A limited war will not be to China’s advantage (September 2010)

Pravin Sawhney & Ghazala Wahab

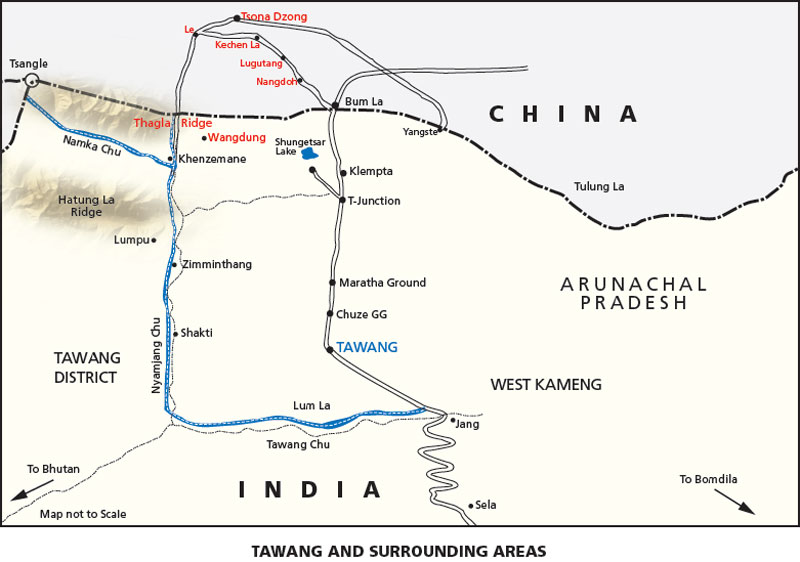

Tawang : Given Chinese diplomatic and military assertiveness against India especially after the 2008 Beijing Olympics, FORCE has been pondering over the question which was recently set up for polls by China’s People’s Daily newspaper, known mouthpiece of the Chinese Communist Party: ‘How likely is China’s launch of a limited war against India?’ The response was more ayes than nays. We asked a number of senior military officers as to what would be China’s military aims in a limited war. Considering that China, under the garb of differing perceptions of the border on both sides, has been nibbling at Indian territory since over a decade, and has created many more disputed pockets, prominent being the Pangong Tso lake in western sector, along the 4,056km Line of Actual Control since 1995, a limited war over tactical gains makes little sense. In 1995, during the eighth round of the Joint Working Group, both sides had agreed to only eight ‘pockets of dispute’. These are Trig Heights and Demchok in the Western sector, Barahoti in the Middle sector, and Namka Chu, Sumdorong Chu, Chantze, Asaphila and Longju in the Eastern sector.

China, after the 1986 Sumdorong Chu crisis, has adopted a tough border negotiating position, withdrawn the ‘Deng package’ meant for border resolution, and has claimed the entire state of Arunachal Pradesh (AP) as being the three districts of lower Tibet, namely, Monyul, Loyul, and Lower Zayul. Considering that no self-respecting nation can barter so much land for peace (90,000sqkm of AP), the seeds of the future conflict between India and China lie in the Eastern sector. Military officers say that claiming the state of AP is mereposturing by China as it would involve a protracted high intensity war, which will lead to Nuclear escalation. What about a limited war over Tawang? According to them, that could be a possibility. This set the stage for the FORCE team’s visit to Tawang, where having spent a week, we concluded that the Indian Army is taking the defence of Tawang seriously. While no one said that 2012 is the deadline when the Indian Army would be more than prepared to meet the challenge of a limited war over Tawang, all indicators suggested that the preparedness afoot would close to this timeline.

Within limitations, the army is doing a commendable job for the defence of Tawang. The morale of troops in the sector is high. The high altitude rations are good, full authorised leave is available to all ranks (officers get curtailed leave, while the remainder gets en-cashed), extreme winter clothing has improved (though snow boots are in short supply), and high altitude allowances for officers and all ranks are satisfactory. “The high altitude rations include branded juices, dry fruits, chocolates, and all these are very helpful as appetite for normal food diminishes at such heights,” said an officer. There is special mention of sleeping bags whose quality is good. “A warm sleeping bag and dry ration are things that all ranks keep with them when moving out of their units as given the road and weather conditions, a timely return is always doubtful,” explained a subedar.

