How the presence of a US citizen saved 3,000 CAR citizens from a massacre. An extract

Anjan Sundaram

Bouca’s restaurants were shut. And we were about to cut up a few tomatoes, bananas, and mangoes for dinner, when Angeline invited us to dine with her and the doctors, in a room reserved for the nun’s guests.

Bouca’s restaurants were shut. And we were about to cut up a few tomatoes, bananas, and mangoes for dinner, when Angeline invited us to dine with her and the doctors, in a room reserved for the nun’s guests.

The Doctors without Borders team leader was a Quebecois surgeon named Berthier. “Hassan is high on ketamine,” he told me.

I asked what that was.

“A white crystal stimulant that makes him manic.”

Berthier had tried to save Hassan’s former commander, James, who the rebels had shot in the liver some weeks before. At one point, James had looked up at Berthier, and said, “Doctor, I think I’m going to die.” Berthier said, “When people have that premonition, death is very close.” He had then only diminished James’s pain. It was like a missionary’s work.

The church staff had laid out a buffet of salad, boiled vegetables, pasta, and a fish. We ate behind a closed door, away from the gaze of the hungry people in the yard. Angeline said benediction. “The soldiers killed 180 the last time, and even the Pope could not stop them. Give us courage for tomorrow.”

The church’s gates creaked. Men crept out carrying their bags. But the majority of people here behaved as if Hassan had not come by that morning. They cooked their meals and rinsed their plates, which they stacked up neatly for use the next day.

On my post-dinner walk through the grounds, I met a mother who asked me for medicine. “My nine-month-old girl Mirabelle has a fever,” she said. I gave her half a paracetamol tablet, and asked why she stayed.

“Soldiers have burned our homes and the bush,” she said. “I have nowhere left to hide. They also burned my peanut crops.” A gust blew into the camp. And she shook her head. “That noise of the leaves reminds me of hiding in the forest. The soldiers hunted us down like animals.”

Vendors sold beignets—balls of fried dough—at food stall. A man waiting in line in front of me said that a few weeks before, Hassan had beaten up Angeline. “He bruised her so badly that the church transported her to a hospital in Bangui.”

Angeline had served as a human shield, putting herself between the soldiers and the people. In a conflict with few escapes, in which people retreated into the jungle, Angeline offered them refuge in this church. And this place had a natural power. People in distress looked to God.

To calm the children, the doctors perched a laptop on a low wall and played a science fiction movie. The children watched rapt, sitting cross-legged on the ground. The movie was about an extraterrestrial colony, another world, which made us forget the next morning. Angeline’s figure paced the church’s foyer. The camp became quiet at midnight. People slept in tents and under makeshift straw roofs.

A soft light shone on the garden and made beautiful silhouettes of the bushes and their leaves. It was the cabin light from our 4×4. Hamida sat at the steering wheel. I thought he tried to escape. But he was shirtless, and thumped his chest forward and back. I rapped on the window and startled him. He rolled down his window. Hip-hop music blared from the speakers.

“You’re going to drain our battery,” I said. I reached over to the radio and turned it off. The bottle of tobacco lay at his feet. I dragged him out of our 4×4 and confiscated its key.

“Go to bed,” I said, and followed him to our room.

He made to lie on the floor.

I pointed him to the bed.

“And you?’’ he asked.

I said, “We need you sharp tomorrow.”

I stood at the porch and listened to the crickets chirp.

My feet cracked the dried leaves. People snored. At one tent I heard a shuffling and then quiet, and saw inside the form of someone sitting up. I had disturbed them.

A shadowy figure walked in circles near where the movie had played. It was a Greek nurse form the Doctors Without Borders team. He held a can of beer from the doctors’ supplies. “Welcome,” he said, looking relieved. He pulled up a chair and poured some beer into a second cup.

He was slim, and his face was covered in stubble. He said looking nervous, “This is my first mission.” He otherwise worked in a Greek hospital.

“I want to buy an apartment on a Greek island,” I said. “As a place to write.”

“The sea,” he said, smiling.

We spoke of my dream of the apartment, as though it were imminent. It calmed us both.

“I found some good prices in Lakonia.”

“Don’t go there, they don’t like people like us.” He was gay.

“You should find a room with white stucco walls and a view of the Aegean,” he said “Skopelos is a good island.” I wrote the name in my notebook, and over our final sips of beer, promised to buy a place there and invite him over. It was 2:00 a.m.

