The Myth of India-China Economic Interdependence (September 2010)

Zorawar Daulet Singh

Zorawar Daulet Singh

The spectacular trade trajectory between India and China has dazzled the observer in recent years. Since 1992, two-way trade has increased 200 times to the USD 60 billion target for the year ending March 2011. For two states that are often portrayed as rivals, this is nothing short of remarkable. But for all the euphoria about a globalised system, nation states still care about the relative effects of their economic interactions. The prudent ones learn the art of keeping their books balanced. India it seems has been doing neither, and especially, vis-à-vis China.

Beneath the veneer of embellished data lies an uncomfortable reality. India over the past five years has been drifting into a trading relationship that cannot be called anything but unequal. China is now India’s biggest source of imports, accounting for 11 per cent of its total imports. China also accounted for 18 per cent of India’s overall trade deficit last year.

Only an artist could paint the picture as one of ‘interdependence’. Today, India is probably the only Asian economy that runs a trade deficit with China. China’s other neighbours are running manufacturing surpluses, which are then processed and assembled in the mainland and shipped out to western markets.

To be sure, it would be far fetched to classify China’s relationship with her East Asian neighbours or vis-à-vis the West, as one of symmetrical interdependence. This is because a lot of the sophisticated R&D and high-tech components that go into China’s assembly factories continue to be manufactured in the US, Japan, South Korea or Taiwan or by MNCs from these economies operating in the mainland. Also since about 40 per cent of China’s exports flow to North American and European consumers, China’s current economic structure is, so far, dependent on the OECD economies (both at the supply and demand level). Nevertheless, China has carved out a massive FDI-funded enclave that has allowed an otherwise developing economy to plug into the manufacturing networks of advanced economies. If China pursues strategic policies, it will ultimately absorb the knowledge to build its own sophisticated industries.

India is altogether absent from these manufacturing supply chains that have connected the rest of East and South East Asia. Over the past decade, FDI in the Indian electronics sector has touched a paltry USD 750 million, underscoring India’s perceived un-competitiveness.

Now, let’s turn to the content and quality of trade between the two Asian powers.

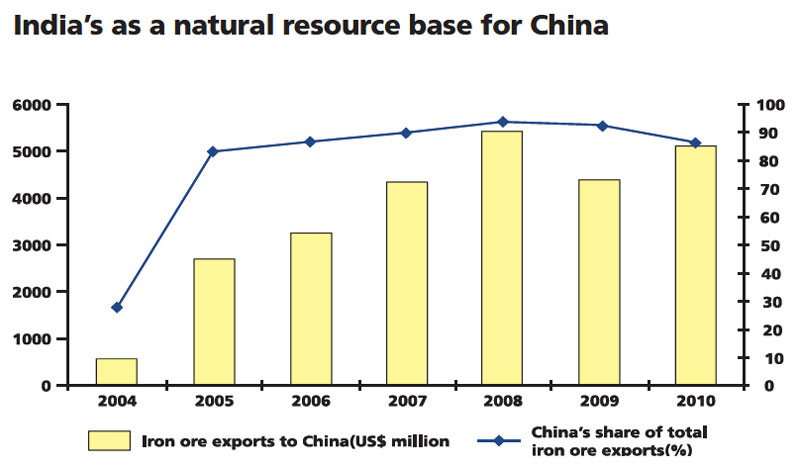

In terms of outbound merchandise, iron ore has been the top export item from India to China. Last year, iron ore accounted for USD 5.1 billion or 44 per cent of India’s total exports to China. Almost all of India’s iron ore exports go to China averaging around 115 million tons per year or around 25 per cent of China’s total iron ore imports.

There is no logical reason for India to be selling unprocessed commodities to steel manufacturers in China or anywhere. That the Indian state receives next to nothing for the limited natural resources that are leaking from India (iron ore prices have ranged from USD 60-180 per ton since 2007) makes this even more appalling. And to top it all, India imported USD 1.3 billion worth of iron and steel from China, which was 16 per cent of its total iron and steel imports last year.