During the time FORCE team spent in the area, it was evident that the Chinese soldiers no longer appeared seven feet tall. Tactical level commanders do not speak merely about the defence of Tawang; instead they hint at offensive operational plans to avenge the tactical losses of the 1962 war and the 1986 crisis should China initiate a limited war in the region. The Line of Actual Control is referred to as the ‘border’ by everyone suggesting that unlike the military held line which can be altered by force, the ‘border’ is unambiguous and will be guarded at all costs. When asked about the growing assertiveness of Border Guards (Chinese quasi- paramilitary forces facing Indian troops in TAR), officers concede that the earlier bonhomie is missing at times. At places where the two forces are within shouting distance or when the two opposing patrols would meet, the Chinese would be pleased to ask Indian troops for local cigarettes and accept a hot cup of tea. Such occurrences have decreased; the Chinese patrols evidently have orders to be more firm and aloof with their Indian counterparts. “There is a palpable stiffness on faces of Chinese soldiers which was not there earlier. This could be an indicator of things to come,” said a major who has been in the area since two years.

All Indian infantry deployments in the sector are ahead of Tawang. The entire 190 mountain ‘Korea Brigade’ of the 5 mountain ‘Ball of Fire’ holding division is permanently in high altitude posts ranging from 10,000 feet to over 15,000 feet ahead of Tawang, while the other three infantry brigades of the division have permanent defences on these heights which are regularly maintained during ‘operational alert’ period; the time when formations cross the Se La ridge line and occupy their operational defences for maintenance and operational familiarisation. Considering that the army has adopted the extreme forward posture and extensive regular patrolling is done, road communications are unsatisfactory. The holding division occupies over 200 posts ahead of Tawang, many of which are devoid of tracks where vehicles can reach. Troops march anything from a few hours to two days from Tawang road (track) head to reach their posts lugging essentials. The answer found in employing locals as porters or helidrop of loads are a temporary reprieve and would be unsustainable during war.

To assuage difficulties faced by troops, the army in 2009 started a pilot High Altitude Habitat project in the division’s area of responsibility (AOR). This comprises Fabricated Reinforced Plastic (FRP) huts available in white and green colours to provide natural camouflage. These huts are quantum improvements over existing shelters used by troops during acclimatisation periods (acclimatisation is extensive; six days for stage one at 10,000 feet, and four days each for the next two stages at 12,000 feet and 15,000 feet) which are inadequate for extreme winter conditions. Moreover, as permanent accommodation at each acclimatisation area is limited, troops when inducted in large numbers will be forced to stay in tents before occupying forward defences. Such a situation will impact adversely on soldier’s fighting capability. The new habitats will be available in different sizes to accommodate various troops’ configurations like section to platoon strengths and will have integral heating system with available running hot water. Officers say that this project is on high priority, and once approved, large numbers of FRP huts are expected to be acquired starting 2012.

Troops here are conscious of the three tactical advantages of the opposing Chinese border guards. One, the Chinese side has proper gravel roads right till the LAC. The road communications on the two sides can be seen at the Bum La meeting place. It is stark and disturbing. The Chinese have deliberately avoided to make ‘black-top’ road as the gravel allows better water drainage during monsoons, and it puts pressure on the Indian side to not make ‘black top’ roads on its side. In any case, officers say, the Chinese have the capability to easily construct up to 45km of ‘black top’ road in 90days. Their road construction workforce is inclusive and well-disciplined. The other advantage enjoyed by Chinese troops is psychological. They seem to be under no pressure to maintain round the clock forward vigil. Chinese border guard force levels in forward positions are inversely proportional to Indian troops’ deployments. The Chinese are content with using a plethora of tactically networked surveillance means which are monitored regularly. They rely on technology much more than the Indian side. The Chinese brigade facing Tawang is 2 border guard regiment (brigade sized) based about 40km at Tsona Dzong. Between their defences at specific and sensitive forward places and their regiment headquarters, the Chinese have flat barren ground, suggesting their reliance in the Rapid Reaction Divisions (RRD). And lastly, Lhasa being an important communication hub is very well-provided and connected with oil pipelines and road network.

