Reporting the Israel-Palestine conflict has always been fraught with danger. An extract

Shyam Bhatia

Israeli immigration and special security were especially tough at Ben Gurion airport at Tel Aviv and the three overland crossings—two from Egypt and one from Jordan. Most foreigners coming into Israel register their surprise at the sometimes lengthy questioning they have to undergo. This questioning may be tougher still for international reporters who have Arab stamps in their passports and/or with some further connection to the Arab, Asian and Islamic worlds. Many of them are automatically labelled potential suspects by the young security guards who are changed at border crossings every three of four months.

Israeli immigration and special security were especially tough at Ben Gurion airport at Tel Aviv and the three overland crossings—two from Egypt and one from Jordan. Most foreigners coming into Israel register their surprise at the sometimes lengthy questioning they have to undergo. This questioning may be tougher still for international reporters who have Arab stamps in their passports and/or with some further connection to the Arab, Asian and Islamic worlds. Many of them are automatically labelled potential suspects by the young security guards who are changed at border crossings every three of four months.

One Asian colleague loved to tell the dinner table story of how on one occasion he was stopped and interrogated for two hours when he tried to cross over from Sharm el-Sheikh into Eilat. Before he knew it, he was surrounded by heavily armed guards who marched him into an interrogation room where he was first stripped and then questioned for the next two hours. As a result he missed his connecting Arkia flight to Tel Aviv.

The following day when he returned to Eilat airport, he handed in his new ticket and started taking of his clothes. Fellow passengers and the woman at the check-in desk watched in horror as he took off his shirt, his trousers, his socks and his shoes. All he was left wearing were his freshly laundered underpants. As the check-in clerk screamed in horror, ‘What are you doing?’ he responded calmly and without any hysterical outburst, ‘I’m saving you some of the trouble in advance because I don’t want to miss today’s flight as well’.

The security experienced by both arriving and departing passengers at airports like Eilat and Ben Gurion was sometimes just as great or even greater on key roads leading out of the major cities.

On one occasion the road from Jerusalem to the West Bank city of Jenin was like a still picture from the Second World War. There were no tanks in sight, no Eisenhower or Churchill, but Israeli army jeeps were abundant, driving at speed, clogging every intersection. What the Palestinians call the ‘stone’ Intifada or uprising was at its peak and the Israelis were at a loss over how to stop it. By then they had tried every trick in the book to somehow end this popular uprising.

In April 1988 they dispatched an elite commando unit to Tunisia to assassinate the man they believed was the mastermind and driving force behind the riots. Khalil Al Wazir, known to his followers as Abu Jihad, or the father of holy war, was working in his Tunis office late at night when the commando group surprised him shortly after midnight. Israel’s future defence minister, Moshe Yallon, pet name Bogy, was commander of the group that stormed the villa and peppered Abu Jihad with machine gun bullets.

The killing of Abu Jihad did not stop the Intifada. On the contrary, it added more fuel to the fire and even encouraged the rise of endless new militant groups among the Palestinians living in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

One of these groups, the Black Panthers, began operating in the district of Jenin, in the northern tip of the West Bank. They consisted of dozens of young Palestinian militants who’d decided the stones and petrol bombs were no longer enough. Always masked and dressed in black, they preferred M16s and Uzi submachine guns.

One of the group’s founders, Ahmed Abu Awad, from the town of Qabatya, sent his men to ambush Israeli soldiers, and kill any Palestinians suspected of collaborating with Israel. Scores of Palestinians were killed on his orders. (Ahmed Abu Awad himself was subsequently captured and later released as part of a peace deal.) For their part the Israelis devoted enormous energy and technology to try and break the Panthers. But the Israeli army were not the only ones looking form them.

Western journalists also had the Panthers on their radar. When I was offered the rare opportunity to meet leading members of the group, I didn’t hesitate. Friends warned me of the obvious risks and dangers. One, a Palestinian called Khaled, asked, ‘What will happen if the Israelis turn up? You could get caught in the crossfire.’ His warning proved to be uncannily accurate.

After paying a few hundred dollars to a local contact in Jenin, ‘Samir’ agreed to escort me to the remote mountainous village of Kufr Rai, south of Jenin town.

The local population then was less than 2,000 and the narrow access to the village was paved with hundreds of ancient olive trees. I was told some were nearly 2,000 years old.

In the village centre outside the mosque, Samir and I were greeted by three men. They invited us into a nearby house where an elderly woman dressed in traditional black and red robes served us black tea laced with mint leaves.

