How Indian Army exemplified the best military traditions in its engagement with Pakistani PoW after the 1971 war

Ravi Palsokar

Ravi Palsokar

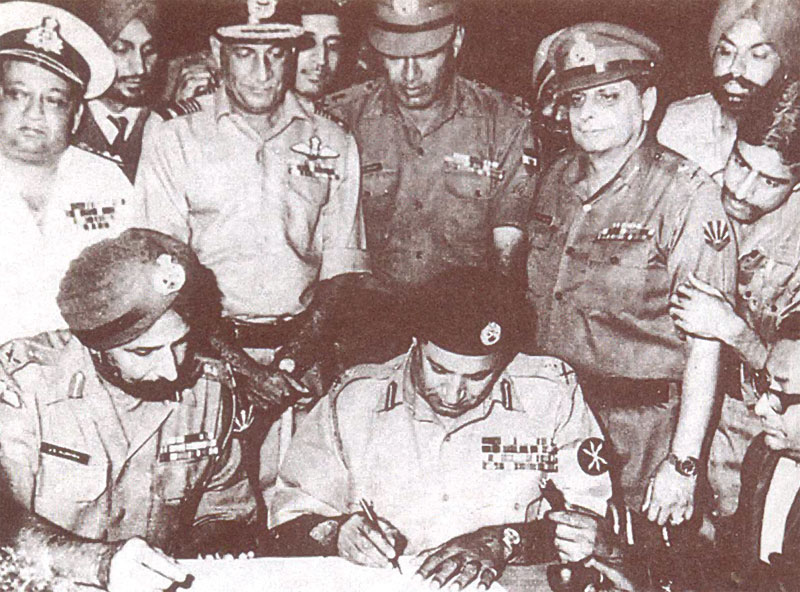

This year India is celebrating the Golden Jubilee of her victory over Pakistan in December 1971. The war ended with the creation of Bangladesh and one of its after-effects was that the entire Pakistan Army in the east had surrendered. India then had to house, feed and generally administer some 93,000 prisoners of war (PoW) among whom were a few families of officers and soldiers. These PoW were repatriated after the Simla Agreement between India and Pakistan. However, this took time and the PoW were handed back in late 1973 and early 1974. Till then it was our task to look after them according to the Geneva Conventions. Right from the beginning, the country’s leadership had decided that the PoW would be treated humanely and this was followed in letter and spirit.

The task of lodging and administering the PoW was given to Headquarters Central Command which established the required numbers of camps in the various stations under their Command. The PoW were housed in barracks vacated by our troops, who in 1972 were still deployed at the border. It was fortuitous that the C-in-C of Central Command was Lt. Gen. P.S. Bhagat, VC, who it was soon proved was the ideal man for the task. He laid down very strict rules and procedures to ensure that the PoW were treated with empathy and due firmness without compromising security. The efficacy of this policy soon became apparent when Pakistan started worrying about India’s influence on their soldiers.

As can well be imagined, the actual work of managing and administering the PoW camps fell to junior officers under the watchful gaze of our superior headquarters right up to Command HQ. Personally, I was between postings when the war ended and was shifted to command one such camp in Gwalior. I had not completed 10 years of service and the three officers under me had even less. We were young and ignorant and started our work using first principles of administration of soldiers. This was as good a method as any and we were able to rise to the expectations of our wise Army Commander.

This is the story of that period when I was a PoW Camp Commandant for a period of little over one year. In this set-up we began work and initially there were many glitches. One example was the preparation of a muster roll of PoW showing who exactly was in the Camp. Army number, rank, regiment, age, was easy. The problem was that every other Pakistani soldier had `Mohammed’ in his name and they all spelled it differently. As we were being defeated by this seemingly innocuous difficulty, we agreed that forget the full form, the name would always be abbreviated as Mohd. This simplified the process and we improvised like this all the time.

Routine and Activities

The routine was the same as what we followed in our army. Fortunately, as the Pakistan Army had similar procedures, it was easy to get the PoW to conform and they too recognised what they had to do. There was one major difference in that there was a roll call three times a day, so that any escape could be noticed within the space of few hours. After dinner, the PoW were confined to their barracks except to answer the call of nature and arrangements were made so that these facilities were used only at night. The bathrooms and latrines were in one corner and had waterborne sanitation.

The Camp staff had no responsibility for external security. This was provided by a unit sized force usually of the Territorial Army or the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF). They had their own rules and procedures for guard duties, their turnover, administration and everything that a unit does. Every camp had three fences, the first enclosing the barracks, the second a few metres away and an outer perimeter. The space in between could be patrolled by the sentries and outside the outer fence there were watch towers and for the night, flood lights. Additionally, inside the camp nearest the first wire fence, a line was drawn one metre inside, beyond which a PoW could not approach the fence on the pain of being shot at. This was a wise precaution.

How had such detailed instructions been put in place so quickly? No one told us but I surmised that some obscure office in Army HQ had dusted out old instructions which in turn were passed on to us. It was efficiently done under the supervision of the Army Commander who had a wholesome, if intimidating, reputation as an able administrator. Soon after the Camp had been set up and we were settling in, Gen. Bhagat decided to visit each and every camp, see the arrangements and address the PoW. In my Camp, a makeshift PA (public address) system was rigged up and the PoW stood in formation outside their barracks to listen to the General. He assured them that they would be treated as soldiers and with the dignity that they deserved. As he finished, the entire Camp broke into a spontaneous applause by clapping vigorously. Even Gen. Bhagat was pleasantly taken aback by this response and he showed his appreciation to the assembled by waving to them with a big smile. This led to even more clapping. So, we began on a right note. It occurred to me later that the incident reflected positively on both, the obvious authority and charisma of the General as well as the discipline of the PoW.

Within the first few days a routine was laid down for the PoW which approximated with what we were all used to, that is Reveille in the morning, a PT period before breakfast, some activity till lunch and again in the evening, till dinner after which there was Lights Out. It sounds innocuous but one could not avoid the tension the PoW worked under. Once again, my officers and I fell back on what was familiar to us all by organising activities which would keep them busy within the limited confines of the Camp. In our case, I set aside a major part of the morning in keeping the Camp and the cookhouses clean. There was no place within the Camp that was not cleaned and smoothened with water, every brick was coloured as one sees within military areas and this was done under the supervision of their NCOs. Similarly, one of the PoW NCOs came up with the idea that each barrack should provide a drill squad and a lot of time was spent parading them, eventually leading to an inter-barracks competition. It must be admitted that they were just like our men and impressive in their bearing and smartness. A chance compliment only served to motivate them and often they would take pride in demonstrating the smartness of their squads.

You must be logged in to view this content.