Weather and terrain favours the Chinese. Unlike Indian troops who have to go through the rigour of three-stage acclimatisation each time they come to occupy forward defences, the Chinese on the Tibetan plateau at heights of 16,000 feet and above are always acclimatised. The terrain on the Chinese side has gradual gradient as compared to the Indian side which suffers from what the army calls ‘friction of terrain.’ This leads to frequent landslides and can cause havoc especially during rains. Thus, a monsoon campaign in this area would benefit the Chinese troops. According to senior tactical commanders, the Border Roads Organisation has set 2012 deadline for two-lane road till Tawang, and beyond for good communications.

In a limited way, and more by default, the weather and terrain also work as an equaliser. The extreme cold, broken terrain and fast changing weather on the LAC plays havoc with electronic equipment. Tactical net radio in the HF/VHF/UHF ranges work erratically, seizure of equipment and weapons due to cold arrest is never ruled out, as siting of equipment in terrain where visibility is poor and unpredictable is a problem. The Indian artillery, if available in requisite numbers, will have an edge over the PLA artillery. Deployed on the reserve slopes it will be difficult to target by enemy’s counter-fire. The infantry firepower with direct fire application of both sides is comparable. The rough mountainous terrain will force both sides to use rocket propelled grenades and automatic grenade launchers in direct fire application during advance, as the artillery mass would lag behind or get diluted because of inadequate deployment space.

In a limited way, and more by default, the weather and terrain also work as an equaliser. The extreme cold, broken terrain and fast changing weather on the LAC plays havoc with electronic equipment. Tactical net radio in the HF/VHF/UHF ranges work erratically, seizure of equipment and weapons due to cold arrest is never ruled out, as siting of equipment in terrain where visibility is poor and unpredictable is a problem. The Indian artillery, if available in requisite numbers, will have an edge over the PLA artillery. Deployed on the reserve slopes it will be difficult to target by enemy’s counter-fire. The infantry firepower with direct fire application of both sides is comparable. The rough mountainous terrain will force both sides to use rocket propelled grenades and automatic grenade launchers in direct fire application during advance, as the artillery mass would lag behind or get diluted because of inadequate deployment space.

FORCE looked at the possibility of China initiating a limited war. This implies Chinese capability to bring three to four RRDs on the Tawang sector in short time. Army officers here say that at least 10 to 15 days warning will be available to troops on the ground of Chinese starting a limited war. This will be enough time for forward defences to be manned fully adopting an offensive posture. The Indian Army will have the capability to bring three to four divisions matching the Chinese against Tawang. An edge over the Chinese can be achieved by 2012 if the government fully supports the army’s war preparedness. This would entail addressing three issues on a war-footing. The first concerns the forces-in-being.

With the raising of two new divisions, 71 and 56 mountain divisions, there have been changes in the order of battle of the two corps in the sector. The 4 corps will remain the holding corps, while the 3 corps will have an offensive role. Once the recently raised mountain divisions (the raising was declared completed on March 31) acquire their due strength and equipment (there are signs on the ground of new forward ammunition dumps being built tugged inside the natural mountain camouflage), these forces will have the capability to achieve a tactical offensive. The second issue requiring government attention is landbased firepower (field artillery). Given the weather and terrain conditions in the sector, only long range artillery will come in handy for the depth battle and interdiction of enemy supply lines to forward forces. The need is to acquire the ultra-light howitzers soonest which can be heli-dropped, as well as move the Smerch and Pinaka multi-barrel rocket launchers into the sector. This brings us to the third issue: need for better road communications. Once this happens, the Indian artillery will have an edge over the Chinese land-based firepower, and this along with the high morale of troops will be the limited war-winning factors.

