Myanmar is strategically important and India should get a strong foothold in the country

Smruti D

On the world map, Myanmar sits at a geographically strategic position. It shares borders with both India and China; and as the world stares at the power tussle between India and China, the Asian context of Myanmar increases manifold.

The Southeast Asian country shares 1,643 km of border with four Northeast Indian states that include Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur and Mizoram. The two countries also share a maritime border of about 725 km. Apart from India, Myanmar shares border with Bangladesh, China, Thailand and Laos. Myanmar is famously known as India’s ‘gateway’ to Southeast Asia, and is among the countries flanking the Bay of Bengal. As China bids to increase its influence globally to realise the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), investing in growing Asian economies helps realise its objectives. Myanmar is one such country with its distinct geographic location.

The Bay of Bengal

It stretches more than 2,173,000 sqkm and lies in the north-eastern part of the Indian Ocean. It is of importance for several littoral and landlocked countries for trade and transit. The Bay of Bengal, beginning from the southwest and taking a long curve to reach the southeast (to end there), holds together the coastlines of Sri Lanka, India, Bangladesh (the head of the Bay), Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia’s Sumatra. Apart from these states, landlocked countries in the vicinity of the Bay—Nepal and Bhutan—are dependant on it. Consequently, its strategic and economic potential cannot be overemphasised.

Historically, the Bay served as a maritime highway for countries surrounding it, resulting in exchange of trade and cultural ties. As centuries progressed and European powers began staking control of different Asian countries along the Bay, and although a change in geostrategic relations took place, the importance of the Bay of Bengal remained intact. Later, when agricultural production began booming in these countries, a migration, that later came to be recorded as one of the largest in the history, took place via the Bay of Bengal.

Over a period of time, with the advent of steam ships, the Bay of Bengal played a vital role in connecting countries with one another. As time went by, countries around the Bay, including India, adopted a largely internal stance. Gradually, the economic interdependence and free trade was put to an end. The defocus was further strengthened when the countries in the region came to be divided into two parts—South Asia and Southeast Asia. While the northern and western countries of the Bay were regrouped in South Asia, the eastern part came to be called Southeast Asia.

The Bay regained importance gradually. The aforementioned countries surrounding the Bay have a GDP around USD 2.7 trillion and an economic growth of around 5.5 per cent, according to a report published by Carnegie India. “With the economic reforms of the Nineties in India and across South Asia, however, the Bay of Bengal’s geo-economic centrality and legacy of integration was slowly reactivated. Driven by the new logic of interdependence and comparative advantage, states in the region began seeing borders as connectors and invest in the infrastructure of connectivity to permit greater flows of goods, services, capital and ideas. No longer a gulf of disintegration, the Bay of Bengal slowly began assuming the role of a hub to leverage synergies between South and Southeast Asia,” the report states.

China’s strategy in the region lies in connecting the landlocked southern provinces with the Indian Ocean. The Bay stands out as a key transit zone between Indian and Pacific oceans along with being the main route for energy trade to east Asia. With the central position of the Bay, other major world powers like Japan, the US and Russia, too, are trying to assert their power in the region.

BIMSTEC

In 1997, Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), a seven-member regional intergovernmental group was formed. For India, an active participation in this grouping would help protect its regional influence and interest in the Indian Ocean.

BISMTEC has a large economic and development potential. Home to 23 per cent of world’s population, the grouping brings together economies that amount to USD3 trillion which translates into four per cent of global GDP and 3.7 per cent of the global trade. This grouping has an enormous trade potential of USD760 billion. However, in 2017 the intra-regional trade stood at USD83.90 billion.

