With each day the solution is becoming difficult

Pravin Sawhney and Ghazala Wahab

Sahib in Srinagar

Srinagar: Perhaps, it is in the nature of the conflict or politics that Kashmir runs out of neither surprises nor its own logic. Conflicting opinions, turnarounds, warnings, threats, optimism, complacency, everything comes with its own irrefutable logic, and of course surprise. The ebb and tide of street protests, violence and peace follow their own course with neither great provocation nor believable reassurance. And so, it was only to be expected that the summer of 2012 would not be a repetition of any summers gone by.

This one seems to be the season of sacrilege. The first to throw the stone at the holy cow was Hurriyat (M) leader, Professor Abdul Ghani Bhat, who by publicly questioning the validity of the UN resolutions on Kashmir in early May, threw the splintered-Separatist fraternity into further camps. Some asked him to retract his statement, others called for his expulsion. Even as Bhat revelled in rattling others, his party leader Mirwaiz Umar Farooq struggled with his response, before settling for the safest, though lamest reaction. He said, “In a democracy everyone has a right to say what they want to.”

Meanwhile, defending his statement, Bhat says, “I don’t mind if people think that my statement is a climb-down. I think I deserve kudos for finally accepting the ground reality; for moving from idealism to pragmatism.”

Another separatist leader, though not officially a member of Hurriyat (and thereby a relatively independent activist), Sajad Lone, having tasted the bitter electoral pill in 2009, is once again openly sharpening his fangs for the state assembly elections 2014, where he is hopeful of drawing blood if not upsetting the apple cart completely.

Nursing a hangover induced by night-long campaigning-cum-motivational session with wet-behind-the-ears party cadre, drawn from universities and junior bureaucracy, Lone says, “Big heads will roll in 2014. Even if we do not get too many seats, we will have an important say in the government formation.” Would he consider joining the coalition government if invited to in 2014? “I might,” he says, before adding quickly, “But what would really make a difference is if people like Mirwaiz take the plunge in electoral politics. For far too long, Jammu and Kashmir has been ruled by two families, the Abdullahs and the Muftis. We need new faces in the state; we represent the change.”

After 22 years of brutality, violence, deaths and disappearances, has life come full circle to where it all started — the rigged assembly elections of 1987? Not quite. A senior J&K bank officer, who does not want to be named for obvious reasons says, “Non-Kashmiri people make a mistake when they read too much into everyday occurrences or statements made in the state. As a Kashmiri, I can say with authority and personal experience that Kashmiris have no conviction. Our mind is like mercury, it quivers all the time and rolls in whichever direction pressure is applied.”

Completing the quadrangle of so-called blasphemous views, the fourth one comes from the serving Congress minister in the state government, Taj Mohiuddin, responsible for Public Health Engineering (PHE) and Irrigation & Flood Control. Blaming Pakistan-sponsored terrorism for all the ills of Kashmir, he says, “The Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) is a non-issue. Only vested interests raise it from time to time.” In an allusion to Mumbai 26/11 he says, “One must realise that even 10 militants can hold the city to ransom.” The fact that his own chief minister has been raising this issue from time to time is of no consequence for him. He dismisses that as chief minister’s personal viewpoint with which he does not agree.

Yet, despite the certainty of their divergent views, uncertainty of the ground situation unites them. As Mohiuddin says, “In this Valley, rumours travel faster than light. One does not even need an incident to trigger violent reaction among the people. So, we all keep our fingers crossed. I can only pray that nothing happens.” With all the fingers crossed, quips a senior police officer, none will be able to throw stones; so at least the crossed fingers will ensure peace. If only peace came that cheap.

Summer 2012

For the last few years, every summer has been breaking the record of tourist numbers to the Valley. This year also, the record has been shattered many times over. In fact, domestic tourists started flocking to the state even before the season officially commenced, leading one hotelier to comment that there is no ‘season’ in Kashmir any longer, tourists come all year round. The only thing that deters them is violence or fear of violence. Hence, summer 2012 seems to be reaping the peace harvest of 2011. Such is the tourist traffic, that a large number of private residences have been converted into guest houses to accommodate those who have not been able to find hotels or houseboats.

