India-US relationship has been a rollercoaster ride until now

Smruti D

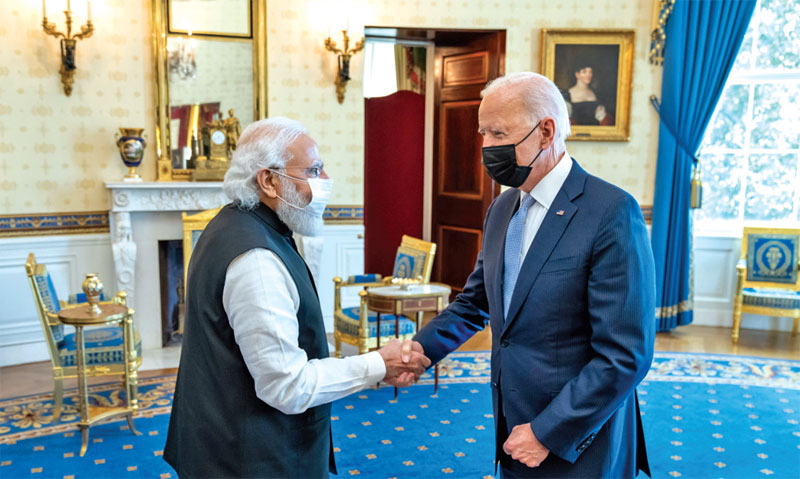

Nothing could have better encapsulated the ebb and tide of India-US relationship than the recent visit of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Despite the hype in India, even his greatest admirers conceded that the new US administration was remarkably cold towards the Indian Prime Minister in the sharp contrast to his last visit during Donald Trump’s tenure.

Either President Joe Biden was still smarting from Modi’s partisanship in announcing ‘abki baar Trump sarkar’, or he was conscious that post-Taliban sweep in Afghanistan, the geopolitics of the region has changed so rapidly that it really has nothing much to offer India at the moment beyond what has already been served.

Those with a sense of history would dismiss this as the nature of the relationship between two ‘natural allies’. While democracy is frequently invoked as a natural binder, India and the US have several other shared interests and concerns. Equally, the national interests of the two often conflict with one another. The biggest example of this has been India’s strategic ties with Russia.

Washington has frequently expressed displeasure with India for buying defence equipment from Russia, which remains one of India’s biggest suppliers of military hardware. A year ago, when India was poised to sign the USD 5.5 million agreement with Russia for the S-400 air defence missile systems, the US warned India that the deal could attract US’ Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA). A senior US official was reported to have said, “We urge all of our allies and partners to forgo transactions with Russia that risk triggering sanctions under the CAATSA. CAATSA does not have any blanket or country-specific waiver provision.” India went ahead with the S-400 deal.

“The problem we face with respect to India must be separated from the larger issue that’s about the CAATSA legislation,” says Ashley Tellis, Tata Chair for Strategic Affairs and Senior Fellow, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He was speaking at the recent event, ‘Implications of CAATSA on US-India Relations’ organised by the USISPF. “I am actually quite sympathetic to the CAATSA legislation because I see that as a justified response on the part of the US to what Russia has done… One can hold that the CAATSA legislation is justified but its application to India is not… The CAATSA legislation that is applied to India is fundamentally counterproductive,” he said.

According to Tellis, there are two clear reasons for why this waiver justification is tellable here. “First is that India is not a US ally and therefore, India’s freedom to trade with Russia should not be impacted by the US domestic legislation. We never had the expectation when we were working on the transformation of the US-India relationship that India would cut off ties with its own partners around the world. We had very difficult discussions that time, with respect to India’s relationship with Iran and we reached mutual accommodations because both sides were respectful of the autonomy in foreign policy-decision making that both sides treasure. It is completely consistent in my mind to hold Turkey to sanctions because its alliance membership subverts our collective obligation to mutual defence in a way that a waiver for India does not in any way implicate because we have no collective defence agreement. India’s acquisition of the S-400 does not undermine the US military policy in any way.”

The second, he said is that “The reason why India wants the S-400 is primarily to cope with threats posed by China and anything that India does to strengthen its defence in the face of an increasingly assertive China is something that the US should simply encourage. There are limits to which the US can go in terms of providing India an effective defence against China. But there should be no constraints on what India should be permitted to do in terms of beefing up its own defence against China.”

