From conundrum to crossroads, how Kashmir continues to exercise hearts and minds

Ghazala Wahab

Ghazala Wahab

During his tenure as the chief of the army staff (2003-2005), Gen. N.C. Vij gave no interviews. Either he did not trust any journalist, or he did not trust himself. Whatever may have been the reasons for his reticence, the silence maintained the illusion of depth and gravitas. What a pity then that just when there was no need to do so, he decided to distrust his own instincts and give in to the persuasions of his sycophants.

The consequence of this moment of weakness is his first book—The Kashmir Conundrum: The Quest for Peace in a Troubled Land—, which he was better off not writing. I am saying this for at least five reasons. To begin with, by Gen. Vij’s own reckoning, The Kashmir Conundrum was not the book he intended to write. He says he wanted to write a book or two to share my experiences—relating to my profession of arms and the nuances in planning and decision-making in the higher echelons of the army and the government in the areas of national security and nation building.

Since none of that came to pass, ‘some friends suggested that I write a book about Jammu and Kashmir.’ While the former could have been instructive for the coming generations of military officers, the latter serves only one purpose—adding decibels to the government propaganda.

Gen. Vij allowed himself to be persuaded as he felt that being a Dogra from the Jammu region of the state, he had an insider’s view; and having served in the state as a senior level military officer, he had the bird’s eye view as well. Hence, harnessing memory and experience, Gen. Vij presents, in his début book, his prescription for the resolution of the Kashmir conundrum. Incidentally, one of his earliest memories of the state was ‘witnessing, even as a ten year old, the spontaneous agitation that broke out in Jammu after the death of Syama Prasad Mukherjee, founder of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh on 23 June 1953 in the state prison.’

While childhood memories are benign, recounting them after 68 years cannot be without a purpose. And Gen. Vij’s objective is spread across the 400-odd pages of his book. But before I get to the reasons why this book should not have been written, an observation first.

Language has been important, both for the government of India and Kashmiris, to describe the violence in the state. For a long period of time, both used the term insurgency and militancy. Sometime in the last decade, government replaced the word ‘militant’ with ‘terrorist’. Thereafter all official communications, including press releases, referred to Kashmiri insurgents as terrorists. However, Kashmir-based journalists continued to use the term ‘militant.’ Being a defence magazine, FORCE used to change that to ‘terrorist’ in the copies we received from Srinagar, because that had become the Indian Army lexicon—counter insurgency/ counter terrorism operations (CI/ CT ops). Our Kashmir correspondent requested us not to make this change, ‘at least in my copy’. This was a sensitive issue for them. Thereafter we reverted to ‘militant’ unless there was a direct quote from an army/ government official. However, both the government and the mainline media continue to refer to Kashmiri insurgents as terrorists.

Gen. Vij uses the phrase ‘counter insurgency and counter-militancy’ to describe army operations in J&K. While he refers to unknown insurgents as terrorists, including the hijackers of IC-814, Burhan Wani and Zakir Musa are called militants. It’s not clear if he is consciously making this distinction or carelessly using the two words interchangeably. I would like to believe the former, because a former COAS, founding vice-chairman of National Disaster Management Authority and former director of Vivekanand International Foundation, cannot run fast and loose with language. Why he is doing this, is a mystery though.

Now, to come to why this book should not have been written.

One, the centre of gravity of any political problem are the people. Nobody, not even Gen. Vij, doubts that Kashmir is a political problem; he devotes a chapter, albeit the smallest one, to various formulas put forward to resolve the Kashmir issue, starting with the 1950 UN partition plan. The chapter ends with Prime Minister Manmohan Singh-President Musharraf’s back-channel process. What’s more, he has got Dr Karan Singh to write the Foreword, in which Singh says, ‘…the relationship of Jammu and Kashmir was based on Articles 370 and 35A of the Constitution…’

Yet, the Kashmiri, as a voice with perspective, is missing from Vij’s narrative. Devoting half the book to lauding the revocation of the aforementioned articles on 5 August 2019, Gen. Vij is mindful of the sentiments of the people of UP and Rajasthan—who are happy that Kashmiris are as much a part of India as they are–, but dismisses Kashmiris as those remaining ‘unhappy with the change, that too primarily because of being under the influence of Pakistan and radicalisation.’ Two paragraphs later, he writes, ‘The people of Kashmir, who are central to the problem, remain alienated, angry and frustrated. However, this is likely true of 30-40 per cent of the population. The rest are probably either fence-sitters or perhaps are satisfied…’ Likely? Probably?

