Napoleon and the Advent of the Operational Art of War

Hersh Sewak

Berlin: It is the autumn of 1806. A small group from the Noble Guards of Prussia walk to the entrance of the French Ambassador’s house. Standing at the entrance, they unsheathe their swords and sharpen them on the stone steps of his residence. The Ambassador is safe. Hurting him is not the intention. This public display is for the Prussian monarchs to symbolize the coming war against France.

Prussia in 1806 included the eastern half of contemporary Germany as well as northern and western parts of contemporary Poland. These events took place before ‘national consciousness’ had taken root and therefore were intended for the Prussian royal elite.

Baron Marbot, a young French officer sent to Berlin witnessed this with nervousness. He had arrived a few weeks earlier bearing dispatches from Napoleon, now the Emperor of the French, for the King of Prussia. In Berlin, he witnessed this souring of mood among the Prussian elite. Now, he hastened back to Paris bearing a hand-written response from the Prussian King.

Upon arrival, he was ushered in Tuileries Palace where he handed over the letter to Napoleon. Upon hearing about the event in Berlin, Napoleon exclaimed, “The insolent braggarts shall soon learn that our weapons need no sharpening.”

Europe, 1806: The turn of eighteenth to nineteenth century had been tumultuous for Europe. The arrival of modernity signalled by the French Revolution had upended centuries of equilibrium. With it, war was unleashed with Republican and later Imperial France under Napoleon, who as the ‘Emperor of the Revolution’, arrayed against the monarchies of Europe.

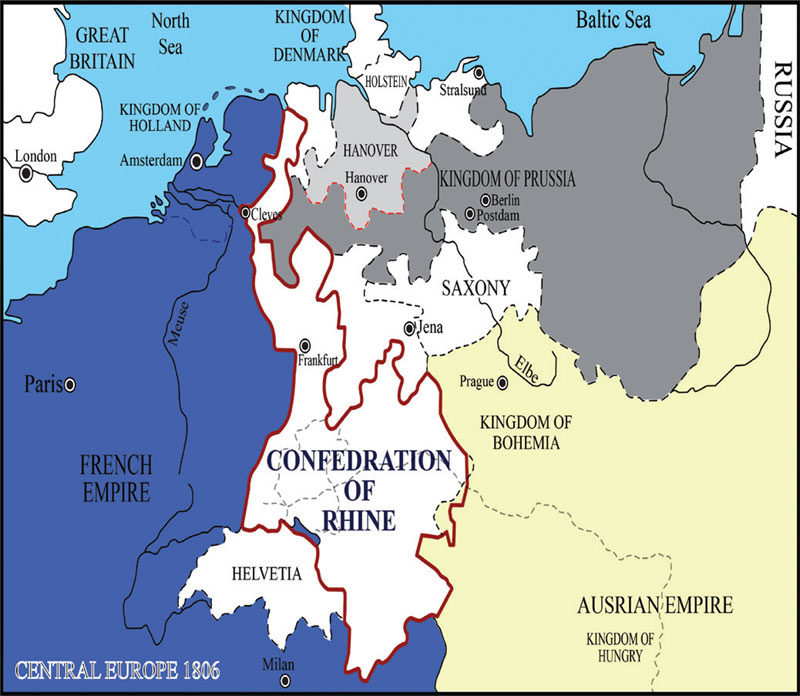

These wars commenced in 1792 had reached a critical juncture. By the end of 1805, the French had defeated the combined armies of Austria and Russia. Austria sued for peace while the Russian army hastened back to Russia. As a result, the French gained a new set of allies in Germany where Napoleon eventually replaced a millennia old Holy Roman Empire with a new entity, the ‘Confederation of Rhine’, with himself as its Protector. While Great Britain was distracted from European affairs embroiled in a conflict in South America, Prussia had not engaged in these wars since a brief intervention in 1792.

In spite of these victories, the strategic situation of France was not favourable for war. The French populace was weary of continuous warfare of last decade and a half. Thus, Napoleon sought peace with both Great Britain and Russia throughout 1806. He went even as far as offering the Prussian occupied territory of Hannover, given by him to Prussia earlier in 1805, to Britain as part of peace negotiations.

