring ballistic missile technology to undo India’s growing prowess, Pakistan repeatedly offered a zero-ballistic missile agreement to India. By the beginning of the millennium, Pakistan was talking of a ballistic missile stabilisation regime to ensure that both sides understood each other’s ballistic missiles. The US and Pakistan knew that not only had Pakistan caught up with India’s ballistic missile capability, but, Pakistan was leading India in certain aspects of ballistic missile acquisitions. Instead of talking ballistic missile issues with Pakistan, India has decided to ignore Islamabad’s suggestion, and instead seeks a similar dialogue with China, who refuses to sit on the ballistic missiles’ table with New Delhi.

India uses a strap down inertial navigation system (INS) for guidance, which is unsuitable for long range missiles. It is well established that beyond 2,000 km, a strap down INS cannot cater for the many inaccuracies which creep in because of extraneous atmospheric factors

Meanwhile, India’s defence minister, George Fernandes’ recent declaration about the induction of the indigenous surface to surface Agni and new variants of the Prithvi ballistic missiles into the services has thrown the armed forces into a tizzy, and can best be termed as pre-mature. In a written statement in Parliament on July 30, the minister announced that two variants of the Agni group of ballistic missiles, and the Indian Air Force and Navy version of the Prithvi missile were in the process of being inducted into the armed forces. The truth is that only half-hearted steps have been initiated. The actual induction of the weapon systems would not be possible until the government accords priority to the subject, which looks somewhat doubtful.

Also Read:

All the Prime Minister’s Men

Growing politicisation of defence institutions is a matter of concern

The Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS) has cleared the raising of two Agni missile groups, but financial sanction for the same is still awaited, which could take months, if not more. Until the financial clearance does not come, the army as the custodian of the Agni missiles can do very little. The Army Headquarters, however, have named the rocket groups as 334 Missile Group which will have the Agni-I missile, and the 335 Missile Group which would house the Agni-II missile. The Agni missile will be armed with nuclear weapons only. Manpower for these groups has been earmarked. The actual raising of these units is expected to begin near Secunderabad (to be close to Bharat Dynamics Limited, a public sector undertaking which was raised in 1970 and is responsible for the manufacture of all indigenous missiles) by the end of the year, by which time, it is hoped, that finances for the same would be released. The army, meanwhile, has decided to commence these raisings from its own financial resources, and not wait for the nod from the finance ministry, according to senior artillery officers.

The reason for this is that the army does not want to go the way of the Strategic Forces Command (SFC). The appointment of the Commander-in-Chief, SFC was announced by the government on 4 January 2003. Without wasting time, the Air Headquarters nominated Air Marshal T.M. Asthana as the first C-in-C, SFC. Unfortunately, the financial sanction for the SFC came seven months later in late July. This delay has resulted in the C-in-C, SFC sitting with a few staff officers at Air Headquarters with little to do. It is obvious that acquiring the land for the SFC site, and putting the infrastructure and manpower together (which will be a tri-service affair) will commence now, and would be a long affair.

The government, meanwhile, has also cleared the raising of two new Prithvi groups for the army. These will be called the 444 Missile Group and the 555 Missile Group and are expected to be fully operational by beginning 2005. The actual raising of these groups will start after the government allocates finances. The raising of the only 333 Missile Group, which has liquid propellant Prithvi is complete and the group, which is part of the newly raised 40 artillery division, has moved to its permanent location at Panchmarhi in Madhya Pradesh.

The Agni missile

The 334 Missile Group will have the Agni-I, which is a single-stage, solid propellant missile, which can carry a 1,000kg payload (the actual warhead would be about 700kg) to 700km. The missile was first test fired on 25 January 2002. According to sources, the firing was not perfect as there were problems with the re-entry vehicle separation from the booster rocket. The second test of the missile on 9 January 2003, however, was successful, after which the government took the decision to start a limited production of Agni-I.