Two, if dismissal of Kashmiri voices was not bad enough, Gen. Vij also robs them of their grievances. The decades since 1989, the deaths, the unmarked mass graves, the half-widows, the disappeared people, the torture chambers, and the memories, all of this is clubbed together as radicalisation. And by Gen. Vij’s reckoning, radicalisation is ‘probably’ a chemical process, which can ‘likely’ be reversed through another process. This process will involve enlisting the support of ‘important seminaries such as the Darul Uloom Deoband’, never mind that for the longest time the government of India blamed Deoband for radicalisation in Kashmir and airdropped the Barelwi sect to counter the Deobandi effect. Also, please ignore that the emergence of Taliban was blamed on the Deobandis. These days, they are the good guys.

But this is not enough, the deradicalisation ‘strategy will also have to include efforts to revive Kashmiriyat and Sufism…’ Sadly, none among the fellow army officers that Gen. Vij consulted and have acknowledged, told him that Deobandis disapprove of Sufism and Sufi shrines. Anyway, not to nit-pick, quoting Lt Gen. Ata Hasnain, Vij writes that, ‘The deradicalization strategy will be a battle of hearts and minds. Hasnain suggests that first of all, research must be carried out to identify how to counter the causes of radical belief. India needs to look at successful models of countries such as Malaysia…’ Wow!

Three, Gen. Vij refers to Article 370 as a ‘transient provision…, and had to go.’ Here he not only disagrees with the person who wrote his Foreword, he is also misinterpreting both the Instrument of Accession and the Indian Constitution. He also ignores the fact that Kashmir is an international dispute, listed with the United Nations and today has four stakeholders—Kashmiris, India, Pakistan and China.

Clearly, his brief was to write how great the revocation of Articles 370 and 35A have been for India’s global stature and its national security. Tasked with the impossible he had no choice but to paper over the bitter truths. Hence, while, ‘The Howdy Modi event in Houston in September 2019 was a grand spectacle and raised the stock of Indians the world over,’ ‘…the union territory of Jammu and Kashmir has to be elevated to the status of one of the most progressive states in the country.’

The problem however is, ‘the Kashmiris have been used to looking at life through a narrow and self-centred prism and have never given a second thought to their other state mates, the Jammuites and Ladakhis. That will now not work,’ he warns.

Four, and this is the most shocking part of the book. No amount of prejudice or sycophancy can justify the level of ignorance of geopolitics that Gen. Vij displays. He has not only been the army chief, he was also director general military operations during Operation Parakaram and had the ring side view of what an unmitigated disaster it was, that despite the amassed Indian Army on the border, Pakistan did not blink. It actually called off India’s bluff, forcing the Vajpayee government to end the military mobilisation mumbling military coercion. Thereafter, Gen. Vij was director VIF, one of India’s most effective think-tanks, founded by the present national security advisor, and patronised by the ruling party. In the last decade, VIF has attracted the best of global thinkers, researchers and scholars.

And yet Gen. Vij is not embarrassed writing that India must wrest Gilgit-Baltistan from Pakistan. He proposes a two-prong strategy: ‘The muscular approach could be one important option out of several others. These other options could include encouraging and supporting the ongoing freedom movement in these areas.’ Once Gilgit-Baltistan is incorporated into Jammu and Kashmir, ‘Pakistan and China will have no contiguous border.’

‘This action will pitch India face-to-face with the Chinese in the CPEC area… This may be worrying the Chinese, and hence their pronouncements on Kashmir are becoming shriller.’