On the other hand, court intrigues guided Prussian strategy. The Prussian King cherished the secret hope that Napoleon will remain deterred by the prestige of the Prussian Army and that at some point, he would offer favourable terms. The Prussian Court remained a hotbed of intrigues with some advocating war while others arguing for the status quo. The news of Napoleon’s secret offer of Hannover to Great Britain gave the anti-French faction the upper hand. The Noble Guards put up the display of sharpening their swords to reflect this turn.

Consequently, Prussia mobilised its armies on 9 August 1806 while coming to an understanding with Russia. It would later issue an ultimatum on 26 September 1806 demanding a French withdrawal from Central Germany.

Napoleon met the prospect of war with Prussia with utter disbelief. He had earlier written contemptuously in a letter to his minister that, “The idea that Prussia could take me on single-handed is too absurd to merit discussion”. Out of caution, however, he had left the French Army stationed in southern Germany throughout 1806. He suspected possible double-dealing by Prussia. The eventual rejection of peace proposals by Russia on 3 September 1806 strengthened Napoleon’s suspicions of a new secret anti-French coalition.

Napoleon’s Grande Armée and the Corps d’Armée system

On 5 September 1806, Napoleon called for the mobilisation of 50,000 conscripts from the class of 1806 and the 30,000 reservists. On 18 September 1806, he received the news of Prussia’s march into the intermediate kingdom of Saxony and incorporation of the Saxon troops into the Prussian Army. This was tantamount to declaration of war and without delay, he issued about 120 orders and the ‘General Dispositions for the Assembly of the Grand Army’, the document that formed the basis of upcoming campaign.

The Grande Armée, as the French Army was called then, numbered 180,000. It consisted of six corps of the line, 32,000 cavalry and more than 300 pieces of artillery all together being eight numbered corps. They were further reinforced by 13,000 German troops from the Confederation of Rhine. These troops were organised under Corps d’Armée system. Corps d’Armée involved setting up of permanent formations consisting of infantry, cavalry and artillery supported by its own engineering, intelligence, medical services and its own headquarters.

The Grande Armée was commanded by Napoleon through Le Grand Quartier-Général or the Imperial Headquarters. It was an organisation to command the entire army in the field consisting of three parts:

- État Maison received all intelligence reports and arranged them for scrutiny by Napoleon;

- État Major de l’Armée, under the command of the Chiefs of Staff, received daily situation reports and delivered orders; and

- The administrative headquarters was tasked with issues of prisoners, wounded, administration and reinforcements. This was supplemented by presence of a standardized staff organised on the similar lines at the level of corps and further down the chain to the divisions.

Napoleon, for all his contempt of Prussia, did not underestimate its military threat and the preparations were made for a severe campaign. The goal of his preparations was to engage and defeat the main Prussian army before it could join the Russian army. By mid-September, the French army was fully mobilized. The Imperial Guard, then deployed in France, was sent down through wagon convoys covering 550 km in less than seven days. This is the only example of such a movement of large number of troops before the coming of railroads. Simultaneously, roads and settlements in Central and Southern Germany were reconnoitred. In response to the arrival of Prussian ultimatum on 7 October 1806, Napoleon marched the Grande Armée into Prussian held Saxony on 8 October 1806.

Prussian Army

Morale in the Prussian Army was high. It was well-drilled in formal tactics and ferocious discipline was imposed to achieve uniformity. Clausewitiz wrote, “When I draw a conclusion from all the observations that I have occasion to make, I always arrive at the probability that it is we who are going to win the next great battle.” The Prussian Army fielded a total of about 170,000 soldiers including, 35,000 cavalry and about 550 guns. However, about 80,000 soldiers were either left in garrisons or could not be called out.

The Prussian Army high command resembled more a council of war: divided in opinions, planning and war aims. It took the Prussian army almost a month and a half after mobilization to emerge into three field armies by the end of September 1806. Duke of Brunswick, appointed as the Prussian Commander, was unsure of the nature of the campaign. Later, his member of staff described, “I found the duke, as generalissimo, uncertain about the political relations of Prussia with France and England, uncertain about the strength and position of the French Corps d’Armée in Germany, and without any fixed plan as to what should be done… He had accepted the command in order to prevent war.”