“Apart from accommodating the tourists, this is also giving an opportunity to both, the visitors and the hosts to see and understand one another from close quarters,” says one bureaucrat. “Hopefully, this will dispel misconceptions on both sides and lead to better integration,” he says, ignoring the fact that national integration has never been an issue in Kashmir. For decades, Kashmiris have travelled, studied, lived and worked in as far-flung mainland cities as Goa, Calcutta, Bangalore and so on. Even today, most so-called Separatists politicians (in addition to regular business and service class people) have properties in cities like Delhi and Mumbai. Moreover, with Kashmir being the favourite holiday destination of rich Indians since the Fifties (who shunned small hill stations like Mussourie and Shimla for their more provincial status) and also of the Indian film industry, familiarity with the Kashmiri way of life, despite the romantic overtones, has never been in deficit. But in the absence of concrete measures to address the core issue, everything else is being passed around as a means of resolution.

Heralding the signs of growing normalcy, the state government has also urged the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) to make itself invisible, by removing its more conspicuous bunkers. As FORCE team drove through the city, there was visibly less khaki and more blue (of the traffic police) on the streets.

Finally, capping the so-called ‘normalcy’ was the carping of local environmentalists about the tourist pressure disturbing fragile ecological balance in the state. Having tired of the beaten Gulmarg-Pahalgam circuit, travellers as well as tour operators have been scouting for virgin territories this year causing some to protest violations of environmental norms. As if this was not enough pressure on the state infrastructure, the annual Amarnath pilgrimage is bringing in even more numbers, as pilgrims often combine pleasure with piety.

Given all this, it would seem the biggest issue in Kashmir today is management of tourists, as that is the subject on top of everyone’s mind. And why not, says inspector general (IG), (operations) CRPF, B.N. Ramesh, a few weeks before the commencement of Amarnath pilgrimage. “Every day, five to six thousand tourists are coming into Kashmir. Over one lakh (one hundred thousand) vehicles are going in and out of Srinagar daily, so this is what occupies us,” he says, adding, “We are expecting nine to 10 lakh pilgrims during Amarnath pilgrimage this year.”

What is bad for the ecology is good for the economy. Hence, not only are people not complaining, they have also resisted several attempts by a few to wreck the happy story by indulging in strikes or protests. “It is true that three consecutive summer protests from 2008-2010 sapped the energies of the people and eroded their earnings,” says a superintendent of police. “They neither have the desire nor stamina for more, especially when the alternative is so much more promising,” he says, quickly adding, “But the important point here is that we should not give them any reasons to think otherwise.”

Hence, as in 2011, this year also, the army, J&K police as well CRPF are organising a series of sporting competitions through the summer months, including in places like Sopore, to keep potential trouble-makers out of the reach of stones; handing them cricket balls instead. Yet, through all this are crossed fingers; because everyone knows that underneath the thin sheet of normalcy is a deep quivering morass.

Whose Normalcy Is It

“Every other year the authorities try to trumpet the return of ‘normalcy’, linking it with tourist traffic but then it all goes back to square one when an atrocity against civilians occurs,” says Aamir Bashir, Kashmiri origin actor and now a director of a film based on Kashmir, Harud (Autumn).

And as if on cue, just as the Amarnath pilgrims started to arrive in the Valley, signs of the fragility of this normalcy showed up. In the early hours of June 25, the 206-year-old shrine, Peer Dastgeer Sahib in downtown Srinagar caught fire. As often happens in India, fire tenders were slow to respond and even when they did arrive, they scrambled to find a source of water to douse the raging fire in the wooden structure that made up the shrine. By the time, the fire brigade got its act together, the shrine was gutted.

This could have happened anywhere in India. In fact, a few days before this, a section of the Maharashtra Mantralaya (Secretariat) was damaged in fire, supposedly destroying crucial documents pertaining to several corruption cases. While whispers abounded about a conspiracy, no one came out to protest. But in Kashmir, people distrust the government and security forces so much or alternatively, they are simply so angst-ridden, that people poured out on the streets indulging in their favourite form of protest — pelting stones — at the fire brigade and the assembled police personnel. Wild rumours spread about foul play and the crowd started to swell, forcing the police to resort to crowd control measures. Provocative statements were made blaming the fire on the government, the security forces and just about everybody. By the end of the day, 69 people were injured, including 30 police men. The fire tenders were also damaged.

If even one protestor had died, by accident or design, it would have been the end of the tourist season and the beginning of another cycle of protests. Perhaps fearing this, the police ordered restrictions on the movement of lay people in potential trouble-spots and also restrained a few Separatist leaders who could exploit the accident. Nothing can explain why the people should behave like this but Bashir suggests a sense of injustice over the years as a plausible reason. “It is deep-rooted in the psyche of the people, that the Indian state is not interested in administering justice in the state,” he says.