BIMSTEC is a group that unites five South Asian countries including India, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal and Sri Lanka with two Southeast Asian countries, Myanmar and Thailand. Myanmar has a greater role to play as it shares a land border with India and lies between India and the southeast. Experts believe that the fact that India has increased its cooperation with the BIMSTEC states is because it is wary of China’s increasing presence in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). Many have termed this as ‘reactionary regionalism’ that arose out of the growing concern of Chinese influence. It is of great significance that in the BIMSTEC grouping, all countries, except India and Bhutan are signatories to the BRI, with huge Chinese investments. From the Indian perspective, the grouping gives a way to Myanmar to tilt towards South Asia and balance its cooperation between China and South Asia. As the disputes between India and Pakistan increased, India shifted its focus from SAARC to BIMSTEC. The latter does not include Pakistan. Under the grouping, India has signed several development projects with Myanmar for greater scope for trade and connectivity. The intra-regional trade among these countries is still low due to the lack of implementation of the Free Trade Agreement.

On why Myanmar holds an important place for China, Manoj Joshi, a distinguished fellow at the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) says, “BIMSTEC is Bay of Bengal body, Myanmar is geographically an important part of the body. Myanmar has equidistant relations with both. It has good economic ties with China and also good political ties with India. India shares a land and maritime border with Myanmar and it can become an important means of connecting to other ASEAN countries.”

ASEAN

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is another important grouping that is important for India, even though it is not a part of it. It consists of 10 members including, Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.

ASEAN plays an important role and is the steering wheel for India’s Act East policy. Although India is not a member, in 1992, it became a dialogue partner and achieved the full dialogue partnership in 1995. A year later, ASEAN gave India the opportunity of appearing in the Post Ministerial Conference (PMC) and secured a full membership of the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF). The IOR is plagued with piracy, illegal migration, human, drugs and arms trafficking along with a rising threat from maritime terrorism. This platform enables discussions around these issues that demand attention on a multilateral level. ASEAN PMC and ASEAN Defense Ministerial Meetings-Plus (ADMM-Plus) are also significant platforms for India to discuss security. India has signed Joint Declaration for Cooperation to Combat International Terrorism with ASEAN to combat terrorism collectively.

ASEAN countries have always had to balance their way in between growing regional powers. India’s trade with ASEAN as of 2018, stands at USD81.33 billion, which amounts to 10.6 per cent of India’s overall trade. India’s exports to the region amount to 11.28 per cent of its total exports.

As both these groupings deal with Southeast Asian countries for boosting trade and security, it is important for India to have a strong stepping stone in the region, which is Myanmar. Politically, economically and infrastructurally stable Myanmar would only add to India’s interests in the region and ward off the growth of an unwarranted Chinese influence in the country and subsequently in the region.

Importance of Myanmar

Myanmar is significant to India as a connecting point with other southeast Asian countries, thus making it crucial for India’s ‘Look East’ policy that is now called ‘Act East’ policy. As India’s northeastern states are plagued with insurgencies, Myanmar, as a neighbour, has a key role to play.

The fact that the Strait of Malacca opens in the Bay of Bengal underlines the importance of the region for India, especially that of Myanmar. It connects the Indian Ocean with the Pacific Ocean. It is also the shortest waterway that links the Indian Ocean with South China sea.

The Malacca strait is the busiest commercial crossing in the world with almost 60 per cent of the maritime trade transits taking place via this strait. It lies between Malaysia and Indonesia which enables majority of Chinese imports. China’s huge oil imports (80 per cent in 2016) and 11 per cent natural gas imports from Venezuela, Angola and Persian Gulf passes through this route. India has natural ports in the form of Andaman and Nicobar island and holds the capability of building a significant military presence, near the strait, which China perceives as a threat. In case tensions rise any further, China is aware that the ships can be stopped and taken control of by the presence of the leading power in the Indian Ocean. Indian Navy’s ‘Mission Based Deployment’ ensures spotting of Chinese ships in the Indian Ocean with 50 of its ships already deployed in the IOR. To reduce its dependence over the strait, China has been seeking other options in connectivity which includes Myanmar. Myanmar is also rich in natural resources.