Old India proverb kept playing in my mind as I read through Kashmir Conundrum—Bandh ho mutthi toh lakh ki/ Khul gayi toh khaak ki (a clenched fist holds a lot of promise/ but once open it exposes its emptiness). Gen. Vij was sensible when he was the army chief.

Oh, and the fifth reason, Sumantra Bose’s Kashmir at the Crossroads: Inside a 21st-Century Conflict, which came a week before Gen. Vij’s book. The timing couldn’t have been worse. Bose is an old hand on Kashmir, not because he first went there as a tourist in 1976, but because he stayed in touch with the subject, through available literature, historical documents and, most importantly, Kashmiri voices. His book is informed with these voices—from the streets, local police stations, lower courts, media houses and drawing rooms. No wonder then that the book is both sensitively and sensibly written.

Since Bose had produced a comprehensive work on Kashmir in 2003 called Kashmir: Roots of Conflict, Paths to Peace, which suggested the way forward to lasting peace in the state, a somewhat similar proposition to what eventually formed the basis of Manmohan-Musharraf back-channel dialogue, Kashmir at the Crossroads frequently references that. The new argument in the book follows the revocation of Articles 370 and 35A and the diminution of the state into two union territories.

Contrary to Vij’s assertion, Bose writes: ‘…the actual cause of “separatism” in the state…, was the de facto revocation of its autonomy in the 1950s and 1960s and the manner it was effected: through the collusion of puppet state governments installed by New Delhi and by turning the territory into a police-state ruled by draconian laws.’

Bose points out the irony that while the Hindu nationalist groups have been protesting the existence of Article 35A in Kashmir, ‘at least half a dozen other Indian states have very similar protection for native residents.’ He does not hold back when writing about Modi government’s vision for ‘naya’ Kashmir: ‘It entails making loyal Indians out of disloyal Kashmiris through a mixture of strict discipline and what is known in… China as “re-education”.’ Thereafter, he proceeds to call today’s Kashmir ‘A hell on earth.’

Unlike Vij, who is sanguine in the belief that the Kashmir issue has been resolved by the Modi government, Bose’ conclusion is dire. With China now an active party to what was historically a bilateral dispute between India and Pakistan, Kashmir today is ‘rife with incendiary ingredients’ with can lead to a devastating regional conflict. The only saving grace is that this conflagration may eventually resolve the Kashmir issue. No sensible person can argue with this assessment. May Bose’ book be widely read.

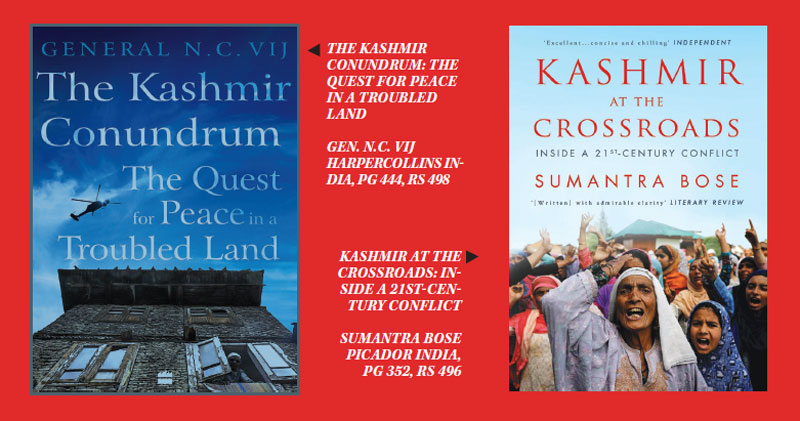

THE KASHMIR CONUNDRUM: THE QUEST FOR PEACE IN A TROUBLED LAND

Gen. N.C. Vij

HarperCollins India, Pg 444, Rs 498

KASHMIR AT THE CROSSROADS: INSIDE A 21ST-CENTURY CONFLICT

Sumantra Bose

Picador India, Pg 352, Rs 496