It can thus be argued convincingly that a limited war will necessarily result in a stalemate over Tawang; this situation would be damaging to China’s stature. Given India’s military preparedness, China will not take the risk of a limited war. The China of today is different from what it was during the 1962 war and the 1986 Sumdorong Chu crisis, when it sought tactical gains. Once China brings in its air force (PLAAF) in a big way into the war and introduces the plethora of ballistic missiles, it will be a high intensity war unrestricted in time and space.

A High Intensity War?

Before appreciating the need for an unlimited war, it would be pertinent to understand the backgrounder on Tawang, the trigger place for the 1962 war as well as the 1986 Sumdorong Chu crisis that saw the two armies in eyeball-to-eyeball confrontation for a season. Questions that need to be answered are: Why is it important for India to defend Tawang? What are the lessons of the 1962 war and the 1986 crisis? Given the known military doctrines, strategic and operational imperatives of the two sides, is the India military prepared for a unlimited high intensity war? If not what needs to be done?

It is a truism that China’s occupation of Tibet will remain incomplete without the Tawang Tract, which corresponds to the Tawang and West Kameng districts of AP. According to the Chinese, the Tawang Tract is situated between the Tibetan plateau and the Assam plains, and a traditional route runs through it. Geographically, Chinese divide the Tawang Tract into two regions with the Se La range (13,700 feet) serving as the dividing line. To the north of the Se La is the great Tawang monastery, the second largest in Asia, and the winter residence of the Dzongpons (high officials) of the Tsona district in Tibet. The Dzongpons as representatives of the Tibetan authorities directly administered the entire Tawang Tract, with Senge (south of Se La) being their private estate. Moreover, the sixth Dalai Lama was born in Tawang in the 17th century. Beijing thus knows that India’s formal acknowledgement of Tibet being a part of China is half the story. The other half must await the passing away of the 14th Dalai Lama who lives in exile in India since 1959, and the subsequent return of the Tawang Tract territories to China.

The Tawang Tract is the singularly important reason why China will not resolve the border dispute with India in the foreseeable future. This was also the bilateral sticking point of the ‘Deng package’ which was last offered between 1982 and 1985 to Prime Ministers Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi. In the ‘Deng package’, less the Tawang Tract, China was agreeable to accept Indian sovereignty in the eastern sector (AP) if New Delhi agreed to abandon its claim over Aksai Chin (already under Chinese occupation). Deng was even willing to consider (what is today) the Tawang district of AP instead of the Tawang Tract. But 1985 was a different time. The Cold

War was on and China as a weak nation balancing strained relations with the Soviet Union and the United States did not want another front against India. Moreover, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had demonstrated political resolve and acumen for national security in equal measures, something that Chinese respect. From New Delhi’s perspective, Tawang could not be lost as long as Tibetans had political asylum in India, and Tawang provided the shortest route between India and Tibet. Thus in 1980, when the then army chief, General K.V. Krishna Rao presented Prime Minister Indira Gandhi with a strategic military plan called Operation Falcon, it was accepted without delay, and this did not go unnoticed by China.

Operation Falcon envisaged converting the patchy forward presence against China into a heavy forward deployment on the arc from Turtok and Shyok (Ladakh), all the way to the India-Tibet- Myanmar tri-junction. Arunachal Pradesh, North Sikkim and the Trans- Ladakh range were to get special attention. The heavy deployment would be undertaken over a 15-year period in which forward build-up would keep pace with infrastructure development along with viable lines of communications. The only political term of reference given by Mrs Gandhi for Operation Falcon was to ensure that in a war with China, Tawang must not fall again as it did in the 1962 war. Regarding the operational stance, military commanders felt that army divisions should be sited after having learnt the lessons of the 1962 war at great costs. Instead of going through the sterile debate of holding the Se La and Bomdi La line in strength, the whole mass was to be pushed forward with Tawang as the centre for Kameng district and Walong for the Lohit district. The army chief, General K. Sundarji was to adopt this stance during the 1986 Sumdorong Chu crisis.