The Prussian army, aware of the French military reforms, had introduced some piecemeal reforms inspired from the French. The new general staff was divided into three sections whose respective heads hated each other. Additionally, this general staff was not permitted to completely supersede the army’s Oberkriegskollegium, the body responsible for the military’s internal administration. The army lacked a staff corps that could coordinate and relay communications between the armies downwards to smaller formations. As a result, the Prussian High Command was compelled to issue elaborate orders going into details.

Jena Campaign

The Prussian army, in spite of early mobilization lost the initiative. Moreover, its leadership could not formulate a common plan of war with four competing plans being proposed. The final plan was a compromise reached by the King that pleased none.

The Grande Armée had already begun concentrating in southern Germany in accordance with Napoleon’s goal to secure a decisive victory by pushing the army deep into enemy territory forcing the Prussian Army to engage.

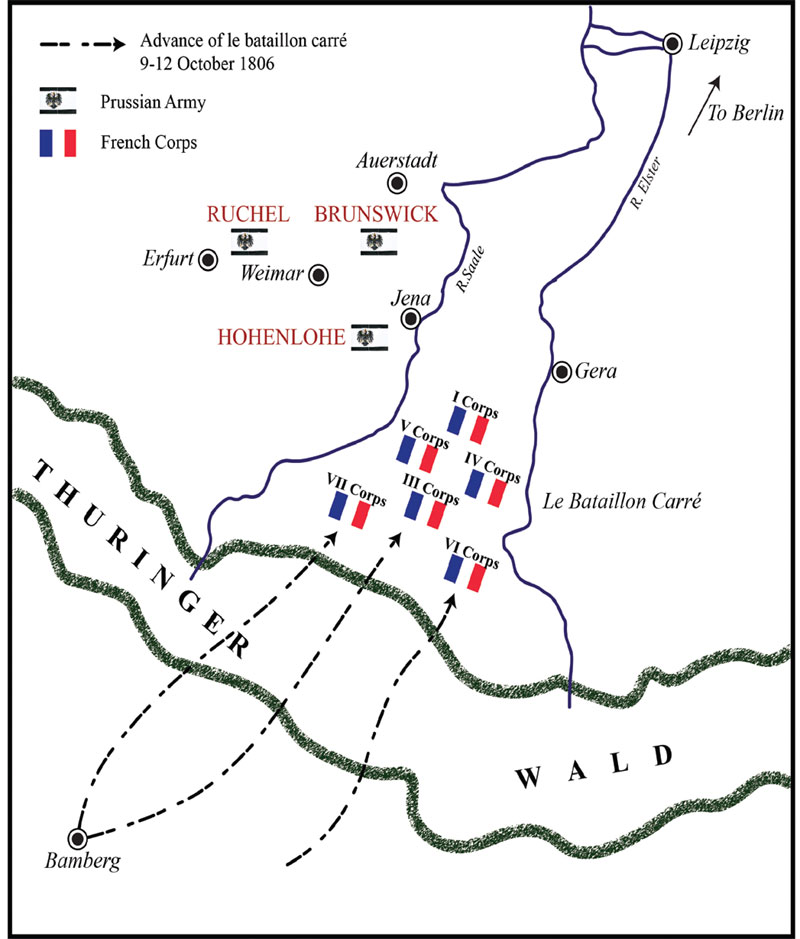

The French entered Germany from the south with the corps arranged in the le bataillon carré (the battalion of square), a diamond shaped rectangular formation. In this formation, the advanced guard was preceded by a screen of cavalry in the presumed direction of the enemy with a right wing, left wing and a rear guard with GQG in the centre. Each position could have had more than one corps with each corps being at a distance of 24 hours.

Throughout, the lack of knowledge of the exact movements of the enemy confounded Napoleon. On the midnight of 11-12 October 1806, he received two reports. They revealed that the Prussian Army had not fully understood his movements and were positioned to his west. In the next six hours, Napoleon issued series of orders to the corps to swing towards north east to take the strategic leftward turn and fall on the Prussian Army. The Grande Armée commenced on their execution within two hours of their arrival wheeling from the earlier advance from south to north towards an advance east to west.