Suyash Desai, China Studies Programme, The Takshashila Institution, says, “Myanmar occupies a vital role in China’s Grand Strategy conception under Chairman Xi Jinping. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) under China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC)—aims to connect the Indian Ocean oil trade to China’s Yunnan Province. This gives them another opening in the IOR besides Pakistan and allows them to circumvent the South China Sea and the Malacca Strait, which during escalation could be vulnerable. It has managed to achieve this by knitting together a series of strategic ports, railways and pipeline projects across Myanmar providing better access to the sea. Myanmar is also a resource-rich state with an abundance of tropical timber, rich rice lands, oil and gas, and precious gems (sapphires, rubies, jade). Thus it acts as an essential trade destination and investment asset for the PRC.”

He adds that it has a relatively large and prosperous ethnic Chinese population in the country because of two centuries of migration. Finally, it also could be used by China to keep India in check by keeping separatist shenanigans alive in India’s Northeast.

India and Myanmar

India and Myanmar share ties in terms of trade, investments, defence and most importantly security. In February 2019, the Tatmadaw, which is the Myanmar Army, conducted counter-insurgency ops against Indian insurgent groups, destroying camps, seizing arms and ammunition and arresting insurgents belonging to the National Socialist Council of Nagaland-Khaplang (NSCN-K) and Meitei insurgent groups.

Crossing over to Myanmar, the insurgents take shelter, plan their offensives and launch attacks in India. A data by security forces suggested that as compared to 2019, insurgencies have come down in 2020. Anti-insurgency ops in Northeast led to 2,259 surrenders this year. A total of 261 arrests have been made. However, a large number, more than 40, as per the New Indian Express report, continue to exist in Myanmar. The Indian and Myanmar army carried out Operation Sunrise against Indian insurgent groups in three phases between January and May 2019 and March 2020.

Apart from insurgencies, there is also a rampant smuggling of arms and ammunitions and drug trafficking. Insurgents tend to exploit various factors like the Free Movement Regime (FMR) that permits tribes from each of these countries to cross over to the other border visa-free up to 16 kms. Other factors include the dense India-Myanmar border terrain which makes policing difficult. Even though in 1967 a border was demarcated, the ethnic groups living on either sides continue to support each other’s causes and let persons of the same ethnicity take shelter in their homes. Hence, even though a border is in place, the locals refuse to accept it.

Due to these regions and adverse security breach that they cause, the relation between India and Myanmar had strained. Rajeev Bhattacharya, a senior journalist covering insurgencies, says, “Insurgency had strained the ties between India and Myanmar in the past. Myanmar government’s inability to prevent Northeast rebel outfits from establishing camps and training facilities in its territory prompted Indian intelligence agencies and army to make their own efforts at checking them. This resulted in R&AW’s pact with Kachin Independence Army in the late-Eighties. Then, Yangon was upset and this was further compounded by the grant of an award to Aung Sang Suu Kyi in 1995. Predictably, Tatmadaw refused to cooperate with the Indian Army during Operation Golden Bird in 1995. Subsequently, although the ties improved, there was no action against the rebel groups for a long time barring certain exceptions. It was only in the last one-and-a-half years that some action by Tatmadaw against the outfits was visible. The rebel base at Taga in Myanmar’s Sagaing Division was dismantled and many functionaries were also handed over to India some months ago.”

Recently, Myanmar also blamed China for arming the Arakan Army, a rebel group on its territory. It is an important factor to take into account as rebel groups stall development processes. Bhattacharya adds, “It has been a long-standing policy of many countries to support rebel groups and China is no exception in this regard. Beijing’s policy underwent a major shift after Deng Xiaoping assumed power in the late Seventies. This was best manifested in the downfall of the Communist Party of Burma in 1989 which splintered into five outfits. However, China continues to maintain close ties with and sell weapons to many rebel outfits in Myanmar. The reason is Myanmar’s strategic significance and Beijing has been implementing a ‘carrot and stick’ policy in the country to maintain its grip. The BRI project in Myanmar is aimed at fulfilling many objectives of China. Myanmar has already expressed serious concern over China’s ties with some rebel groups. The United Wa State Army, for instance, which receives weapons and other assistance from China, runs a parallel government in northern Shan State. Tatmadaw could be suspecting that the same model might be repeated in Rakhine State by Arakan Army if not checked and it is currently engaged in operations against the outfit. India’s multi-crore Kaladan project has been stalled because of disturbances in Rakhine and Chin states. China also wanted an alliance involving all separatist groups in India’s Northeast but that has not worked out so far.”