The need for the Agni-I was felt during Operation Parakram, the 10-month-long military stand-off with Pakistan. Given Pakistan’s elongated geography, a majority within the military establishment led by the defence minister, George Fernandes, held the view that the 150km range Prithvi armed with a nuclear warhead, could hit most of Pakistan’s high value and strategic targets, which are close to the border, should the need arise. Hence, the Agni missile, costing nearly Rupees 400 million each would not be cost-effective against Pakistan. Yet, it was argued that a new cost-effective missile meant exclusively for the nuclear role was required. This was needed to make the undeclared distinction that the Prithvi would be used with conventional warheads only. Considering that the Agni-II had already been test-fired successfully, it was not difficult to make the Agni-I.

The Army Headquarters have named the rocket groups as 334 Missile Group which will have the Agni-I missile, and the 335 Missile Group which would house the Agni-II missile

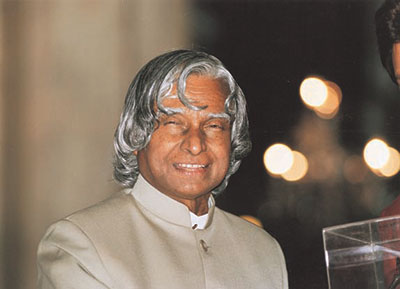

The Agni-II came into being after the 1998 nuclear tests, when India acknowledged that the Agni was indeed an IRBM and not a ‘technology demonstrator’, and that it would be nonsensical to employ an expensive weapon system with a conventional warhead to knock-off a few buildings thousands of kilometers away. The Agni-II was successfully test-fired on 11 April 1999, and again on 17 January 2001. The ballistic missile is a two-stage solid propellant (Hydroxyl-Terminated-Polybutadiene) rocket motor with a strapdown-Inertial Navigation System and has achieved a range of 2,000km carrying a 1,000kg warhead. After the first test of the Agni-II, the then DRDO chief, Dr APJ Abdul Kalam had said that Agni-II would be both road and rail mobile with a modular fuel configuration. The decision to start a limited production of Agni-II was taken in May 2001. The then Foreign and Defence minister Jaswant Singh told a meeting of the Defence Consultative Committee on 31 May 2001 that a limited serial production of Agni-II had begun, and the IRBM would enter service in 2001-2002.

After an intense inter-service wrangling between the army and the air force, the government finally decided in July 2001 to give the Agni to the army. The air force, since the Nineties, had argued that it alone was best suited to fully exploit strategic weapons like the Agni. It suggested the creation of a ‘Strategic Aerospace Command’ to bring all air, space and strategic assets under one umbrella. The army, sensing that unlike the other two services it would be left without nuclear weapons, sought possession of the Agni in January 2001 on the plea that all surface-to-surface weapons should remain with the ground forces. The then defence minister, Jaswant Singh’s reason for giving the Agni to the army was that the weapon is a land-based deterrent and only the army has the logistical strength to handle India’s sole nuclear tipped missile. Moreover, as the army alone has established procedures with the ministry of railways for movement of trains carrying troops in war and for exercises, it is best suited to retain the Agni. Further, a need for greater manpower to keep the missile safe from terrorist attacks during rail movement clinched the missile ownership in favour of the army.

The artillery, however, as the user of the weapon system, is of the opinion that Agni-II should be road mobile with solid propellant only. It is still not clear whether the 335 Missile Group would get the two-stage solid propellant Agni-II, or the earlier Agni-II model which has a two-stage solid-liquid propellant, the first stage being the solid propellant Space Launch Vehicle -3 and the second stage consisting of the liquid propellant Prithvi. The reason for this is that while the artillery prefers the complete solid propellant Agni-II, the other version of the missile which has a lesser range is lighter. This enhances the road mobility of the missile.

The Agni Missile Group will comprise four mobile launchers, each being capable of an autonomous employment. Senior officers in the artillery opine that four numbers of Agni-I with nuclear warheads would effectively cover the area of, say, the entire army’s western command, which stretches from the south of Jammu to northern Rajasthan.