Interestingly, this remains the operational stance even today with Tawang as the 4 corps’ vital defended area. Unfortunately, between 1988, on the eve of Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s famous visit to China, and 2003, when Prime Minster A.B. Vajpayee visited China and sought border resolution through special representatives, Operation Falcon was abandoned to appease China. Between 2003 and 2008, New Delhi dithered on the quantum of support to Oper- ation Falcon without displeasing China. Ironically, as Delhi remained comatose about the Chinese front, Beijing utilised these years to build-up excellent border management and military infrastructure along the 4,056km disputed Line of Actual Control. New Delhi finally woke up to the Chinese military threat in the wake of the 26/11 attacks by Pakistansupported terrorists in Mumbai in 2008. The question debated was that given China’s track record, what mischief will it make in case of a war between India and Pakistan? Indian military leadership finally convinced the political masters that Chinese support to Pakistan would no longer remain covert. Thus, in early 2009, New Delhi cleared the need for the military to prepare capabilities for a two-front war, with Pakistan and China. For the first time in independent India, defence minister A.K. Antony issued a written directive to the military on the expanded battlefields. What the latter implied was that full political support would be given to the military to build requisite capabilities.

What are the lessons of the 1962 war and the 1986 crisis? The Thag La ridge in Tawang district was the trigger place for both events. In 1962, China claimed the Thag La ridge line as theirs while India, going by the watershed principle, called it its own territory. Thag La was important for Chinese because on its northern slopes it had a large Tibetan village called Le, which was the obvious site for the Chinese forward base for any operations against India in this sector. While the 1962 war campaign has been studied threadbare, a few glaring benchmarks need to be remembered to appreciate the present ground realities. A solitary overstretched 7 brigade was responsible for the defence of Tawang and to ensure sanctity of the nearly 150km McMahon Line in Kameng sector. Indian intelligence assessed that Chinese could bring a regiment (equivalent of Indian brigade) worth of troops in the Kameng sector, whereas they actually brought more than two divisions. Considering that all Indian Army posts beyond Tawang were maintained by air, it made them dependent on weather and thus untenable during war. In short, besides complete command breakdown, the 1962 war highlighted the need for better operational and tactical intelligence, adequate forces-in-being, good road communications, and the importance of operational logistics. Once Chinese declared the unilateral ceasefire, they held the Thag La ridge, which started the war, with them. It needs to be remembered that Chinese had started preparations for war well before they joined it. The commander of 7 brigade, Brigadier J.P Dalvi who was in Chinese captivity for seven months wrote that they had prepared accommodation for 3,000 prisoners of war.

The 1986 Sumdorong Chu crisis was the consequence of India’s military activism under the Rajiv Gandhi-General K. Sundarji team. The Indian Intelligence Bureau without knowledge of the Indian Army established an observation post in 1984 at a place called Wangdung in Sumdorong Chu of Tawang district. They used to occupy the post in summers and vacate it during the winter months. In June 1986, when the IB men came to occupy the post, they found it held by nearly 200 Chinese soldiers. This led to a toughening of positions by India and China each accusing the other of intrusion. Determined not to cow down and hoping to avenge the 1962 military debacle, the army chief, General Sundarji launched Operation Falcon as distinct from the one commenced by General Krishna Rao in 1980. General Rao’s military built-up was a 15-year stepby-step programme, which had already suffered time losses on account of Border Road Organisation’s tardiness. Into its sixth year in 1986, General Sundarji gave it a military push to match Chinese build-up.

