What art tells us about popular narrative in the years leading up to independence. An extract

Vinay Lal

Vinay Lal

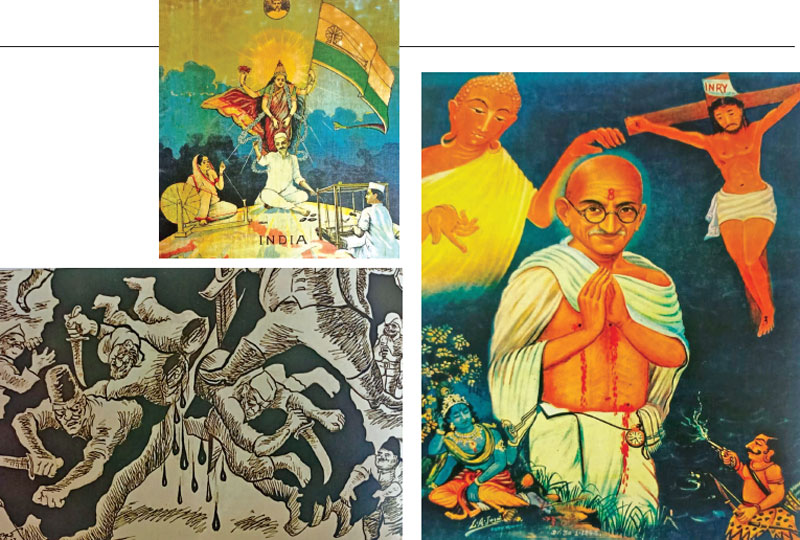

The martyrdom or shahadat—an idea foreign to Hinduism as such—of Gandhi has been one of the principal subjects of Indian art. Nathuram Godse, let me be bold enough to say, let go off his unacknowledged Muslim self that he had been hosting for so long as if in homage to the very partition of the country that he deplored and for which he felt that the Mahatma had to pay the price. Less than six months before his fatal deed, India had gone through the most cataclysmic upheaval in its modern history. At least a few of the world’s leading photographers, among them Margaret Bourke-White, Sunil Janah, and Henri Cartier-Bresson, were fortuitously at hand to photograph the wrenching scenes bequeathed by the Partition or batwara of India. Some of the images they captured cannot be shown to modern viewers without a warning, advising them of the graphic contents, given the contemporary commonsense about sensitivity to the feelings of others, the societal impulse to steer clear of ‘offense’ and the ease with which we are ‘traumatized’. However, the violence had commenced some months before the Boundary Commission had completed its task and the country was bifurcated, and Chittaprosad had seen or heard enough that in March 1947, he gave vent to his sentiments with a sketch that is at once lurid and bursting with ferocious energy: with daggers drawn, men lunge at each other, tearing apart chunks of the nation. Blood drips, but it could be the tears of a nation; a faceless overlord, a Rhodes-like colossus, hovers over them all. The horrors of the Partition were of a magnitude that India, at least, had not witnessed for some time, and contemporary artists like most common people at that time appear to have been numbed by the violence. For their part, printmakers projected Gandhi, Nehru, Maulana Azad, and Sardar Patel as the leaders into whose hands the country had placed its destiny. But six months into Independence, Gandhi was shot dead and, if we are to believe the printmakers, had joined the ranks of Jesus and the Buddha.

As a capsule summary, albeit one that is not likely to be encountered in school textbooks or even scholarly monographs, this may appear to furnish a broad picture that is not inaccurate even as it is perhaps idiosyncratic, for example in the heretical reading that I have suggested of Nathuram Godse’s personality. The idea that the assassin of Gandhi too had an ‘unacknowledged Muslim self’ will strike his acolytes and followers, whose numbers have been growing steadily in modern India, as preposterous, but it is inspired by the worldview of the Mahatma, for whom neither the Muslim nor the Hindu in India could be complete without the other. It is Sir Syed Ahmad Khan who, in an earlier age, is thought to have said that ‘India is a beautiful bride and Hindus and Muslims are her two eyes, but it was very much Gandhi’s view as well. Many of the official pronouncements in Pakistan, following Gandhi’s assassination on 30 January 1948, that the two countries had been emotionally united by his death may have been a rhetorical gesture on the part of a government aware of his immense stature throughout the world, but in India the effect of his death was electric. Not only was the communal violence brought to a halt, but the country was shocked into a deep and mournful silence. The long and distinguished career of the Indian artist Krishen Khanna practically began with his oil painting, ‘News of Gandhiji’s Death; apparently executed in the weeks after the killing (fig. 11.3). Under the dim light of a streetlamp, men and women stand in muted horror silently poring though the newspaper attempting to absorb the enormity of the calamity before a nation now plunged into darkness. They are united in their shock; yet, as the painting seems to suggest the fissures that had led to Partition and bloodshed remain and augur an uncertain future. Each person is looking down; they do not embrace each other as those who are bereaved commonly do so nor do they weep, unless the depth of their sorrow is beyond tears, pointing to the possibility that the collective sorrow of the nation may not be enough to transcend the boundaries that the Boundary Commission drew with such intense cartographic intent.