I didn’t turn on the lights, so I couldn’t tell who was asleep where. I lay on the floor.

There was a knocking.

I shone my flashlight at the door. Lewis stood still.

“I got their attention,” he said.

“You did what?”

He had called the Human Rights Watch office in New York using his satellite phone and told them about the massacre at 8:00 a.m.

I said, “Let’s talk in the hallway. The guys here are asleep.”

Human Rights Watch had brought Bouca to the attention of the White House, the United Nation Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, and the Elysee, the French president’s office. The embassies had refused to intervene. But Human Rights Watch now had an employee here. Lewis’s presence had suddenly made this church important.

I said, “How will they contact the soldiers here?”

“I don’t know,” he said.

“They wouldn’t know the commanding officer’s name.”

“Let’s sleep, man.”

Lewis lay on the floor beside me. I couldn’t shut my eyes.

He kept turning.

I consoled myself thinking of home.

Acadia came to me: its rugged cliffs on its beaches and at Miscou Island, where the sea was dark. I remembered lying in bed with Raphaelle, our room smelling of her sweet breath. That night, the waiting emptied me.

I got up at around 6:00 a.m.

I had heard baritone voices in the yard, and the clangs of casseroles. A child cried. I dressed myself and stepped out into the morning chill. Women had started to smash corn in their pestles for lunch.

The church’s bell tower was obscured by mist. I grabbed a bottle of water from our 4×4’s boot and chugged it. The doctors lined up against the whitewashed building, and Angeline waited in the garden, beside a statue of Virgin Mary.

The women pounded, as if counting the time. At 7:35 a.m. the soldiers began shooting at our compound. Bullets smashed into the church’s walls. Still, the women pounded their pestles. The gunfire stopped. A lone shot rang out. Another. The people became restless and moved backward, toward Angeline, anticipating a mortar bomb.

Someone outside shouted at us, “Open the gate!” They banged on the metal.

A man in the churchyard shouted back. They started to converse.

We waited inside our 4×4.

“Maybe it’s time to leave,” I said

Lewis said we couldn’t. “Not until the peacekeepers get here.”

I said, “What peacekeepers?”

“The White House is arranging everything.”

A doctor passed by our vehicle. I told him, “We’re safe! The attack has been called off.” He hurried away, and soon Angeline arrived. “You know what is happening?” she said.

“The White House called up Bangui,” Lewis said. The United States government had warned Hassan that Lewis should not be harmed under any circumstances. Since Lewis was located inside the church, Hassan could not attack.

A United Nations battalion had been ordered to move to this church from the nearby city of Batangafo. Once it arrived, we could leave Bouca, without the risk of triggering a massacre.

So Lewis’s presence here had saved the three thousand people who waited in the churchyard. But he had achieved this by exposing the cruelty of our world. Three thousand Central African lives were worth less than one American life.

Angeline had watched helpless as nearly two hundred people were massacred three months before. “I thought nothing could be done for them,” she said. “But for you?” Lewis had reopened her wounds. He had proved that the people here could be protected—the mechanisms and powers existed, but the world had to consider Central African lives as worth saving.

Lewis clenched his fist. “We did something good,” he told Angeline. “We saved these people.”

“It’s true,” I said, wanting to support Lewis in this awkward moment. Angeline and the doctors stared at him and left.

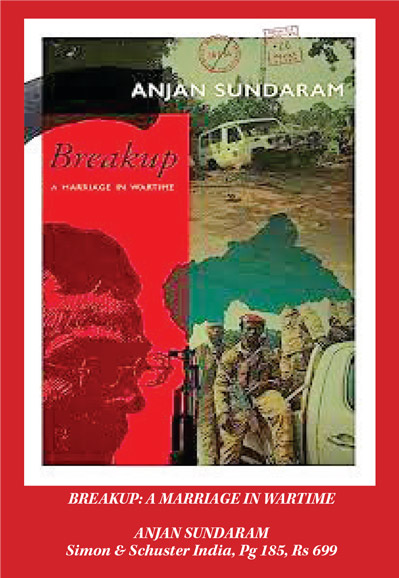

BREAKUP: A MARRIAGE IN WARTIME

Anjan Sundaram

Simon & Schuster India, Pg 185, Rs 699