At the peak of Operation Falcon deployments in 1987, three mountain divisions of 4 corps headquarters were pushed towards the McMahon Line in AP. Two divisions were deployed in Kameng district to defend Tawang, and a better part of the third division was in Lohit district to defend Walong. Tawang was designated as the corps vital area, which had to be defended at all costs. Extremely strong artillery lements were placed in support of the troops. General Sundarji ordered airlifting of artillery ammunition estimated in crores of rupees to be stocked in forward areas. (After the crisis was over, this ammunition deteriorated in forward areas as it was not found cost-effective to be airlifted back). Interestingly, the first operational deployment of the Bofors FH-77B field howitzer purchased in 1986 was in Kameng district. The units deployed near Tawang commanded the complete area to which Chinese reinforcements would be sent in the event of a crisis.

Because of inclement weather in AP, air maintenance, whether by rotary or fixed wing aircraft, is never an advisable proposition. Reminiscent of the pre-1962 forward policy when troops were moved without logistics and communications tie-ups, the then army chief rashly moved 77 brigade close to Sumdorong Chu, which was maintained by air. The 77 brigade deployed three km short of the Thag La ridge held by Chinese troops. Without secure communications and logistics, two brigades of 5 mountain division dug in to ensure that the Namjang Chu approach to Tawang was denied.

By the spring of 1987, the PLA 63th field army from Chengdu military region was facing two Indian mountain divisions deployed in a holding role to secure Tawang. Headquarters 4 corps deployed a total of three divisions on the line with formations of headquarters 3 corps acting as reserves. To cater for an escalation of hostilities, vital areas and vital points which formed the framework of a border conflict with China received heavy to very heavy deployments catering to the entire border length, especially in North Sikkim.

At this stage, the army’s nightmare began. First, General Sundarji wanted 77 brigade to evict Chinese soldiers from the Indian IB post. The then Eastern army commander, Lt Gen. V.N. Sharma (later COAS) wanted to know how to respond to PLA’s tactical nuclear weapons supposedly in Tibet. In this context the defence minister of state, Arun Singh and General Sundarji told a press conference in New Delhi at the height of the crisis in spring 1987: “Indian forces will not fight with their hands tied.” This was not enough assurance for the army commander who sought a more credible answer.

Second, the 1986 crisis compounded operational problems. The army was heavily engaged in Siachen against Pakistan, and starting January 1987 had crashed into a fully mobilised deployment under Operation Trident in the west, which in turn was trigged by Operation Brass Tacks, and Pakistan’s consequent reaction of moving its army reserves north of the Ravi-Sutlej corridor against India’s Punjab. Little realised by the people of India, this was a full blown crisis for the nation: the nightmare of the two-front war against China and Pakistan was fast becoming a reality under General Sundarji. It was a panic situation and the army chief was certainly gambling; he pulled 6 mountain division from the Chinese front and moved it to the west against Pakistan. The government and the army command had placed the nation in an unenviable position. Somehow sense prevailed in New Delhi, Beijing and Islamabad and the situation was finally diffused. However, Wangdung in Sumdorong Chu remains with China. Thus, Thag La ridge and Wangdung posts that started the 1962 war and the 1986 crisis are firmly in Chinese control?

What next?

Given China’s advantages over India in border management and infrastructure development, and its risen global status where it views the United States as its sole competitor in Asia, a crisis or war over territories like Thag La and Wangdung, which can be explained by New Delhi ( face saving measures) as differing Line of Actual Control (LAC) perceptions, is unlikely. To assess the high intensity war matrix, a quick look at the bilateral strategic and operational levels is necessary.

China’s approach towards India is a mix of four elements: diffuse the core border issue; permit no political or diplomatic concessions; ensure through the strategic partnership with Pakistan that India remains a sub-regional power; and while rapidly building military power, employ psychological war to the hilt to ‘defeat the enemy without a battle.’ China scores heavily over India in decision making (the PLA is part of the Communist government) and strategic sustenance (product support) required for a long campaign beyond a limited war. Latter is possible as China will not brook international interference (including from the US) in case of hostilities with India. China has adopted the ‘limited nuclear deterrence’ doctrine suggesting a nuclear war-fighting doctrine. Considering that China has tactical nuclear weapons it may be tempted to use it against a determined enemy like India which has deployed defences in depth and will disallow an early tactical breakthrough to Chinese forces across a wide non-linear battlefield. A stalemate in a limited war will be interpreted as India’s win, something China, given its growing status is conscious about, and will avoid at all costs.