As a capsule summary, albeit one that is not likely to be encountered in school textbooks or even scholarly monographs, this may appear to furnish a broad picture that is not inaccurate even as it is perhaps idiosyncratic, for example in the heretical reading that I have suggested of Nathuram Godse’s personality. The idea that the assassin of Gandhi too had an ‘unacknowledged Muslim self’ will strike his acolytes and followers, whose numbers have been growing steadily in modern India, as preposterous, but it is inspired by the worldview of the Mahatma, for whom neither the Muslim nor the Hindu in India could be complete without the other. It is Sir Syed Ahmad Khan who, in an earlier age, is thought to have said that ‘India is a beautiful bride and Hindus and Muslims are her two eyes, but it was very much Gandhi’s view as well. Many of the official pronouncements in Pakistan, following Gandhi’s assassination on 30 January 1948, that the two countries had been emotionally united by his death may have been a rhetorical gesture on the part of a government aware of his immense stature throughout the world, but in India the effect of his death was electric. Not only was the communal violence brought to a halt, but the country was shocked into a deep and mournful silence. The long and distinguished career of the Indian artist Krishen Khanna practically began with his oil painting, ‘News of Gandhiji’s Death; apparently executed in the weeks after the killing (fig. 11.3). Under the dim light of a streetlamp, men and women stand in muted horror silently poring though the newspaper attempting to absorb the enormity of the calamity before a nation now plunged into darkness. They are united in their shock; yet, as the painting seems to suggest the fissures that had led to Partition and bloodshed remain and augur an uncertain future. Each person is looking down; they do not embrace each other as those who are bereaved commonly do so nor do they weep, unless the depth of their sorrow is beyond tears, pointing to the possibility that the collective sorrow of the nation may not be enough to transcend the boundaries that the Boundary Commission drew with such intense cartographic intent.

Oddly enough, the state funeral for the murdered ‘Father of the Nation’ became one of the gravest responsibilities of the nation just months after independence, and the responsibility for an undertaking of that magnitude was assigned by the new government headed by Jawaharlal Nehru to the army. The art of the time does not invite us to reflect on the irony of deploying the armed forces of the nation to lay to rest the supreme exponent of the idea of nonviolent resistance. It is directed rather towards several other ends-none more so than the assassination of Gandhi and, most strikingly, his apotheosis as a religious leader akin to Jesus and the Buddha and as an avatar who could be reasonably placed alongside Krishna and Rama. In the immediate aftermath of the assassination, we can also see the evolution of what I have simply called ‘the biographical print’ and what Christopher Pinney has tantalizingly characterized as the ‘avatar’ print. Finally, in concluding this discussion, I suggest that printmakers were keen to project a firm idea that even with Gandhi’s passing, the country was in good hands. Just who would be the custodians of the country’s future had become clear during the course of the freedom struggle and particularly during the negotiations that preceded Independence, and artists sought simultaneously to establish a continuity with the past, project the advocates of freedom such as Subhas Bose as similarly worthy occupants in the nation’s pantheon of revered martyrs, and assure the people that Nehru, Sardar Patel, and Maulana Azad governed with Gandhi’s own blessings. If Gandhi himself had become synonymous with India—astonishingly, as early as 1920 as one printmaker suggests—or in a fashion represented the totality of an India that in turn is represented cartographically, then those upon whom the mantle of his legacy had fallen could likewise be seen as embodying amongst themselves, the soul of the country.

INSURGENCY AND THE ARTIST: THE ART OF THE FREEDOM STRUGGLE IN INDIA

Vinay Lal

Roli Books, Pg 260, Rs 2,160