India’s China strategy needs a serious rethink

Capt. Jawahar Bhagwat PhD (retd)

Capt. Jawahar Bhagwat PhD (retd)

In its April 2020 report, titled ‘Global Military Expenditure Sees Largest Annual Increase’, Stockholm-based think-tank Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) wrote, ‘In 2019 China and India were, respectively, the second- and third-largest military spenders in the world. China’s military expenditure reached USD261 billion in 2019, a 5.1 per cent increase compared with 2018, while India’s grew by 6.8 per cent to USD71.1 billion.’ Quoting its senior researcher Siemon T. Wezeman, the report added that, ‘India’s tensions and rivalry with both Pakistan and China are among the major drivers for its increased military spending.’

PLA Navy (PLAN) has been sending ships and submarines to operate in the Indian Ocean for some years now. It is not the only foreign navy operating in the Indian Ocean. The government of India and the navy have been making public statements regarding Indian Navy monitoring the activities of the Chinese Navy in the Indian Ocean.

India hopes that China’s dependence on the Malacca Straits for passage of oil and other strategic minerals could be exploited during a conflict. India has also gone along with the United States (US) in being a party to an artificial ‘Indo-Pacific’ construct. China has resolved land border disputes with all countries other than India, including Russia and Vietnam with whom it had border skirmishes much later than that with India. However, it continues to hold onto mainly maritime claims regarding Taiwan, the South China Sea and the Senkaku-Diaoyu islands held by Japan.

Historical Perspective

The ‘China Factor’ in Indian foreign policy has been an important issue for Indian politicians. In the Fifties, the fraternal friendship between the two countries led by strong leaders, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Chairman Mao Zedong promised to redefine Asia. Dreamers even entertained the idea of India and China piloting a post-colonial renaissance in the developing world.

However, this idealistic vision was short-lived and ties between China and India have been under great stress since the 1962 war. Though Chinese troops withdrew from Indian territory after approximately a month subsequent to achieving its political and military goals, the relationship between the two giant Asian neighbours has been based on mutual distrust, rivalry and occasional border clashes and skirmishes. This trust deficit is exacerbated by China’s longstanding relationship with Pakistan, India’s defeat in the 1962 Sino-Indian war, border disputes and increasing competition for resources and influence.

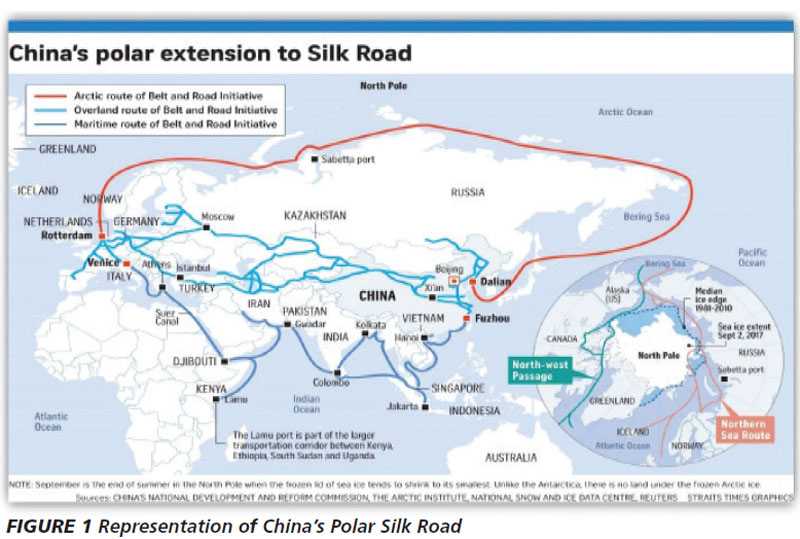

Interestingly, most Indian politicians and members of the security establishment are unaware that China’s one century of humiliation commenced with the Opium wars in which Indian soldiers recruited by the East India Company played the key role in an attack on Hong Kong, the sacking of the Forbidden City and the aftermath. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has further complicated the relationship between Asia’s two fastest growing powers. The ongoing border dispute, trade imbalances, and competition for influence across South and Southeast Asia also thwart efforts to reduce the pervasive mistrust. Ultimately, this mistrust challenges the security and stability of the entire region. As of today, the border dispute between India and China still remains unresolved. Large border areas to the east and west of Nepal and Bhutan are under substantial military surveillance by both countries.

This ‘China factor’ continues to linger in Indian foreign policy issues. Though steps have been taken by both India and China to normalise relations, a deep sense of mistrust remain. Many commentators have termed the 21st century the ‘Asian Century’, a period where India and China are expected to rise to become global great powers as in the past. Consequently, the relationship between these two countries will have wide-ranging consequences for the rest of the world. New Delhi and Beijing do find common ground and cooperate in international forums such as the BRICS, the G20 and Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), in addition to climate change conferences.

The strategic alliance between China and Russia has the potential of becoming the so-called ‘strategic triangle’ between India, China and Russia. The former Russian Prime Minister Yevgeny Primakov was the architect of this idea. Although this triangle has been inconsequential in terms of deeper cooperation between the three countries, it is still perceived in the international political discourse as a ‘power balancer’ vis-a-vis the United States in advancing a multipolar world order. The larger geopolitical picture depends on how the Sino-Russian relationship converges or diverges.

PLA Navy Force Level and Capability

In terms of force levels there is no comparison between India and China. The last two decades have seen an exponential growth in Chinese military spending coinciding with consistently high economic growth. The PLA Navy has particularly been a beneficiary of this increased military spending.

A recent US Congressional report, ‘China Naval Modernisation: Implications for US Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress’, written by Ronald O’ Rourke pointed out that, ‘China’s navy, which China has been steadily modernising for more than 25 years, since the early to mid-Nineties, has become a formidable military force within China’s near-seas region, and it is conducting a growing number of operations in more distant waters, including the broader waters of the Western Pacific, the Indian Ocean, and waters around Europe. China’s navy is viewed as posing a major challenge to the US Navy’s ability to achieve and maintain wartime control of blue-water ocean areas in the Western Pacific—the first such challenge the US Navy has faced since the end of the Cold War—and forms a key element of a Chinese challenge to the longstanding status of the US as the leading military power in the Western Pacific. China’s naval modernisation effort encompasses a wide array of platform and weapon acquisition programmes, including anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs), anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs), submarines, surface ships, aircraft, unmanned vehicles (UVs), and supporting C4ISR (command and control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) systems. China’s naval modernisation effort also includes improvements in maintenance and logistics, doctrine, personnel quality, education and training, and exercises’.

An article by Michael Evans (The Times, 16 May 2020) states, ‘The United States would be defeated in a sea war with China and would struggle to stop an invasion of Taiwan, based upon a series of ‘eye-opening’ war games by the Pentagon. American defence sources informed the newspaper that simulated conflicts conducted by the US concluded that their forces would be overwhelmed’.

You must be logged in to view this content.