In operational terms, Chinese forces have numerous advantages over Indian forces. The PLA has a large number of short and medium range conventional ballistic missiles with good terminal accuracy which have bee integrated into theatre united campaign programmes. These missiles will be employed in conjunction with the air force (PLAAF) to allow the latter to retain sorties for achieving air superiority. Next, the PLA is preparing itself for a five-dimensional warfare; warfare in outer and electromagnetic spectrum in addition to land, air and sea. The PLA thus has acquired good cyberspace capabilities which can create havoc with Indian command, control and communication systems. During its recent Stride 2009 exercises, the PLA demonstrated improved triservice synergy, ability to operate in

unknown territory, good operational readiness of all formations at par with Rapid Reaction Divisions (RRD, an independent light mechanised division with high mobility structured for offensive operations), and substantive airlift capabilities (15th airborne corps based in Henan) needed for strategic missions to include occupying strategic points in the enemy’s rear, destroying the enemy’s key communication hubs, and preventing his supporting forces from reaching the front.

Next, the PLA has paid special attention to operational logistics and many innovative solutions have been found for operational sustenance required for high tempo battles in the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR). For example, considering that local resources for food, petroleum, oils and lubricants are sparse in TAR, and the main logistics feeder centres are far away in Chengdu and Lanzhou, the PLA has found an interesting solution. They have emplaced five to six logistics brigades in TAR. These formations will hold fast-expending commodities including fuel and ammunition stocked and dumped over time. Each logistics brigade is expected to support an infantry-heavy Group Army (GA), such that the tempo, defined as military activity relative to the enemy, is maintained. This brilliant plan will also help in overcoming the organisational weakness of PLA’s infantry divisions whose manpower is combat heavy with limited logistics component.

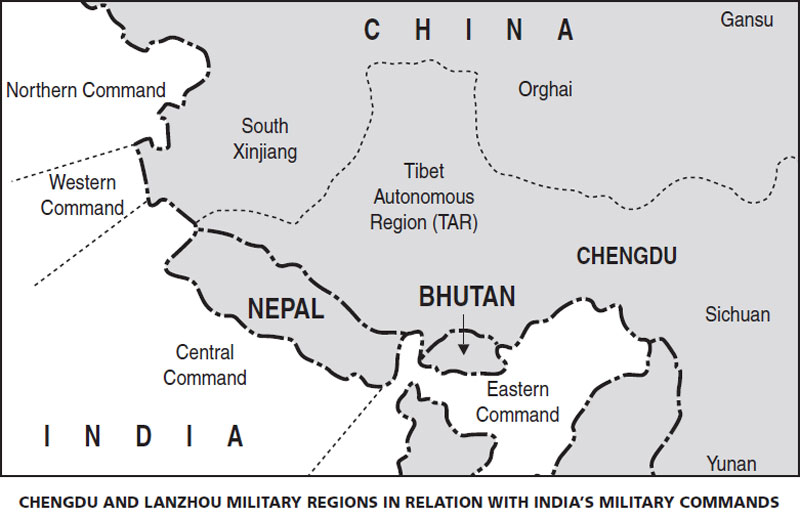

Unlike in the case of Indian forces which have separate air force and army command boundaries (within the army, four army command will be engaged simultaneously against TAR), the TAR is a single integrated command with integral air force (PLAAF) and conventional ballistic missiles. Benefits of a single integrated command need no elaboration. The Tibet military district facing India is the responsibility of both the Chengdu and Lanzhou Military Area Commands (MACs). This could mean one of the two things. Because two MACs are involved, the overall coordination for TAR facing India could be the responsibility of Beijing. Or, TAR could have a commanderin- chief headquartered at Lhasa, who would have under his command troops and aircraft from both MACs and the authority to draw operational level logistics sustenance from both. The second option is more probable. Each MAC has about three GAs, each equivalent to the Indian army’s corps, the minimum level where joint services operations are undertaken for independent frontal strike, deep penetration and rapid encirclement from all directions. Moreover, one GA in each MAC has an aviation regiment (equivalent of Indian brigade), which has heralded the shifting of operating principle of the GA from horizontal combination to vertical combination. India does not have anything remotely resembling an airborne corps.