The nuance that Tellis refers to is what has been shaping the relationship between India and the US. Says director, Studies and Head of the Strategic Studies Programme, Observer Research Foundation, Harsh Pant, “The US and India are both facing a structural problem in the Indo-Pacific. The US is facing the challenge of China and India is facing a rising power in its neighbourhood, which is putting pressure on Indian policy priorities, from borders to its diplomatic outreach in South Asia and the Indian Ocean Region. Naturally, there is a convergence between Washington and New Delhi as they don’t want any one country to be the predominant player in the Indo-Pacific, especially China.”

Strategic Ties

In pursuance of closer ties with the US, India have signed all the crucial foundational agreements that the US had put on the table, despite misgivings in certain quarters in India. The US has held the General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA), Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA), Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement (COMCASA) and Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement (BECA) as the key to increased cooperation with India.

The last of these agreements that India signed in November 2020 was BECA. This agreement would enable India to get real-time access to American geospatial intelligence that will enhance the accuracy of automated systems and weapons like missiles and armed drones. India can then access topographical and aeronautical data, and advanced products that will aid in navigation and targeting. This will enhance cooperation between the two air forces.

However, defence experts believe that by signing the BECA India has handed over the digitised military capabilities of its three defence forces to the US. In one of his columns, FORCE editor Pravin Sawhney writes, “With the signing of Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement (BECA), India has potentially mortgaged digitized military capability of its three services—army, air force and navy—to the United States.” He adds that through the twin-routes of datasets (given under BECA) and the systems (given under COMCASA), Indian indigenous kill-chains (sensors to shooter networks working through command centre) would potentially be under US’ control through its humongous cyber capabilities.

The LEMOA which was signed in 2016, allows the militaries to replenish from each other’s bases, and access supplies, spare parts and services from each other’s land facilities, air bases, and ports, which can then be reimbursed. Given the strategic waters of the Indo-Pacific, the navies of the two countries would gain advantage using each other’s ports.

The COMCASA allows India to use the US’s encrypted communications equipment and systems so that military commanders, aircraft and ships of the two countries can communicate through secure networks. Together, these are aimed at securing interoperability in peace and in war. While the US had been urging India to sign these for years, the Indian armed forces as well as the government in the past had been sceptical about it, citing strategic autonomy as the reason for resistance. Another Indian worry was leakage of crucial data to other countries.

Diplomacy

The two countries are a part of several common multilateral organisations, including the United Nations, G-20, Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Regional Forum, International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and World Trade Organisation.

India is an ASEAN dialogue partner, and an observer in the Organisation of American States. India is also a member of the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA), in which the US is a dialogue partner. In 2019, the United States joined India’s Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure to expand cooperation on sustainable infrastructure in the Indo-Pacific region.

In September, when Prime Minister Modi was in the US, President Biden reiterated America’s support for India’s inclusion in the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) and as a permanent member in the UNSC. However, for all this convergence of interests, according to a paper published by the Stimson Centre, India’s alignment with the US stands at 20 per cent, as opposed to 80 per cent of both Japan and Australia.

Arms Sales

According to the data released by the Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA), a part of the US Department of Defense (DoD), India’s weapons procurement from the US jumped from a meagre USD 6.2 million to a whopping USD 3.4 billion in the final year of Donald Trump’s administration. This came at a time when several countries reported a drop in purchase of weapons from the US.

The 2020 edition of the Historical Sales Book records that India purchased weapons worth USD 754.4 million in 2017 and USD 282 million in 2018. Between 1950 and 2020, US sale of weapons to India under Foreign Military Sales (FMS) category was USD 12.8 billion. According to the Stockholm International Peace Institute (SIPRI), Russia’s share of the Indian market fell to 58 per cent from 76 per cent between 2013-2018. In this brief period, the US held the second place as arms supplier to India.

However, the new statistics released by SIPRI state that India’s overall defence imports, along with imports from the US have gone down. The US now holds the fourth place in the list of arms suppliers to India. The report stated, ‘In 2011-15, the US was the second largest arms supplier to India, but in 2016-20 India’s arms imports from the US were 46 per cent lower than in the previous five-year period, making the US the fourth largest supplier to India in 2016-20.’