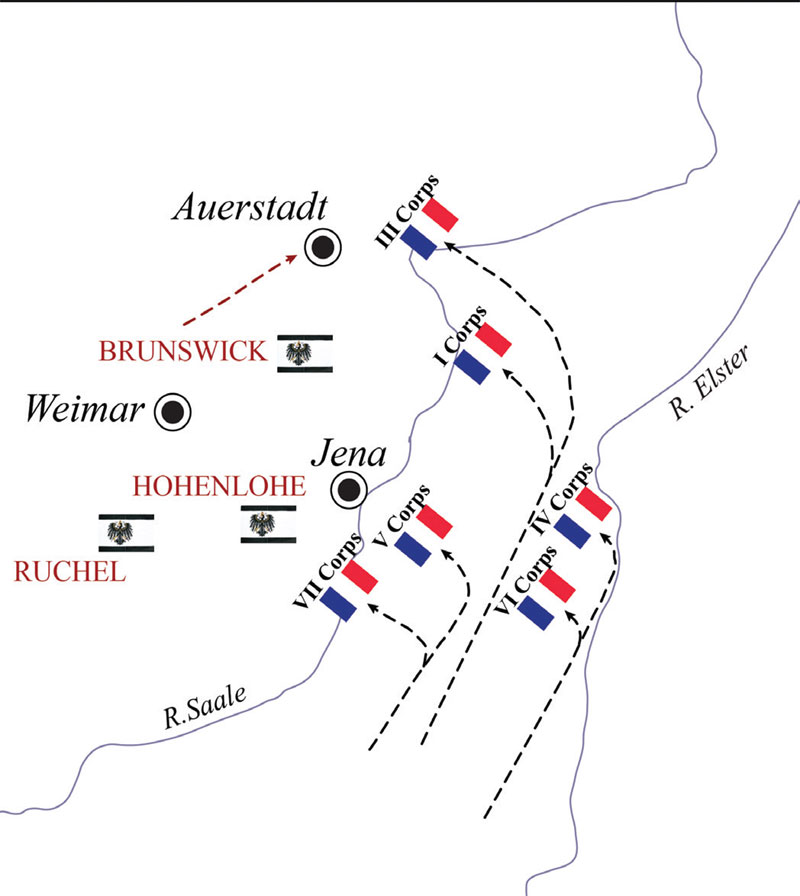

As the news of the French cavalry presence started to come in, the Prussian generals met in another war council on 13 October 1806. The French advance risked cutting the Prussian Army from its line of communication with Berlin. Finally, the Duke of Brunswick ordered the Prussian army to march backwards towards Berlin with his own army leading and Hohenlohe’s army to act as its flank.

Napoleon in his march towards west was still under the impression that the battle would not take place till the 16 October 1806. He did not know that the Prussians were much closer. On the night of 13 October 1806, however, he received reports from one of the corps that they had met the enemy at the town of Jena. Hearing the sounds of cannon, Napoleon realized his mistake and dictated a series of orders on saddle. All the corps were to concentrate at Jena. The battle commenced around noon on 13th October 1806 with about 21,000 French soldiers facing about 30,000 Prussians. However, in next 24 hours, the French concentrated about 145,000 troops and squarely defeating the Prussians. Marshal Davout took the laurels by defeating the main Prussian army under the Duke of Brunswick. The Duke had been retreating towards Berlin. Marshal Davout defeated him at Auerstadt, despite daring odds of more than two against one.

Following the defeat of the Prussian army at the twin battles of Jena-Auerstadt, Napoleon ordered one of the corps to continue the pursuit of the defeated Prussian army. The pursuit in itself formed the last part of the campaign. By 10th November 1806, the remnants of the Prussian Army surrendered to the French. In 33 days, Napoleon had defeated the Prussian Army.

On 24th October 1806, the French entered Berlin with Marshal Davout given the honor to lead the march. As for the Noble Guards who had brazenly sharpened their swords on the steps of the house of French Ambassador, they were marched before the same house as prisoners between two rows of French soldiers.

