Militarisation of the deep seas was inevitable, but efforts must be made to protect the marine environment

Shrikumar Sangiah

Shrikumar Sangiah

The world is steadily moving away from fossil fuels towards more sustainable solutions to meet its energy needs. This has led to an increase in the demand for rare earth elements (REEs). REEs are critical for the manufacture of batteries and electric vehicles. This shift towards sustainable sources of energy comes with serious security implications arising from China’s disproportionately large hold on the REE industry. The majority of the world’s REE reserves are found in China—making the world heavily reliant on China for its REE needs.

Many key defence equipment rely on parts made from REEs. REEs are essential for the manufacture of GPS equipment, cell phones, fibre optics, computers and missiles. Rare earth elements yttrium and terbium are used for laser targeting and weapons mounted on combat vehicles. According to a 2013 United States Congressional Research Service report, 920 pounds of REEs are used on each F-35 Lightning II aircraft.

China already dominates the land-based global supply chains of REEs and is now rapidly expanding its presence in deep-sea mining (DSM), accentuating existing energy and military security concerns. Until very recently, 70 per cent of all the cobalt (a key ingredient in the manufacture of Li-ion batteries) used worldwide was sourced from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Chinese companies own 15 of DRC’s 19 cobalt mines. Almost all the cobalt from DRC’s mines is shipped to China to be refined before it is sold in the world’s markets. The DRC is losing jobs and its fair share of the profits while China has gained a stranglehold on the world’s cobalt supply chain.

Recently, a Congolese court barred a Chinese firm from operating one of the cobalt mines, for cheating on royalty payments. There has also been growing public resentment, in the DRC, against the loss of jobs and the flight of profits to China. Increasing difficulty in sourcing REEs from overseas mines has fuelled China’s concerted push in DSM to maintain its dominance in the REEs market.

Greater investments in DSM further key strategic objectives for China. It helps solidify the world’s dependence on China for REE supply. Control of the supply of REEs hands China the leverage over the world’s ability to manufacture EV batteries, solar panels, semiconductor chips and guided missiles—potentially providing China with an enormous strategic advantage over its adversaries.

The Deep Sea

The deep seas, once considered the last frontier of exploration, have increasingly become the focus of militarisation efforts by nations across the globe. The concept of militarising the deep seas traces back to the emergence of naval power in ancient civilisations. From the Phoenicians to the Greeks, and Romans, maritime dominance played a pivotal role in the expansion of territory and shaping of the course of history. However, it wasn’t until the 20th century that advancements in technology enabled nations to explore and exploit the depths of the oceans for strategic and military purposes.

Deep sea militarisation efforts are driven by a combination of strategic imperatives, economic interests and territorial disputes. The United States remains at the forefront of deep-sea military operations, boasting a formidable fleet of nuclear-powered submarines and underwater surveillance platforms.

China has emerged as a major player in the militarisation of the deep seas, rapidly expanding its submarine fleet and investing in advanced undersea warfare capabilities. The South China Sea, home to valuable natural resources and hotly contested territorial claims, has become a focal point of maritime tensions, with China asserting its sovereignty through the construction of artificial islands and the large-scale deployment of naval assets.

Russia continues to maintain robust underwater warfare capabilities. It uses its vast Arctic coastline to project power in the polar regions and secure access to critical sea lanes. The Arctic, rich in untapped energy resources and possessing immense strategic significance, has become an arena for geopolitical competition, with Russia asserting its dominance through military deployments and infrastructure development.

Other nations, including France, the United Kingdom, India and Japan have also invested in deep sea militarisation to safeguard their maritime interests and protect vital sea lines of communication.

Technologies for the Deep Seas

It is estimated that, globally, only about 10 per cent of the ocean floor has been mapped. Despite this, the leading navies are committing significant investments to develop technologies for use on the seabed. Advancements in technology have revolutionised deep sea militarisation, enabling nations to conduct stealthy underwater operations and gather intelligence in hostile environments.

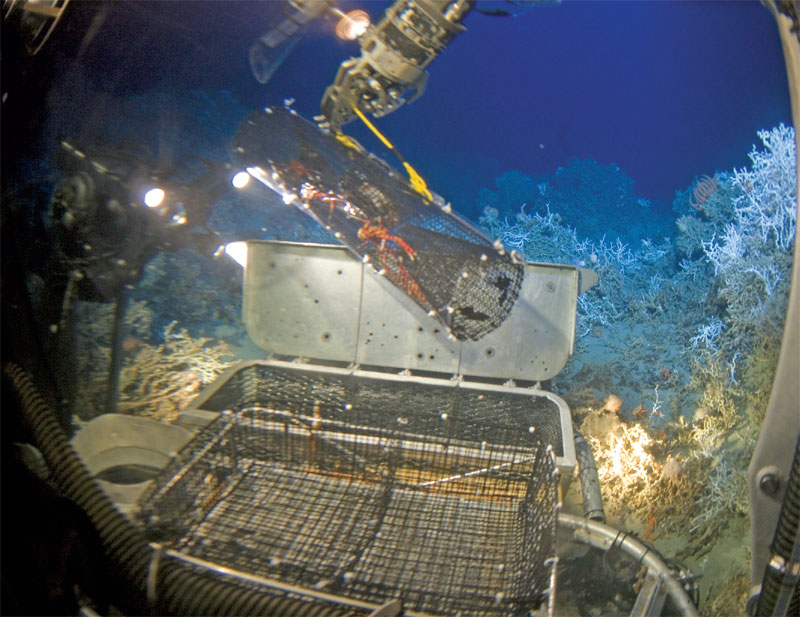

The proliferation of unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) has expanded the capabilities of naval forces, allowing for covert surveillance, mine countermeasures and underwater reconnaissance missions.

Unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs), besides their use for military applications, are increasingly becoming key tools for scientific research, maritime defence and commercial development of underwater resources. Increased automation of UUVs is also helping reduce costs. UUVs are being deployed in areas requiring continuous intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR). UUVs are especially effective in areas where access is denied or where ISR activities necessarily need to be clandestine.

The leading navies are also investing heavily in the development and construction of AUVs. AUVs can undertake dual-purpose, long-range ISR and mineral exploration missions. Such AUVs can be used to survey the ocean depths for enemy submarines, act as launchpads for UUVs and act as platforms for the deployment of underwater weapons.

China has made impressive strides in the construction and deployment of several deep-sea submersibles. The Haiyi, an underwater glider reached 6329 metres, Jiaolong dived to a depth of 7062 metres and the unmanned submersible Haidou reached 10,088 metres.

Furthermore, advancements in sensor technology, including in sonar systems and hydrophones, have enhanced the ability to detect and track submerged targets with unprecedented accuracy. This, in turn, has spurred the development of anti-submarine warfare (ASW) strategies and countermeasures aimed at neutralising potential threats lurking beneath the waves.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning algorithms in underwater surveillance systems is set to enhance the speed and accuracy of data analysis, enabling the world’s navies to identify and respond to emerging threats in real-time. Autonomous underwater platforms equipped with AI-driven decision-making capabilities could revolutionise naval warfare by augmenting human decision-making and adapting to dynamic operational environments.

You must be logged in to view this content.