Since insurgencies seriously affect the bilateral relationship and only help China further its intentions, the way forward, Bhattacharya says, is greater engagement. He even suggests an Indian presence in Myanmar. He adds that genuine efforts ought to be made to understand Tatmadaw’s compulsions. It has to keep the battle going against the rebel outfits on various fronts. Insurgencies cannot be wiped out overnight and especially when it involves outfits like the Arakan Army, which has a cadre strength of around 9000. Finally, India can certainly have a greater role in the development of the border regions which are among the most backward in both the countries.

In 1970, India signed a bilateral trade agreement with Myanmar. Bilateral trade in between the two countries has been growing steadily. India is presently the 11th largest investor in Myanmar and most investments have been in the oil and gas sector.

India has engaged in several ambitious river and land-based projects in Myanmar for connectivity. The Sittwe port in Myanmar part of the greater Kaladan Multi-Modal Transport project was initiated by India and Myanmar to connect Sittwe port (located in Rakhine state of Myanmar) to India-Myanmar border. The Tamu-Kalewa-Kalemyo road project also known as the trilateral highway connecting India-Myanmar and Thailand is a part of India’s plans to connect with Thailand via Myanmar.

In November 2019, the Indian Army handed over 10 military Tata Safari Storme SUVs to the Myanmar Army. India is one of the top five exporters to Myanmar which includes China too. India’s military to military ties with Myanmar include training, joint surveillance, maritime security, medical cooperation among other things. India-Myanmar bilateral defence cooperation, last year, included a USD37.9 million contract for supplying indigenously built torpedoes which Myanmar bought from India along with another contract of transferring a Russian-made Kilo-class diesel-electric submarine.

To maintain close ties, India handled the Rohingya crisis and the treatment meted out to them diplomatically and did not condemn the atrocities. While India saw an influx of Rohingyas, it did not go all out in criticising the Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi.

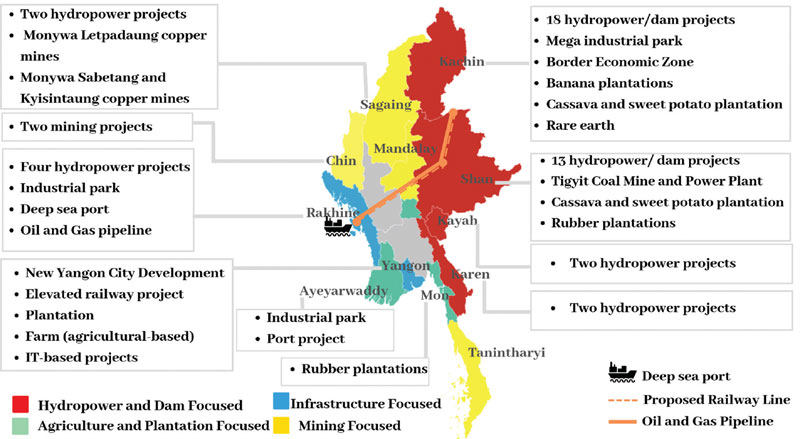

Chinese Investments in Myanmar

China has invested heavily in Myanmar and is the largest source of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in the country with 20 per cent investments, as per the Directorate of Investment and Company Administration (DICA). In comparison, Indian investments stand far behind China’s at just 3.7 per cent. China is also Myanmar’s largest trading partner.