Samir and the three men were whispering among themselves. It was impossible to hear what they were saying, but I assumed they were arranging the details of the forthcoming meeting. Half an hour later we were standing on the balcony when someone kicked open the metal front door. These must be our militants, I remember thinking, as a thin, dark man dressed in army fatigues and t-shirt with an M16 swinging from side to side rushed to where we were standing. ‘Everyone sit down,’ he shouted in Arabic. ‘Don’t move.’ As he shouted, another six men followed, similarly brandishing their own M16s.

Before I could fully absorb what was happening, my new friend Samir leaned across and whispered, ‘jaish’ (army). To our shock, the men turned out to be members of the newly created and elite Israeli army unit, Duv Devan, which means cherry in Hebrew. Subsequently revered as one of the most prestigious counter terror cells of the Israeli army, they specialized in conducting undercover operations dressed as local Arabs. Their motto in those days was, ‘For by wise counsel thou shalt make thy war’ (Proverb 24:6).

By now I was convinced we were in serious trouble as the unit commander asked for our passport and ID cards. My Palestinian friends had gone white with shock. I managed to look out of the open window and saw the house was surrounded by five army jeeps filled with more soldiers, although these were dressed in conventional army uniforms.

As I produced my passport the commander looked at me with apparent astonishment, then smiled before asking, ‘Ah, British, what are you doing here?’

‘I’m a journalist doing my job and talking to local Palestinians’, I replied. He responded by asking, ‘Why here, what brings you to this particular village?’ I returned with, ‘Why, is this a closed military zone, have I broken any laws?’

The spontaneous interrogation stopped for a moment. Then the commander continued, ‘No, no, but do you have meetings with anyone in particular?’

At that moment I realized this was not just a routine raid or operation. Then I remembered the warning of my friend Khaled back in Jerusalem. He was all too accurate in assessing the risk I was taking in my search for the Black Panthers.

While I was disappointed that my planned meeting had not materialized, there was also some relief that the masked men—the men I so wanted to meet—were not actually present when the soldiers appeared. A firefight would almost certainly have ensured with me in the middle. The encounter with Duv Devan did not last more than twenty or twenty-five minutes. Soon after my interrogation, the commander went out to his jeep and telephoned his headquarters. Seconds later without a backward glance he and his men left in a cloud of dust.

By now it was obvious that any hoped-for meeting with the Panthers would not take place. As we drove from the village to Jenin town centre, Samir asked, ‘Do you realize that the Panthers were in the house next to us? They were lucky they did not show themselves earlier, or they would have been killed and we might have died as well. But don’t worry, if we come back in a few days, I will arrange another meeting.’

One week later I finally managed to interview two Black Panther ‘commanders’ Ahmed Daka, nicknamed El Kikh, and his deputy, Amin Rahhal. Both in their mid-twenties and reasonably well educated, they met me in the village of Arr Rabeh, a ten-minute drive from Kufr Rai. This time there was no Israeli army patrol to interrupt us. Throughout my thirty-minute interview we were surrounded by their helpers who kept a constant and nervous look out for any hostile forces nearby.

During our meeting I could not help remembering what had happened a week earlier. It was a dangerous time—yet again—but I was determined not to let this opportunity of an exclusive with the Black Panthers slip by.

Not all my journalist colleagues were as fortunate. The Black Panthers were elusive and mistrusting. Many promised interviews with the foreign media simply failed to materialize. As for Daka and Rahhal, they were ambushed and killed a year later in 1992.

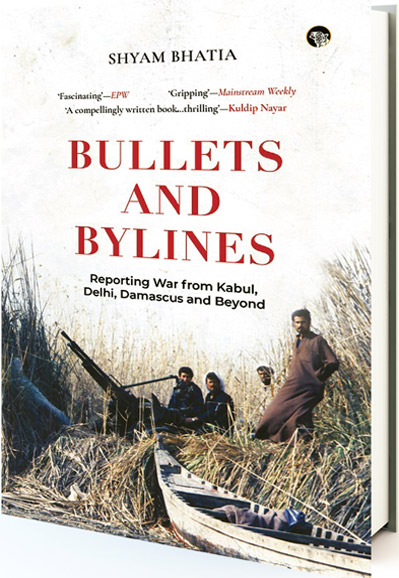

BULLETS AND BYLINES: REPORTING WAR FROM KABUL, DELHI, DAMASCUS AND BEYOND

Shyam Bhatia

Speaking Tiger, Pg 248, Rs 499