The US lost a bit of its leverage as several procurement plans remained stuck. Meanwhile India bought equipment from countries such as Israel and France. In 2016, the US conferred the status of a ‘major defence partner’ upon India, which sought to ease the procurement of weapons systems, spares for platforms already in Indian inventory and the transfer of technology with the new status. This was announced at a US-India joint statement when US secretary of defence Ashton Carter visited India that year. The joint statement acknowledged that the US-India defence relationship as a possible ‘anchor of stability’, with the US saying it will ‘continue to work toward facilitating technology sharing with India to a level commensurate with that of its closest allies and partners’.

In 2018, the US elevated India to the list of most-important allies. This aimed at easing export restrictions for high-technology product sales to India by designating it as a Strategic Trade Authorization-1 (STA-1) country, a list consisting of 36 countries. While most countries on the list are members of NATO, India became the third Asian country after Japan and South Korea to be included. Earlier, the 2005 New Framework for the US-India Defense Relationship expressed the goal of increasing the defence trade between the two countries. In 2011, the US took steps to realign its export control regulations towards India that paved the way for defence cooperation between the two countries. The countries hold the Defence Technology and Trade Initiative (DTTI) Group meetings twice every year.

DTTI was formed in 2012 between India and the US, to enhance bilateral defence relations by undertaking advanced defence research, development and manufacturing. It sought to move away from the ‘buyer-seller’ rhetoric by creating ‘co-production and co-development of defence equipment.’ Only last year, in September 2020, the two countries held their tenth meeting, virtually. Four Joint Working Groups focused on land, naval, air, and aircraft carrier technologies were established under DTTI to promote mutually agreed projects within their domains. In September 2021, India signed a Project Agreement for Air-Launched Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (ALUAV) under the DTTI.

India has bought several defence equipment from the US under Foreign Military Sales. Only recently, in August 2021, the US approved the sale of Harpoon Joint Common Test Set (JCTS) and related equipment to India for an estimated cost of USD 82 million. The Harpoon is an anti-ship missile. Earlier in May, the US cleared the sale of six P-8I patrol aircraft to India worth USD 2.42 billion. Along with the Harpoon, the US also approved the sale of MK54 lightweight hybrid torpedoes to India. These are anti-submarine warfare torpedoes developed by Raytheon. India has also leased two MQ-9B SeaGuardian UAVs in November 2020.

The other equipment that India has bought from the US include fixed wing aircraft like C-130J, C-17 and P-8I; helicopters like MH-60R, Apache and Chinook; and M777 ultralight howitzer.

Military Exercises

In 2019, India-US held the nine-day humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) exercise code-named ‘Tiger Triumph’. The armies of the two countries also conduct Exercise Yudh Abhyas. In February 2021, the 16th edition of the exercise was conducted in Rajasthan. The aim of the exercise was to focus on counter-terrorism operations under the mandate of the United Nations.

Exercise Vajra Prahar is undertaken by the Special Forces of the two countries. In March 2021, the 11th edition was held in Himachal Pradesh. In December 2018, air forces of the United States and India participated in a 12-day joint exercise ‘Cope India 2019’ at two air force stations in West Bengal. The Cope India exercise was held after a gap of eight years, with the last one having taken place in 2010. India is also a part of the multilateral air exercise ‘Red Flag’.

The deepest military engagement is between the two navies. It is helmed by Exercise Malabar, which started as a bilateral exercise but eventually became multilateral with Japan and Australia joining in. Today, this has transformed into the Quad exercise, with the biggest one taking place in August 2021. Royal Australian Navy (RAN), Indian Navy (IN), Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF), and the US Navy participated in it. In one-of-a-kind exercise held between the IAF, Indian Navy and the US Navy in June 2021 in Thiruvanathapuram, the forces were engaged in joint multi-domain operations with the Carrier Strike Group comprising Nimitz class aircraft carrier Ronald Reagan, Arleigh Burke class guided missile destroyer, USS Halsey and Ticonderoga class guided missile cruiser USS Shiloh. The IAF fighters Jaguar and Su-30 MKI along with airborne early warning and control systems (AEW&C) and air-to-air refueller aircraft were part of the exercise.

Also Read:

Caught Between Acronyms

Could AUKUS undermine QUAD in the long run?