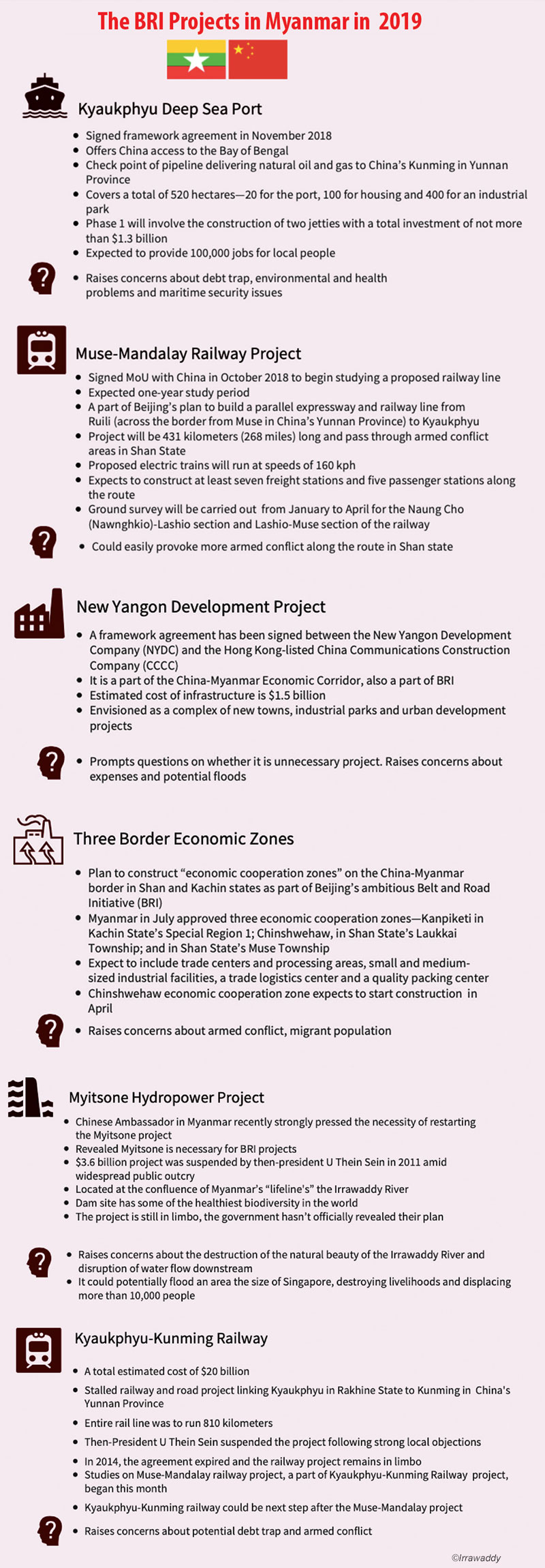

China’s investments became starkly visible in Myanmar after 2008 when Myanmar signed an agreement with China and allowed it to take up three major investments. The USD3.6 billion Myitsone Hydropower project, which was signed in 2006 was to be built by China’s State Power Investment Corporation. The construction for the project began in 2009. However, more than a decade later, the project hit a roadblock as Myanmar faced opposition from its own people living in the Kachin state, where the dam was to be built. China has been long trying to revive the project. It was first suspended by former president Thein Sein in 2011 after protests that called for a halt in view of the environment damage and evacuation of residents due to a large catchment area, known to be twice the size of Singapore. Chinese investments are high in Myanmar’s MNCs too. These investments, too, have had a widespread opposition from within Myanmar. China, however, continues pushing for it.

The other major projects that Myanmar signed with China are the Letpataung Copper Mine and the Sino-Myanmar Oil and Gas Pipeline. The Myanmar-China gas pipeline comprises the construction of two parallel pipelines for transporting crude oil and natural gas from Daewoo’s International offshore blocks A-1 and A-3 situated in Myanmar to China. This project, which was signed in 2004, came to fruition only when China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) signed a 30-year hydrocarbons sale and purchase agreement with Daewoo International in 2008.

While the gas pipeline became functional in 2013 the crude oil pipeline became operational in 2017, allowing China to import oil due to its growing demand, faster from Middle East and Africa. This project is in line with ‘China’s One Belt One Road’ initiative and will ensure in reducing the dependence on Strait of Malacca. Moreover, In 2018, the CNPC started looking for additional sources of natural gas in Myanmar to feed a pipeline between two nations. The firm is also building the liquified natural gas (LNG) terminal at the Made Island oil in the state of Rakhine, Myanmar.