According to top sources, while India has no plans to make intercontinental ballistic missiles, preparations are afoot to test fire the Agni-III with a possible new configuration to achieve a range of 3,000km with a 1,000kg payload. Scientists are understood to be working on two possible modification options for Agni-III. One option is to develop an additional solid booster with more propellant. The second option is to add a third stage to the existing Agni-II. Scientists concede that stage separation is a complex business and would require more flight tests. The Agni-III test-firing is slated for the end of the year. An issue which is of greater import is the need for an INS. India uses a strap down inertial navigation system (INS) for guidance, which is unsuitable for long range missiles. It is well established that beyond 2,000km, a strap down INS cannot cater for the many inaccuracies which creep in because of extraneous atmospheric factors. According to sources, INS technology acquisition from outside is a high priority. Work on the Agni-III and an INS is continuing simultaneously.

The Prithvi missile

The 333 Missile Group which has the 150km range battlefield support Prithvi capable of carrying a 1,000kg payload is part of the 40 artillery division. The missile group has two sub-groups, each divided into two troops with two launchers each. The sub-groups are self-contained for independent deployment. When deployed over a frontage of 100 to 150km, the missile group can, if required, concentrate on one target. The Prithvi, armed with conventional warheads, is well-suited for tasks in depth. For example, it would be utilised for battefield interdiction in depth in conjuction with the air force. The Prithvi would be the primary means of degrading enemy theatre and strategic reserves before they are effective in the tactical battle area. The missile would also be used to facilitate counter air operations by neutralising enemy air fields, disrupt military communications by causing damage to railway marshalling yards, and to deny use of naval dockyards and harbours. However, according to artillery officers, a first strike option by Prithvi would merit the following considerations: a need to appreciate the overall operational situation; the likely enemy reaction; the likely reaction of the international community; and whether employment dividends outweigh deterrent dividends. For these reasons, the employment of the Prithvi would initially be controlled by the Army Headquarters. At a later stage, the control could be delegated to lower formations like command and corps headquarters.

The Prithvi has two limitations. One, the missile has never been fired to its mean fighting range on a land target. The only ranges available are in the Rajasthan desert and their use is politically unacceptable because of the proximity to Pakistan. The accuracy of the missile has only been assessed from pre-surveyed and prepared technical sites. Various claims have been made about Prithvi’s accuracy. The Prithvi project director, Dr V.K. Saraswat has given the accuracy as 25m CEP (Circular Error Probability), where CEP is the measure of accuracy implying that 50 per cent of rounds fired would fall within the given radius from the target. Because the Prithvi lacks a proven terminal guidance system, according to the army, a realistic estimate of Prithvi’s CEP is 0.01 percent — at the maximum range of 150km, 82 per cent of rounds will fall within a radius of 150m. Besides the High Explosive monolith warheads, the Prithvi has bomblet sub-munitions. The DRDO has yet to develop the incendiary warheads and blast-cum-earth shock sub-munitions for the missile. While fuel-air explosives can also be employed with Prithvi, the government has not cleared their use.

The High Explosive (HE) monolith, unfortunately, will have little penetration given its fragile nose-cone. The warhead will be effective for use in built-up areas, but will not be cost-effective against hardened field fortifications. The 800-1,000 kg pre-fragmented warhead has greater potential for use against exposed ‘soft’ targets, but a large number of artillery officers opine that in a Tactical Battle Area, the indigenous Pinaka Multi-Barrel-Rocket-Launcher (MBRL) and the soon-to-be-acquired Russian Smerch will be more effective.

The irony, however, is that six years after the raising of the 333 Missile Group, the government has yet not issued a clear directive on how the group would be tasked – for a tactical or a strategic role, or both. This question eludes the artillery

The other limitation of the Prithvi is its liquid propellant. At a time when most ballistic missiles in the world use solid propellants, Prithvi’s liquid propellant — minimum 50 per cent isomeric xylidiene and 25 percent di- and tri-ethylamine and red fuming nitric acid as oxidizer — has large specific impulse and can deliver greater payloads to longer distances. But liquid propellants are difficult to handle in the field and during tactical movements. The apparent drawback of handling liquid propellant in the field is sought to be partly overcome by additional training. Topping of each launcher at the operational site takes about 20 minutes, and the entire operation, from receiving orders to firing a missile group, is about two hours. However, pre-filled missiles will be preferred for certain employments. An accompanying problem with liquid propellant is their long logistics train, which provides an easy target for enemy counter-fire. If the DRDO were to provide Prithvi with solid propellants, the existing 24 numbers of various types of vehicles needed for fuel topping in the field could be reduced to a mere six.