A senior IPS officer seconds this. According to him, even administrative normalcy (as opposed to normalcy following a political resolution) cannot return until there is residual resentment among the people. Not going too far back in history, he says, “If we only address the chasm caused by the 2008 economic blockade by the people of Jammu, we can make some progress.Unfortunately, while many people continue to deny that there was a blockade, those who do acknowledge refuse to see its destructive ramifications. The fact is, for the first time, there is a wide cleavage between Jammu and Kashmir. Even today, after four years, Kashmiri Muslims do not feel comfortable in Jammu.”

Even though the insurgency has been Kashmir-centric, there has been no blatant animosity between the two regions, except grievances of each region — Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh — that it gets neglected. This, despite the fact that the insurgency had very pronounced religious overtones right from the beginning, even if it was not as jihadist then as it is now. “All that changed in 2008,” says the IPS officer. According to him, it was primarily because of a difference in the way police reacted to protests in both regions; while there were only a handful of casualties in Jammu, in Kashmir they were huge and unnecessary. “Unfortunately, that is how our police force is,” says the IPS officer (who incidentally is not a Muslim). “There is a pronounced bias, which becomes evident when there is a comparison and adds to the feeling of otherness,” he says.

Bashir also alludes to the feeling of ‘otherness’ when he says, “The feeling of being treated like the ‘other’ by the state is very strong. Generations that have grown up post 1989 know no other way of viewing their world.” While it may still be a minority view, but the fact that religious fault-lines in the state are quite sharp now is evident in what Lone says. According to him, “The entire construct of the state of Jammu and Kashmir is artificial. Jammu has nothing in common with Kashmir or with regions like Rajouri, Poonch, Doda and Kishtwar. Jammu is closer to Punjab in ethnicity. If ever the situation comes, then the Muslims of Doda, Poonch, Rajouri etc will vote alongside the Muslims of the Valley.”

Hopefully, a situation pitching ethnicities and religious identities against one another would never arise in Jammu and Kashmir but there is no escaping the fact that with each passing day, a political resolution of Kashmir (which will be acceptable to all the stake-holders inside and outside the state) is becoming increasingly elusive.

As the senior J&K bank officer says, “Resolution is a theoretical issue. Since 1949, several commissions and working groups have come up with their formulations. None varied too much in content and yet each was rejected by one group or the other. The government of India in any case ignored each of them. If only we could have worked hard towards arriving at some consensus then, with some amount of give and take, perhaps the issue would have been resolved. But today, the situation is very complex with so many different factors at work, both inside and outside Kashmir. How can we resolve Kashmir now? Take for instance, the interlocutors’ report. What is so objectionable in that? Can’t that be a starting point for talks? But as a matter of habit everyone has trashed it.”

Another Window

It’s difficult to find another issue in India which is marked by so many missed opportunities and ‘almost there’ moments. Unless all those ‘almost there’ moments were a mere chimera, an extensive charade played out to buy more peace time and distract from the core issues.

But working on the premise that indeed several opportunities were missed in the past, another one is now in the offing. Despite the Indian Army’s assertions that ‘a swallow does not a summer make’, the fact is that the last six years have not been an assortment of peaceful seasons interspersed with violent times, but a gradual progression towards what can be called, for want of a better word ‘normalcy.’

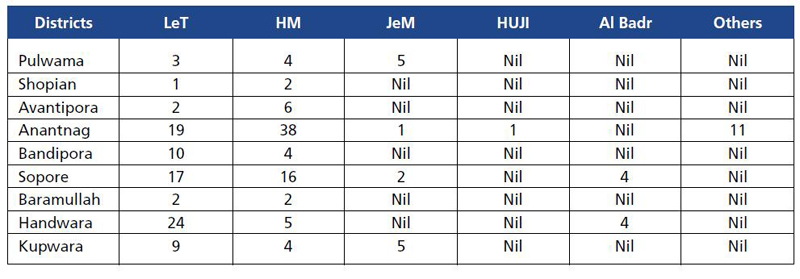

Not only is Pakistan occupied elsewhere, in terms of spawning terrorism also, with its ability to hit the mainland now, it will not like to fan trouble in Kashmir, especially when popular disenchantment with Pakistan is highest in Kashmir at the moment. Having suffered enormous losses, average Kashmiris have lost the appetite for violence; they aspire for a peaceful and prosperous future for their children. Making this claim, a senior police officer says that, despite persistent efforts, groups like the Lashkar-e-Taiyyaba (LeT) and Hizbul Mujahideen (HM) are not able to recruit cadre even in traditional hotbeds like Sopore. “There is disillusionment with Pakistan at the ground level,” he says. According to Indian intelligence sources, there are not more than 200 militants in the Valley with only 15 hardcore terrorists. A CRPF officer told FORCE that in 2011 only two people from the Valley crossed over to Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (POK) for training.

