AUKUS will not undermine QUAD; might even benefit India

Col Ajay Singh (retd)

Col Ajay Singh (retd)

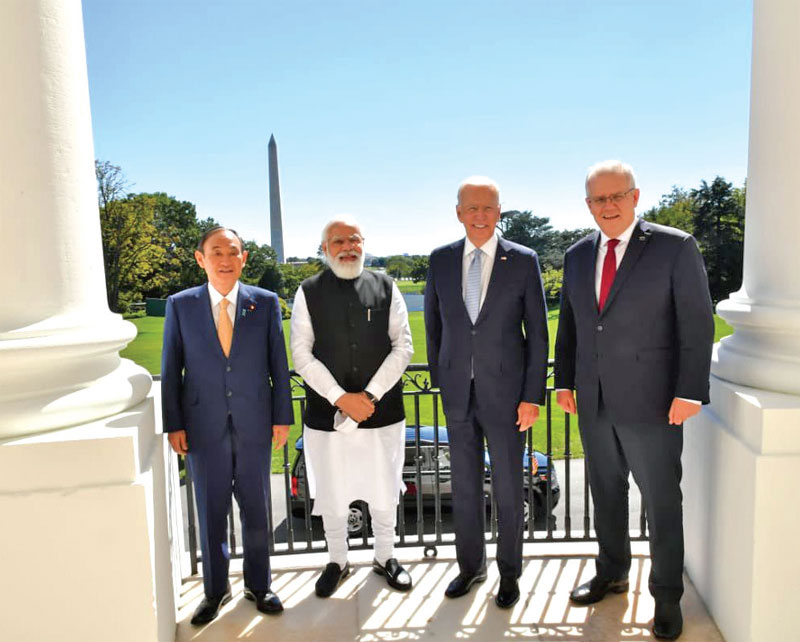

The most significant aspect of the Quad summit hosted by President Joe Biden in Washington this September was that it was held so soon after the virtual meeting of heads of states in March. It heralded one thing—Quad seems to be here to stay. Coming in the backdrop of the Afghanistan debacle, and the ripples caused by AUKUS, it is a message that the focus has indeed shifted to the Indo-Pacific, where this grouping hopes to counter an increasingly belligerent China.

Unfortunately, this meeting too, did not formalise the alliance, nor did it lay out a definite charter—less the fact that foreign ministers would meet once a year. But the meeting did highlight the concerns of the four members that ‘our shared futures will be written on the Indo-Pacific.’ And this grouping would help provide a balance in the region against an increasingly assertive China, and perhaps provide a security umbrella without overtly military overtones.

In the vision for ‘shared prosperity in the Indo-Pacific’ the Quad summit rolled out three C’s—Covid, critical technologies and climate change. The fourth ‘C’—China—was not mentioned. But it was the elephant in the room. What that implies is that the grouping aims to synergise the economic, ideological and technological clout of its members to provide a cohesive alternative to China.

The roll-out of 1.2 billion doses of vaccine for the region—in which the Indian Biological E will manufacture the Johnson and Johnson vaccine, whose technology will be supplied by the US; the financing by Japan and the delivery logistics by Australia is just one of the ways in which we can move together. The first attempt had been unfortunately stymied when India had been unable to export the vaccines because of the debilitating second wave—but now seems back on course. Even more important than the vaccine rollout was the convergence on critical technologies to ‘create resilient and dependable supply chains.’ This will move supply chains in critical fields like semi-conductors and telecom away from China. It would also help develop Open Radio Access Network (O-RAN) for secure 5G networks. This will provide a 5G alternative to Chinese companies such as Huawei and Tencent, whose predatory snooping could be a severe security risk for the host nations.

This could be a massive opportunity for India. We have the manpower and intellectual capability for chip manufacturing, but not the manufacturing wherewithal. Pooling in the technological know-how and manufacturing capability from Japan and USA could enable us to become the hub of this vital component.

Other initiatives such as the development of the Blue Economy of the region through infra connectivity, cyber and maritime security are also on the anvil. And Joe Biden’s pet project—the B3W—Build Back Better World Proposal offers an infrastructural alternative to China’s BRI which can wean smaller nations away from its financial embrace.

There was no mention of any security or military aspects (not even on the sharing of intelligence)—though that could well have taken place behind closed doors. Perhaps it implies that the grouping is not heading towards a military alliance—at least not overtly. Much of it could be to allay Chinese concerns. But Quad does have the scope to add a greater security architecture at a later juncture. As for now, the very coming together of democracies provides an alternative in the region, which could be the balance to China.