The Karnataka Lokayukta, the anticorruption organisation, report on illegal mining is instructive. At an export price of Rs 7,000 the state was receiving Rs 27 in royalty. That is a royalty rate of 0.39 per cent! Lokayukta estimated that the total cost for an iron ore exporter would not exceed Rs 427 per ton giving the miner a 94 per cent profit margin. For India, this lost revenue could have been dedicated to the welfare of the displaced tribal population, for improving rural infrastructure in the resource rich regions of India, and perhaps even investing in R&D in the steel industry.

What does India import?

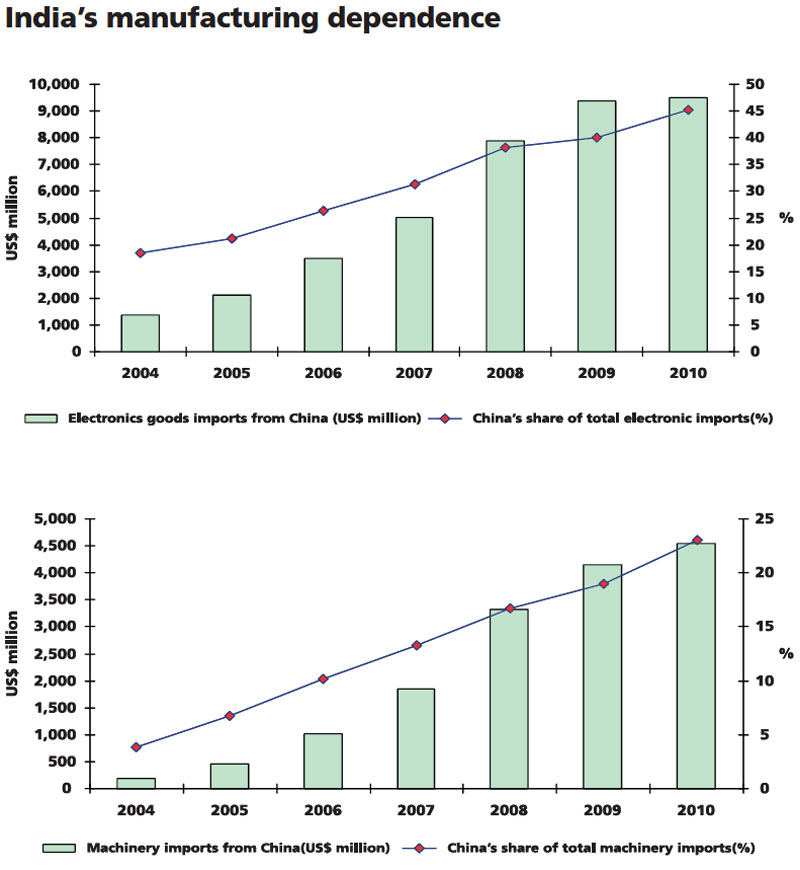

Electronic goods top the list of imports from China. Last year, China exported USD 9.4 billion of electronic products, which was also 45 per cent of India’s total electronic imports. If the current trend persists, by 2012, India would import USD 16 billion or 55 per cent of its total electronic imports from China.

The second largest category of merchandise from China is machinery products. Last year, India imported USD 4.5 billion or 23 per cent of India’s total machinery imports. One in four new powers plants in India currently rely on Chinese equipment.

Clearly, India qualitative and quantitative trade balance with China has been deteriorating for the last six years. But the blunt truth is that India’s economic relationship with China is a reflection of its distorted domestic economy. Indeed, India recorded a merchandise trade deficit of over USD 115 billion last year, suggesting the problem lies at home.

So why does India’s manufacturing sector lag behind its emerging markets peers? Large scale manufacturing, especially in labour-intensive industries, is underpinned by fundamental prerequisites that apply to most successful manufacturing locations: a basic literacy in the workforce upon which further skills can be imparted, physical infrastructure (like power, roads, railways and access to ports), access to financial capital, and crucially state policies that encourage the allocation of resources toward export-oriented manufacturing. And because all these structural attributes are lacking in India’s case, it does not receive the quantum and type of FDI that the rest of Asia has witnessed over the decades. According to a FICCI study, from 2000 to 2008, India received an average of USD 3.4 billion of manufacturing- oriented FDI sector each year. During the same period, China pulled in USD 40 billion of manufacturing FDI each year.