In short, the battlefield support Prithvi missile needs an assured accuracy with conventional warheads, and there is a need to replace the liquid propellant with a solid one. This, however, will not happen soon. Even as the 333 Missile Group is operational, the soon-to-be raised two missile groups will also have liquid propellants. The army has accepted the DRDO prioritisation that work on the solid propellant Prithvi missile would have to wait until 2005. “The solid propellant Prithvi will be a new design, and the DRDO does not want to get into it now,” said a serving general.

There is intense speculation both in the domestic and foreign media regarding the number of missiles with each Prithvi missile group. While this figure is classified, a reasonable answer would be 80 missiles per Prithvi Missile Group. The first-line ammunition, which a unit carries on its weapon system, in the case of the Prithvi unit is likely to be four missiles each on eight launchers. The second-line ammunition is also likely to be four missiles per launchers, and the reserves could be two missiles each per launcher. It is reasonable to assume that Bharat Dynamics Limited would have so far produced more than 80 Prithvis. The excess numbers would help the raising of the new missile groups.

Another issue which is exercising commanders is whether to use the Prithvi with conventional warheads alone. Opinion is divided over this subject. Most argue that no limitations should be put on the weapon system. Its employment would be dictated by the progress of war, and the changing appreciation of various military thresholds. It is felt that Pakistan, like India, will not use nuclear weapons early in a war, and would read the developing war as carefully. Both sides are also likely to send enough warning signals and indicators before crossing the nuclear threshold. The contrary argument is that in the din of the war, the chances of misreading a ballistic missile warhead cannot be ruled out. “Considering that the government has cleared the raising of two more battlefield support Prithvi groups, the missile, in the final analysis, will be used with conventional warheads only. Otherwise, what is the need for new raisings?” asked a senior artillery officer. The irony, however, is that six years after the raising of the 333 Missile Group had commenced, the government has yet not issued a clear directive on how the group would be tasked — for a tactical or a strategic role, or both. If both, at what stage would a nuclear warhead be married with the missile, and by whom, are questions which elude the artillery.

The Indian Air Force, on the other hand, wants to use its missile variant — 750kg payload (the warhead would be no more than 500kg) to a range of 250 km — for interdiction purposes, but the high cost, low delivery content, and a possibility of collateral damage, considering the missile is not so accurate, will limit target options. Unlike the army, the air force had made a strong case for solid propellant Prithvi on grounds that its 500kg warhead weight precludes usage of a nuclear warhead. However, it seems that the service would have to contend with a liquid propellant Prithvi.

The naval Prithvi is the air force version made suitable for firing from a surface ship. The naval Prithvi’s suggested range of 350km is incorrect, as this version will carry a 750kg payload to only 250km. In effect, the Prithvi with the army and the other two services are the same, with the trade-off done between the payload and the range. According to sources, while a ship-borne Prithvi will increase the missile range artificially, it would make the ship vulnerable to enemy counter-fire, and also eat into the space available on the ship. Given that the land-based version can hit almost all valuable targets in Pakistan the naval version is unlikely to be used. It appears more to be a case of a service’ prestige as the navy did not want to be left out. Moreover, the distribution of a single weapon system — Prithvi — with the three services is an unnecessary strain on maintenance.

Pakistan’s ballistic missile prowess is credible. And India knows this. Contrary to India’s claim, Pakistan successfully coerced India to not launch a military offensive in May and October 2002 by firing a series of ballistic missiles on both occasions

Pakistan leads India

For the first time on 17 February 2001, Pakistan did not respond to India’s firing of its Agni-II ballistic missile. On all previous occasions, every ballistic missile fired by India was countered with taller claims by Pakistan. On this occasion, Pakistan’s ruler, Gen. Pervez Musharraf brushed aside a need for replying to India’s test by one of their own, and also spoke about the futility of a ballistic missiles race. He said, “Pakistan would not try to match India in respect of the number of missiles produced, but would retain just enough missile capacity to reach anywhere in India and destroy a few cities, if required.” Even as his statement is not sacrosanct, it does show the ballistic missile roadmap that the Pakistan army, as the sole custodian of ballistic missiles, has in mind.