The Unfolding of AUKUS

While Quad is emerging as the defining alliance of the Indo-Pacific, another alliance—AUKUS, comprising Australia, UK and USA—is providing another dimension. This recently unveiled initiative will provide Australia with the technology to build and deploy eight nuclear submarines. The first of these will be rolled out by 2030 and the fleet operationalized by 2040. The submarines will use nuclear propulsion but will not be armed with nuclear weapons—since Australia is signatory to the NPT which bans the deployment of nuclear weapons. This is the first time the USA is sharing sensitive nuclear technology with a partner (less UK) and will give offensive teeth to the Australian Navy that will extend to the Chinese waters.

The pact has come after months of back door diplomacy, even though its sudden announcement came as a surprise. It was Australia’s pushback after years of Chinese bullying and pressure tactics—which included banning Australian imports because Canberra criticised China’s record on human rights. One paper even jokingly suggested that the first boat should be name Xi Jinping for his role in pushing Australia towards the path.

Besides China, another nation that has been peeved by the announcement is France. Australia had entered into a USD42 billion deal with France to build 12 diesel electric submarines for its navy. This was abruptly scuttled in favour of US nuclear submarines in a very Trumpesque move, leading to a diplomatic storm in which France recalled its ambassadors from Australia and the US.

The signing of a new Indo-Pacific accord by two Quad members, without even keeping the other two in the loop is a little jarring. But in a way, it is a welcome step. AUKUS is a definite security mechanism (which could lead to US bases in Australia and a more robust military presence in the Indo-Pacific) and can provide the military muscle which Quad seems to lack as yet. There had been talk of Quad developing into an ‘Asian NATO’ which would provide the security umbrella for the region. There was even talk of it evolving into Quad Plus to include Singapore, Malaysia, and even UK. How far will Quad go to become a security apparatus now remains to be seen. US and Australian commitment to it could be diluted with AUKUS. And while Quad and AUKUS could operate in tandem, it would be best for the members to clearly identify the aims and goals of each. Only then will they be able to work in cohesion for their long-term goals in the Indo-Pacific.

Minister Scott Morrison at the launch of AUKUS grouping

Quad already has a military component in place, with the annual Malabar exercises that incorporates all four members (Australia joined in 2020). UK and French ships have been operating with the Indian Navy in these waters which is indicative that Europe too is shifting focus towards the Indo-Pacific. Malabar could thus expand in scope and help complement the objectives of AUKUS.

Implications of Both

With the strengthening of Quad and the unveiling of AUKUS, the long-awaited US tilt to the Indo-Pacific seems to be finally fructifying. India has shrugged off its decades of strategic reticence and has adopted Quad whole-heartedly. For too long we had been overly sensitive to Chinese concerns.

India’s tilt towards the Indo-Pacific will help us overcome the encirclement that China seems to be weaving to our West. Pakistan, Iran and now Afghanistan are slowly coming under China’s sway. The loss of Afghanistan is a huge blow to our strategic aspirations in Central Asia and the growing alliance of China-Russia-Iran-Pakistan and perhaps Afghanistan, is a direct threat on our western flank. Extending our sphere of influence towards the Indo-Pacific will help overcome it to some extent. However, we must never forget that our prime interests and main strategic concerns lie to our immediate west. The US and the other Quad partners must help balance our role in the Indo-Pacific by maintaining our strategic interests in the West—something the US seems to have brushed under the carpet with its abrupt abandonment of Afghanistan.

And though India should pursue Quad actively, it should do so with caution. The US has not proved to be a very reliable ally in the past—especially when the chips are down. So, India’s traditional partner, Russia, should not be lost sight of. That long-standing relationship should be nurtured even though Russia is fast veering towards China. Bilateral ties with Japan, France and Australia should be followed. In fact, India could utilise France’s submarine capabilities and the dormant infrastructure following the scuttling of their submarine deal with Australia, to augment its own submarine fleet. And though ties with China will remain adversarial for some time to come, we can still work together on common issues and reach some kind of working relationship—provided the vexed border issue is resolved.

Quad has the potential to evolve into the defining partnership of this century—just as NATO was for the earlier one. But it could also dissolve like the proverbial seafoam, unless it is nurtured. India can play a huge role in that—including hosting the next summit in Delhi. But at the same time, we must keep our strategic interest in mind by developing bilateral and pluralistic ties with other nations and not place all our eggs in the US basket.

(The writer is author five books)