It has been argued by Indian sources that the PLA has the capability to build up and sustain 20 divisions in TAR in a season for a wide frontal theatre campaign with deep battle considerations; simultaneous engagement of a given attack front in its entire depth and lateral spread. Regarding the air aspects, the PLAAF may presently be unable to sustain more than two air divisions (six regiments) in TAR. Even as most of the PLAAF airstrips have been lengthened, inclement take-off conditions would restrict weapons load. The PLAAF will also have to cater for an offensive counter- air capability of the Indian Air Force considering the latter has acquired appropriate weapons. From the Indian viewpoint, the IAF planners will have two worries. The PLAAF’s medium range aviation operating out of Yunnan province and interdicting the Brahmaputra valley, or an interdiction of the Indus valley by aviation out of Xinjiang; and long-range raid Special Forces dropped directly in the Brahmaputra valley. To pre-empt such situations, the Indian Army and the Air Force will need to allot high priority to an integrated air defence, as has been done in the west against Pakistan.

By 2020, the Indian Army will have the capability to bring five corps (3, 4, 14, 33, and the yet to be raised mountain strike corps) against China while keeping the Pakistan front in firm check. After pulling out up to four divisions from the west to east, the army could bring a total of 14 divisions to bear on the Chinese front. Once road communications improve, New Delhi could consider moving the Prithvi and Agni-I armed with conventional warheads against China. It is a myth to say that these are meant for Pakistan. No weapon system is country specific but can be used with adequate thought and planning against any adversary. Agni-I can hit Lhasa. Thus, while the army will check the PLA advance, the defining edge will need to be provided by the IAF, which by 2020, should have the capability to meet the two-front war challenge. The IAF and the army will need to work in close synergy to follow the eight to 10 offensive scenarios which have been successfully war-gamed with requisite capabilities. Chinese naval capabilities and nuclear weapons will remain the jokers in the pack as India will find it difficult to counter them. Chinese naval capabilities are growing at a fast pace, and without tactical nuclear weapons, India will remain at a disadvantageous position. The good news for India is that Pakistan will find it difficult to open a simultaneous war front against India to assist China’s unlimited war on India as long as the US forces stay in Afghanistan and Pakistan. All indicators suggest that this will be a long haul. Probably, the most important issue will be India’s political will which does not have an encouraging record to show.

What New Delhi should remember about China is that while it is not an expansionist power, it is a non-status-quo power, and will not give up territories which it considers are its own. India has little option but prepare for a two-front war in either form; an unlimited high intensity war with China while keeping Pakistan in check. Or a limited (in time) high intensity war with Pakistan while keeping a strategic defensive posture against an assertive China. While both scenarios could be a decade away, a limited war with China is certainly not in Beijing’s favour.

Also Read:

Ghost of ’62

Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high

Also Read:

Reaching Tawang

Visitors must be baptised by rain, landslides and blinding fog

Also Read:

The Spy Ring

India following China’s art of cyber warfare to give shape to an IT infrastructure setup

Also Read:

Debates and Delusions

Military build-up in Tibet provides China with multiple strategic advantages

Also Read:

War for Water

Water may turn into a defining bilateral issue

Also Read:

My First Responsibility is to Ensure that the Men Under my Command are Physically Fit and Battle-worthy

General Officer Commanding, 5 Mountain Division, Major General Anil K. Ahuja, VSM

Also Read:

Border Lines

BRO is the best and cheapest organisation for road-building in difficult terrains

Also Read:

Aerial View

Role of air power in India-China relationship

Also Read:

Embellished Truths

The Myth of India-China Economic Interdependence