In contrast, India’s services sector has performed relatively better because it had access to the nation’s small pool of qualified workers and did not require too much physical infrastructure. Thus, while India’s share of services in overall GDP has increased from 37 to 49 per cent in the last two decades, the share of manufacturing has remained nearly frozen at 16 per cent. In contrast, according to a recent Assocham study, China’s share of its manufacturing sector to GDP is 35 per cent; South Korea, Malaysia and Indonesia’s is 30 per cent; Argentina and Brazil’s manufacturing sectors contribute 24 per cent to their national economies. But since services, which inherently require a skilled workforce, cannot absorb the majority of the ‘youth bulge’, the burden of job creation will always fall upon the manufacturing sector. This developmental pattern has been repeated in all historical cases: the rise of the European great powers, United States at the turn of nineteenth century, Russia in the first half of the twentieth century, East Asian tigers after the Sixties, Japan in the Eighties, and China in recent times. All these economies demons trated manufacturing growth that restructured the erstwhile agrarian polity.

India’s low-end manufacturing — the type that can provide jobs to millions of India’s unskilled labour force — has become so inefficient that as the Economist recently notes “it is currently cheaper to export plastic granules to China and then import them again in bucket-form, than it is to make buckets in India!”

The same could probably be said for organic chemicals, steel and a variety of processed commodities. No wonder Indian iron ore is being dumped into ships that transport it to China’s humungous steel industry. China’s steel output capacity exceeded 700 million tons in 2009, with a production of 568 million tons of raw steel that year.

Despite all the systemic weaknesses in India, there are a few countermeasures that can address the economic imbalance with our neighbour: First, if natural resources are going to be unwisely exported, a reliable system of collecting royalties supplemented by an export tax must be erected to re-alter the perverse incentive structure that prevails in the mining industry. Second, diversifying our export basket by pushing for greater market access in China in sectors where India Inc. claims it is competitive — pharmaceutical, ITES, higher-value engineering products etc. If China’s telecom hardware companies like Huawei and ZTE can earn USD 3.5 billion and USD 2 dollars respectively in revenues (2010 estimate) in the Indian market alone, surely we can use that to leverage reciprocal advantages for Indian companies in the mainland. Third, focus on manufacturing R&D: according to the ministry of science and technology, India spends an irrelevant USD 100 million (1.4 per cent of India’s total R&D spending) a year on research in electrical and electronics sector. Fourth, link Chinese FDI to tie-ups with Indian state and private sector firms (a practice followed scrupulously in China) and create conditions for technology transfers and job creation.

Finally, it is important to realise that China’s manufacturing juggernaut is buttressed by massive implicit subsidies in the Chinese economic system that have lowered the opportunity cost of the major factors of production — the value of the yuan, financial capital, electricity, transport infrastructure, natural resource use, labour costs etc. Competing with such a system requires a combination of superior innovation and strong public policy support for labourintensive manufacturing sectors, and a commitment to address India’s infrastructure woes.

The consequences of not addressing these structural challenges should be obvious. India’s dependence on China for electronic, machinery and telecom equipment is already overwhelming. The ultimate irony is that India by running stubborn trade deficits and transferring its limited natural resources to China is helping China create surpluses — that unlike vis-à-vis the west are not recycled into US debt — but diverted to social and physical infrastructure investment or perhaps even to its expanding military budget!

India’s current discourse over its economic relationship with China is nothing short of self-deception. To correct course, we need to recognise the problem. Is anybody listening?

(The writer is a research fellow at the Centre for Policy Alternatives and coauthor of Chasing the Dragon: Will India Catch up with China?)

Also Read:

Ghost of ’62

Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high

Also Read:

Reaching Tawang

Visitors must be baptised by rain, landslides and blinding fog

Also Read:

Defending Tawang

A limited war will not be to China’s advantage

Also Read:

The Spy Ring

India following China’s art of cyber warfare to give shape to an IT infrastructure setup

Also Read:

Debates and Delusions

Military build-up in Tibet provides China with multiple strategic advantages

Also Read:

War for Water

Water may turn into a defining bilateral issue

Also Read:

My First Responsibility is to Ensure that the Men Under my Command are Physically Fit and Battle-worthy

General Officer Commanding, 5 Mountain Division, Major General Anil K. Ahuja, VSM

Also Read:

Border Lines

BRO is the best and cheapest organisation for road-building in difficult terrains

Also Read:

Aerial View

Role of air power in India-China relationship