First and foremost, Pakistan’s ballistic missile prowess is credible. And India knows this. Contrary to India’s claim, Pakistan successfully coerced India to not launch a military offensive in May and October 2002. It is well-known that during Operation Parakram, India was twice ready, in January and May 2002, to hit Pakistan, and the Indian northern command had made a strong case to attack Pakistan in PoK to New Delhi (September cover story of FORCE), which both the US and Pakistan knew. By firing a series of ballistic missiles in May and October 2002, Pakistan had sent a strong and credible warning to India to desist from starting a war, and had succeeded. On the first occasion, Pakistan fired its long range Ghauri-I or Hatf-V, Ghaznavi or Hatf-III, and Abdali or Hatf-II missiles. On the second occasion, it fired Shaheen-I or Hatf-IV missile with a range of 700km and a 1,000kg payload twice. Considering that the US and other western powers had issued advisory warnings to their citizens to leave India and Pakistan ahead of a likely war, it was Pakistan’s ballistic missile warning that sobered the Indian leadership.

Pakistan’s moves to acquire ballistic missiles have been done to a well drawn purpose. There was a need to counter the manufacturing capability of India’s Prithvi. The importance of India’s indigenous Prithvi was that if produced in large numbers it could tilt the conventional arms balance between India and Pakistan decisively in favour of India. This would have had a detrimental effect on Pakistan’s Kashmir policy by restricting its military options. Also required were a few numbers of long-range ballistic missiles capable of hitting deep inside India for strategic purposes. Thus, it was not enough to have a few Chinese M-11s (renamed Hatf-III or Ghaznavi), but its manufacturing capability was needed to match the Prithvi. However, it was not necessary to invest in manufacturing North Korean No-Dong missiles (renamed the Ghauri series), but a few numbers with nuclear warheads were felt enough for deterrence purposes. It was, however, emphasised that the best be acquired and improved to more than match India’s missile arsenal.

Taking a cue from China, Pakistan is likely to use its ballistic missiles with conventional warheads in support of its air force, and to overcome its shortcomings in land-based firepower. It would be instructive to study the PLA’s changed thinking on ballistic missiles

Pakistan’s acquisition of ballistic missiles has been well-documented by the US intelligence agencies. To recapitulate the highpoints, Pakistan surprised the world in 1989 by announcing a sudden break-through in making ballistic missiles. Its army chief, Gen Mirza Aslam Beg, said that Pakistan had successfully tested indigenous Hatf-I and Hatf-II missiles with a range of 80 and 100km respectively with a payload of 500kg. He added that Pakistan was developing the Hatf-III missile in collaboration with ‘our friendly country’, a phrase which he used to designate China. What Beg did not admit was that the Hatf-III project had faltered, otherwise why would Pakistan seek the M-11s from China? Between 1991 and 1994, nearly 84 M-11 missiles were transferred from China to Pakistan and stored at the Central Ordnance Depot at Sarghoda.

Pakistan kept the M-11s in crates until 1996 and made a virtue out of necessity. This put the onus of starting a so-called missile race in South Asia on India, thereby compelling the US to exert enormous pressure on India to go slow with its indigenous Prithvi and Agni programmes, which India did. Pakistan, meanwhile, had acquired the manufacturing capability of M-11, mobile, solid propellant with a 300km range and a 500kg warhead, by 1997. The missile production unit with Chinese help was set up at Fateh Jung under the aegis of National Development Complex. Also commissioned in 1997 was the solid fuel plant to manufacture all key solid fuel ingredients. Once Pakistan got the M-11 manufacturing capability to match India’s Prithvi production by the middle of 1997, M-11s, now called Hatf-III were operationalised with induction into the 155 Composite Rocket Regiment of Second Army Arty Div., Attock.