For India, a worrisome development took place in January 2020, when Chinese President visited Myanmar and the two countries signed a slew of projects. One of the most worrisome aspect was the announcement of construction of the multibillion plan of the deep-water port in Kyaukpyu, which is a strategic port and too close for comfort to India. The port will be a threat to India because it would help China further its plans of encircling India. The port stands at the western-coast of Myanmar in Rakhine state, part of the special economic zone (SEZ) which is not too far away from India’s submarine base on its east coast close to Vishakhapatnam. In July 2020, Myanmar inked two electricity deals with Chinese LNG plants of total 580 megawatts. In case of a war, India’s options of war would get limited and presence in the Indian Ocean would be under severe scrutiny by China.

Another controversial project was the Leptadaung copper mine. The Wanbao Mining Copper Ltd in 2011 partnered with Myanmar’s military associated Myanmar Holdings Limited to take control of Leptadaung copper mine. Residents staged protests and eventually, it was suspended.

On how Myanmar’s position will help China assert influence, Joshi adds, “A Chinese gas and oil pipeline goes from Kyaukpyu to Kunming. This is beneficial to China as it avoids the Malacca Strait. China also wants to build a railway line from Kunming to the port it is developing there. So, it will be beneficial to China.”

The January 2020 Myanmar visit of Xi Jinping may have come as a comfort call to Myanmar because of the heavy criticism of Myanmar’s handling of Rohingya Muslims and China’s treatment of Uighur Muslims. While the West was critical of Myanmar, China was supportive. This fact may have drawn Myanmar closer to China.

However, in August 2020, Myanmar pushed back against China. The government opened up the Yangon-city Project, an important plan for the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor, which will connect Yunnan Province in China to Mandalay in central Myanmar, Yangon New City in the south and the Kyaukphyu Special Economic Zone in the west, to other foreign investments besides China Communications Construction Company (CCCC). This was done after a corruption scandal in the company came to the fore in other countries.

This maybe just a lone case of Myanmar resisting Chinese dominance in major investments and may not hold true for other cases. After all, China has serious strategic interests in maintaining a good relation with Myanmar. But this one instance does give India an opportunity to play its cards intelligently and not lose out to China in this game of strategic expansion.

Also Read: November 2020

Walking a Tightrope

The strategic position of Indonesia in the IOR makes it much sought after by both India and China

Also Read: October 2020

Why Thailand Matters

Its strategic location in the Indian Ocean makes it important to China’s maritime expansion plans

Also Read: September 2020

Gateway to the East

Myanmar is strategically important and India should get a strong foothold in the country

Also Read: August 2020

For Greater Good

Japan has changed its views on BRI and mended its relationship with China for economic reasons

Also Read: July 2020

The Himalayan Tango

China focuses on capacity building in Nepal

Also Read: June 2020

Vying for Attention

Sri Lanka’s strategic position in IOR makes it a much sought after ally for India and China

Also Read: May 2020

Chinese Checkers

India should regain its strategic position as an ally of the Maldives

Also Read: April 2020

Interdependent Neighbours

For years, the Indian foreign policy experts viewed China through the lens of encirclement. The theory of ‘strings of pearls’ was propounded to explain People’s Liberation Army Navy’s (PLAN’s) forays into the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). Here China cultivated a series of friendly ports all along the islands in the IOR to further enhance the endurance of its naval vessels. Indian experts argued that all this was aimed at encircling India and restricting the Indian Navy.

However, with the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, China has taken the ‘string of pearls’ theory to an entirely new level. It is no longer about encirclement of any one country, but creation of multiple modes of connectivity across the world — land, sea and digital — for greater cooperation. But can this cooperation be without conflict? This is the question that the world, including India, is grappling with.

This month onwards, FORCE starts a series in which it will look at India’s ties with the countries that have signed up for the BRI. This edition we start with Bangladesh.