How Defence Services’ Staff College, Wellington, serves only a glass half full. An Extract

August 2017 marked the 70th anniversary of U.S.-India diplomatic relations. Ironically, the first five decades of the relationship between the world’s two largest democracies were marked by barely disguised hostility and estrangement because of India’s foreign policy of nonalignment and the United States’ Cold-War-based embrace of Pakistan. However, in the past two decades, four U.S. presidents from both political parties have identified India as a key strategic partner in Asia, resulting in a sharp downturn in U.S.-Pakistan relations and a concurrent upturn in U.S.-India relations.

August 2017 marked the 70th anniversary of U.S.-India diplomatic relations. Ironically, the first five decades of the relationship between the world’s two largest democracies were marked by barely disguised hostility and estrangement because of India’s foreign policy of nonalignment and the United States’ Cold-War-based embrace of Pakistan. However, in the past two decades, four U.S. presidents from both political parties have identified India as a key strategic partner in Asia, resulting in a sharp downturn in U.S.-Pakistan relations and a concurrent upturn in U.S.-India relations.

Washington’s strategic bet on India reflects a U.S. perception of converging strategic interests in promoting global and regional security, offsetting China’s growing military and economic power in Asia, and protecting the sea lanes running through the Indian Ocean. This requires a capable Indian military establishment. But does one exist, and what can be expected from it in terms of war-fighting capability, influence on regional stability, and impact on Indian government decision-making? Indian government restrictions on official U.S. contacts with Indian military personnel have limited our understanding of these issues.

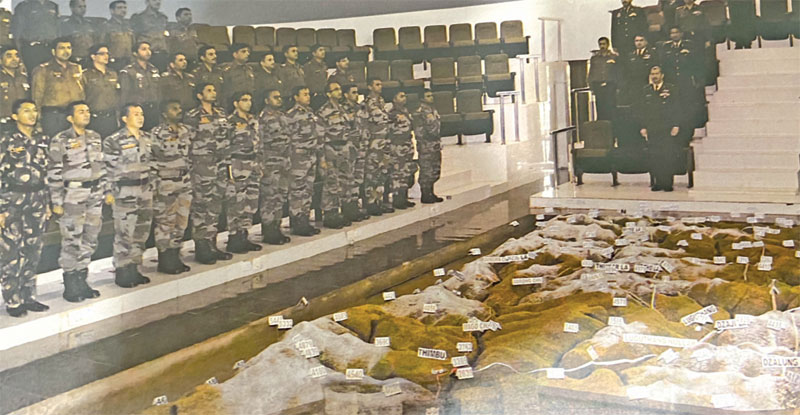

In an effort to fill some of the resultant U.S. information gaps, this study examines the observations of U.S. military personnel who attended India’s Defence Services Staff College (DSSC) at Wellington. Although the DSSC is a tri-service professional military education institution, this study focuses primarily on the Indian Army, the largest and most influential military service in India. Collectively, U.S. personnel at the DSSC had sustained interactions over an extended period of time with three distinct groups of Indian Army officers: senior officers (brigadier through lieutenant general), senior midlevel (lieutenant colonel and colonel), and junior midlevel (captain and major). The study focuses on the attitudes and values of the Indian Army officer corps over a 38-year period, from 1979 to 2017, to determine if there was change over time, and if so, to understand the drivers of that change.

Key findings of interest to the policy and intelligence communities include the following.

- The DSSC provides an adequate midcareer-officer education, but the college’s approach to pedagogy sharply restricts useful learning and inhibits the development of critical thinking.

- Indian students at the DSSC are highly nationalistic, but do not display the type of Hindu nationalist ideology known as Hindutva. The high level of social cohesion evident within the Indian military establishment seems to limit the potential for factionalism based on religion, ethnicity, or social class, and there is no indication that traditional democratic and secular values within that establishment are threatened.

- From a U.S. perspective, the ground doctrine taught at the DSSC pays insufficient attention to combat support and combat service support functions, and fails to adequately address combined arms operations. More importantly, it fails to provide effective joint training.

- Despite two decades of increasingly close U.S.-Indian political and military relations, a high level of mistrust (and thinly veiled hostility) about the United States generally persists in all three groups of Indian officers.

- The intensity of Indian Army hostility toward Pakistan increased in every decade of the study. Although China is perceived as India’s major long-term security threat, there is reluctance to characterize it as an enemy.

- Despite a deep-seated conviction that its internal security doctrine is effective, the Indian Army has yet to completely quell any of India’s four long-running insurgencies.

- The Indian Army ignores its own counterinsurgency doctrine in Jammu and Kashmir, and the extrajudicial killing of militants is an unacknowledged feature of that doctrine.

- Indian students at the DSSC were observed to be consistently apolitical in all four decades of the study, but the post-independence Indian civil-military relationship is evolving as a result of increasing internal and external security challenges. There is growing frustration with the government’s unwillingness to reform the Higher Defence Organization.

- Despite a doctrinal assumption that Pakistan will employ nuclear and chemical weapons against India in a future war, the DSSC curriculum avoids any significant discussion of the effects of these weapons, and no meaningful training. The Indian Army appears unconcerned about the efficacy of Pakistani tactical nuclear weapons and totally unprepared to operate in a nuclear environment.

The implications of these findings are mostly negative for South Asian regional stability for the following reasons.

Despite the official rhetoric of both governments and burgeoning military sales, other inherent friction in the relationship makes it unlikely that the United States and India will become genuine strategic partners in the foreseeable future.

The actions of the Indian Army in Jammu and Kashmir and the abrogation of the erstwhile state’s constitutional autonomy by the Modi government have accelerated the radicalization of a new generation of Kashmiri youth, rekindled an indigenous militancy once thought to have been defeated, and raised the level of violence along the Line of Control to levels not seen since 2003.

In the event of a future war with Pakistan or China, the Indian Army may not perform as well as it expects, and a failure against China might draw in the United States on India’s side, with the attendant risk of horizontal military escalation in Asia.

In the event of a future war with Pakistan or China, the Indian Army may not perform as well as it expects, and a failure against China might draw in the United States on India’s side, with the attendant risk of horizontal military escalation in Asia.

There is no reason to expect that, in any future war with Pakistan, India will understand Pakistan’s nuclear “red lines” or that the Indian armed forces will not inadvertently cross one or more.