Alongside, with China’s approval, Pakistan established contacts with North Korea in 1993 to buy its ballistic missiles. Beginning 1998, North Korea transferred about 12 liquid-fueled, mobile No-Dong missiles to Pakistan. Pakistan’s Ghauri or Hatf-V missile with a range of 1,000km carrying a 600kg warhead fired on 6 April 1998 is the North Korean No-Dong missile. Pakistan’s claimed indigenous Ghauri-II or Hatf-VI missile with a range of 1,500km and a 700kg warhead fired on 14 April 1999 in reply to India’s Agni-II fired on April 11 was again the North Korean improved No-Dong missile. It is known that North Korean missile designers and engineers have travelled to China for professional training and technology exchanges since early 1990s.

Meanwhile, in line with the philosophy of improving existing missiles, which coincided with the internal power tussle between two top Pakistani scientist, Dr A.Q. Khan of the Khan Research Laboratories and Dr Samar Mubarakmand of the National Development Complex, Pakistan embarked upon the goal of eventually having a few long range missiles with solid propellant and better guidance and control systems. The Khan labs are responsible for acquiring and improving the liquid-propellant Ghauri series, or the No-Dong missiles. Dr Mubarakmand has been tasked to work on the solid-propellant Shaheen series with Chinese help. The need for twin channel arose because the US kept a close watch on Chinese proliferation activities after the latter in 1996 relented to abide by Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) provisions. Shaheen-I, also called Hatf-IV, with a 700km range and a 1,000kg warhead was fired on 15 April 1999. Pakistan announced the induction of Shaheen-I in its army in March 2002, and Ghauri-I in January 2003.

Even as the Indian government is debating the future of Agni, the Commander-in-Chief, Strategic Forces Command has been asking a number of questions from the National Security Advisor. It is unlikely that he will get any answers in a hurry

Hence it is safe to draw the following inferences:

- Unlike the Indian military, the Pakistan Army is in full control of its ballistic missile programme; the limited assets have not been divided within the three services.

- Pakistan has inducted its Hatf-I, Hatf-II, Hatf-III, Shaheen-I and Ghauri-I into the army. India, on the other hand, has only the battlefield support Prithvi missile in service.

- Pakistan would have acquired better missile guidance systems from China. It would not be a surprise if Beijing would have given the INS for Pakistan’s Ghauri missile.

- Taking a cue from China, Pakistan is likely to use its ballistic missiles with conventional warheads, both liberally and aggressively in support of its air force, and to overcome its shortcomings in land-based firepower. It would be instructive to study the PLA’s changed thinking on ballistic missiles (see box)

- The Ghauri-I has had a total of three test-flights, one done by North Korea on its No Dong-I and the other two by Pakistan itself. Given a proven guidance system, the Ghauri is credible for strategic targetting.

- Unlike the Indian defence services, the Pakistan Army fully knows its nuclear and missile capabilities and controls them.

- And, unlike India which would depend on its aircraft for delivery of nuclear weapons, Pakistan’s preferred nuclear delivery system will be its unstoppable long range ballistic missiles, the Ghauri and Shaheen series, in addition to the aircraft.

Meanwhile, even as the Indian government is debating the future of Agni, the C-in-C, SFC has been asking a number of questions from the National Security Advisor. Key amongst them are: What is the minimum command and control system to ensure no premature activity? At what point should the Agni IRBM be integrated, deployed and made ready for firing? Who will integrate the warhead/re-entry vehicle and ensure that the complete system is in a position for accurate launch? What will be the surveillance and target acquisition facilities? Who will set up a target priority list, and, with whose assistance? It is unlikely that he will get any answers in a hurry.

Also Read:

Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Ballistic Missiles

There are two types of surface-to-surface missiles: ballistic and cruise.

Also Read:

Ballistic Missiles: India vs Pakistan

Ship-Launched Ballistic Missiles

The development of Dhanush by the DRDO is a part of its ongoing Sagarika programme, which is a quest for sea-launched ballistic missiles.

PLA’s Conventionally Armed Ballistic Missiles

China, in the Eighties, made two significant breakthroughs regarding ballistic missiles.

North Korean Ballistic Missiles

While North Korea started an aggressive ballistic missile programme in the late Seventies, what is of interest to us is the No-Dong ballistic missile series which commenced in 1988.