After two reasonably fair elections, there is greater faith in the constitutional institutions like the election commission, judiciary and so on. What could be greater evidence of this than the fact that Lone has jumped onto the electoral bandwagon and is urging his fellow travellers to join him. And finally, as Bhat says referring to his assertion that UN resolutions have no meaning any longer, “I don’t believe in sowing a seed during chilla kalan (severe Kashmiri winter in which nothing grows). I sow when I think it will sprout.”

While it is easy to dismiss Bhat’s statements as publicity-seeking, it would be churlish to do so. Whatever be his motives or whatever his support base be, he is planting an idea whose time probably has come. Warming up to his theme, Bhat says that as federalism gets strengthened in India, the same can be extended to Kashmir. “After all, both the National Conference (NC) and the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) are local political outfits, they are not the same as the Congress which is governed from outside,” he says. He is seconded by Lone who says, “In the last few years, political interference from Delhi has substantially reduced.” Perhaps, Lone’s People’s Conference will add political vibrancy to the state, offering a change that people yearn for.

But for the fickle Kashmiri mind, soaked in the blood of victim-hood, change has to be deep-rooted and sustained. A senior police official says that the biggest symbol of the Centre’s control on the state is the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA). “It shows that neither the J&K government nor the police are empowered,” he says. “AFSPA was promulgated for a purpose but over the years, it has been used by the army to shield malafide actions and criminals,” he adds. Clearly, it has not done any good to the army’s image either. No amount of Operation Sadbhavana or Winning the Hearts and Mind (WHAM) can wipe out the past which was ruled by such dictum as ‘get ’em by the their balls, hearts and minds can follow’. Chief minister Omar Abdullah’s suggestion that we need something like a truth and reconciliation commission in Kashmir to heal the wounds and make a fresh beginning is not without merit. If there is one issue that unites Kashmiris across political fault lines, it is the AFSPA (local Congress leaders notwithstanding). The process of reconciliation has to start with its revocation.

Enough of Talking

In the last eight years, the government of India and its various representatives have held several rounds of talks with various people in the state, from politicians to truck drivers. Thousands of pages of documents have been compiled on who wants what and what the government should do. Several roadmaps for peace have been prepared. Yet, all of them lay gathering dust in Delhi.

The most recent such document is the over 100-page report of the three interlocutors appointed by the government of India. The report which was submitted to the ministry of home affairs was recently uploaded on the ministry’s website. But the government is yet to table it in Parliament. Perhaps it is seeking wider opinion on it by putting it in the public domain – which is not such a bad thing. Charting the middle path, the report draws extensively from all past documents, including the recommendations of the working groups created by the government following the second round table conference with Kashmiri leaders in May 2006.

Even if the report is not accepted in its entirety, it can form the basis of steps towards reconciliation and resolution. Clearly, the report is not the answer to everything that ails Kashmir (including the issue of the Kashmiri Pandits’ right of return), but it can be the starting point so that another window of opportunity does not close. After heeding intelligence inputs for the last two decades and making those the basis of policy-making, the government of India needs to heed imaginative, magnanimous ideas, before it’s too late.

As the banker repeatedly insists, the situation in the state is getting increasingly complex with religious radicalisation introducing a completely new dynamic. Bashir says, “The lack of dignity and hope are breeding grounds for radicalism whether it is of a religious or political kind.” Not only are stray voices against the Shias and Ahmadis being raised, within the Sunni community itself, as in Pakistan, radical groups of Deobandis and Barelvis have come up. “There is no mosque left in Kashmir for a Muslim,” laments the banker. “Each mosque has a name of the group it belongs to.”

Many in Kashmir even today dismiss radicalisation as more of a bogey raised by paranoid people. They forget that radicalisation is not a revolution; it creeps almost unnoticed till such time that it overtakes you. To justify radicalisation on the grounds that Kashmir has always been a conservative society is making excuses. Conservatism is not radicalisation; the former is personal, the latter is public and consequently intolerant.

Given the geography and history of Kashmir and its eclectic mix of ethnicities, the combination of terrorist violence and religious radicalisation would be disastrous. “Each home in Kashmir is an institution where history is taught,” Bhat told FORCE. It is time we change the narrative.

There are a few more which move from district to district, taking the grand total to about 200, according in Indian intelligence sources.