Broader strategic planning is crucial to carry out contingency response successfully

RAdm. Sudhir Pillai (retd)

RAdm. Sudhir Pillai (retd)

I know a lot less about economics than I do know about military and foreign policy issues. I still need to be educated

— John McCain

This quote is good advice not just for India’s military leadership but also for our foreign policy and economics elite. From a military professional point of view, investments below a level can impact military readiness and can hamper the ‘bang for the buck’. This article seeks to analyse what current day realities about India's economy means for Indian military effectiveness.

The Raison d'être

A newspaper headline on January 9, read ‘Navy on standby for emergency evacuation of desis’. The article also stated as to how the mission could see India deploying the C-17 Globemaster for any evacuation that may be required. The headline followed the Iranian missile strikes on the US-led forces in Iraq and the fear that it could escalate into a broader conflict in the Middle East.

Militaries are maintained and exist for contingency responses such as these to protect vital national interests. The deployment of military, rather than civilian capabilities that the government owns, follows the need to cater to the potential of armed opposition in humanitarian missions. Such contingencies requiring the use of armed force are not rare, and, has often been necessary. Responses may require breaching that escalation threshold that one would never like to cross. It's this thin line separating the varying calibrated responses required that could reveal how military capability can be the yardstick that permits such interventions or could also highlight limitations that may prevent an effective intervention or evacuation.

As I wrote this article, another headline caught my eye which read ‘Fund-hit Navy set to scrap Rs 20K crore tender’. According to the article, ‘the Navy is the “first among the armed forces” to finalise a “rationalisation plan” for its capital acquisition projects, which ranges from “withdrawing some tenders” to “reducing numbers” in other mega programmes. The Defence Acquisitions Council to be chaired by defence minister Rajnath Singh on January 17 will discuss all this’.

It appears that India’s expansive military plans and the Indian Navy’s Maritime Capabilities Perspective Plan 2012-2027, the XII Plan Document, the XII Infrastructure Plan Document, the Indian Navy Indigenisation Plan 2015-2030 would all stand affected. To analysts, it would appear that the Indian Navy has little choice but roll back plans, given the grim economic realities that India confronts.

The Navy Chief Admiral Karambir Singh’s declaration that his force is ‘committed to modernisation using available resources optimally’ is reminiscent of a policy another Navy Chief Admiral Ramdas had to adopt that read ‘much more with much less’. Admiral Ramdas served as naval chief from 1990–1993, during an infamous period, when India had to pledge her gold reserves for a sizeable conditional bailout from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank.

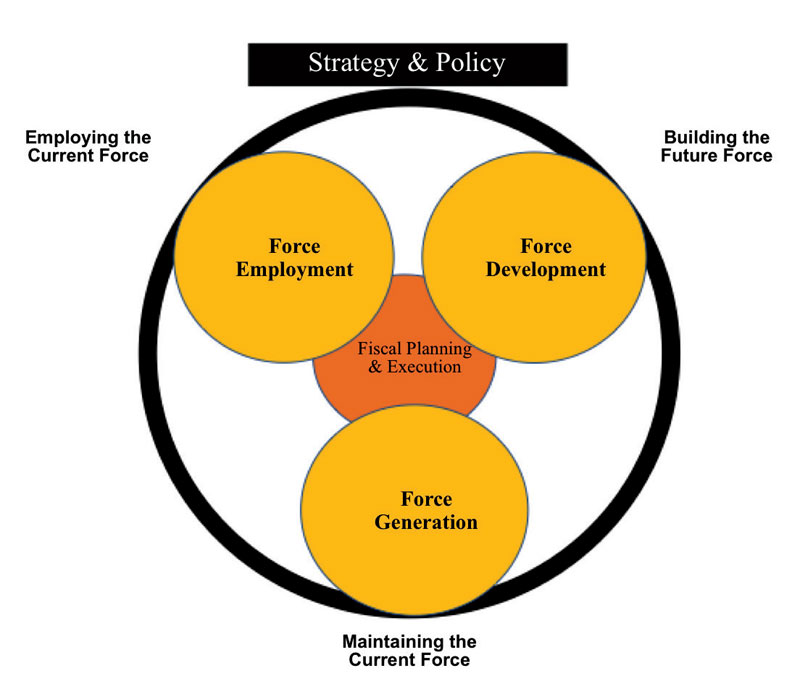

With this as a background, we need to raise serious questions that most professional militaries ask of their political masters but are often not taken too seriously nor answered. This till the governments have to look at the military for options. This question has at its core the eternal ‘resources versus capabilities’ or the ‘guns vs butter’ debate which is the central theme of this article.

Operation Khukri

Permit me to highlight through a not too well-known episode in India's recent military history, when resource constraints forced India to look at external sources for support, and a bailout. Such a moment of truth came about when India, now well on a path to economic recovery, had committed its military to an apparent benign mission of disarmament of rebel forces, in far-flung Sierra Leone in West Africa in April 2000.

As part of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL), India deployed substantial forces for the mission which besides regular and mechanised infantry, would soon include 2 PARA (SF) and induction of Mi-35 attack helicopters. With the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) rebels disarming 500 Kenyan ‘peacekeepers’ the situation was worsening in May 2000. A thin line was getting breached, and the peacekeeping mission was rapidly evolving into more than that, requiring the use of arms and peace enforcement. The Quick Reaction Force of an Indian Battalion had to be launched into a 180 km armed advance, in armoured vehicles, pushing back several ambushes in a mission that sought to rescue the Kenyans.

Meanwhile, the situation at Kailahun where two companies of 5/8 Gurkhas of the Indian Army was based, was besieged by hundreds of RUF rebels. The Battalion’s Second in Command (2IC) who was despatched with a patrol to negotiate the release of the hostages at Kailahun, would find themselves surrounded by about 200 rebels, detained and taken as hostage. The hostage crisis at Kailahun was resolved ten days later through intense pressure put on the RUF commanders. The enlarged mission would need induction of substantial additional forces, and these included some from a brigade de-inducting from Siachen!

You must be logged in to view this content.