Enduring Insights for Modern Warfare

Napoleon was the first modern statesman and ironically, the last one that could command military as well as govern a state simultaneously. The days when the commanders would stand in the battlefield have since long passed. Yet, the key to the success of Napoleon was exactly this: his ability to command armies and set political strategy. He, thus, engaged with foreign states at all the three military levels: strategic, operational and tactical as well as politically. With one informing the other to make a wholesome assessment.

Thus, Napoleon understood the strategic possibility to secure peace with Great Britain and Russia throughout the year of 1806 aware of their inability to employ their military. Later, when Prussia did go to war, this political assessment led to the military goal of defeating the Prussian army before it could be reinforced by Russia.

Conversely, Prussia could not decide its strategic goal and when it did settle on confrontation, it went alone. Worse still, it could not translate this political decision into military objective wasting more than a month after mobilization. A realistic assessment of the French Army would have led to a more patient approach to unite with the Russian army. Even their commander, the Duke of Brunswick did not understand the political goals. Thus, the military plans were ad-hoc resulting from personal compromises. Prussian royalty chose a path that appealed to their vanity but kept them away from realities. Consequently, they faced Napoleon alone.

Modern warfare is this alignment between political goals and military possibilities. A modern leader succeeds only when he secures an open and realistic conversation on these two. An open one to not just hear what is appealing but what is needed without the burdens of fear, vanity and prejudice. A realistic one that eschews wishes in favor of evidence and strategic possibilities.

At the heart of this, lies the ability to either accept reality or live a lie. For political strategy and military preparations to have a successful outcome, they need to be based on evidence. To live a lie maybe the result of ignorance or a sense of denial but it leads to a path of self-destruction and humiliation. To accept reality is the skill and willingness to work with evidence and as the example of Napoleon shows, an insatiable need for evidence on and off the battlefield.

What has made Jena Campaign timeless has been the advent of operational art. In essence, Napoleon and Prussia saw and fought different wars. Corps d’Armée system and the Imperial Headquarters gave the French operational advantage that the Prussians simply could not match. Prussia, in effect, had lost the war before it was even begun.

The Corps d’Armée system enabled the Grande Armée to dominate a larger terrain on account of the ability of each corps to hold the enemy for twenty four hours. This larger spread of the army additionally enabled its rapidity in movements, as they could march simultaneously without clogging the roads. Each corps was interchangeable and overcame the need to be re-arranged when plans were modified. Thus, when Napoleon learnt the presence of the Prussian Army to his west, the bataillon carré simply turned with the tasks of each corps shifted from one corps to the other. The left flank became the center, the right flank became the reserve and the advance guard became the right flank. In other words, Grande Armée was conceptualized as an army consisting of self-sufficient and mutually-reinforcing corps that could spread out or concentrate operating under a unified command.

All this was supplemented by the Imperial Headquarters with staff organization connected down to the divisional level. This in turn enabled Napoleon to: first, supervise and control the movements of large number of troops, second, acquire and evaluate intelligence, third, maintain lines of communications over a large area. Therefore, Napoleon after learning of the location of Prussians could concentrate an overwhelming force within a day’s time. The staff through enabled the smooth carrying of these orders which in turn enabled rapid response.

On the other hand, the Prussian coordination broke down as the battles proceeded. The Prussian Army fought like an eighteenth century army dependent on the immediate number of troops. The orders issued by Prussian high command were lengthy in detail leaving scope for delay, confusion and miscommunication. The Prussian Army akin to museum of muskets was deadened by the memories of the past. Clausewitz put this bitter reality simply as, “below the fine façade all was mildewed”. The ‘all’ here were not the soldiers, who by all historical accounts and Napoleon himself admitting, performed exceedingly well. The ‘all’ was the manner, method and technique of fighting war.

None of Napoleon’s innovations were technological. They were conceptual. They were military ideas and concepts put into practice by incorporating them into the chain of command. All these put together enabled Napoleon to command an army the size of 180,000 troops. Their use ensured the French army a total and complete victory against a similar sized force fighting in its own territory in 33 days. The difference was in the operational art of war. In effect, Jena Campaign was a victory of a modern army over an eighteenth century one. Military leaders thus have a choice: to innovate and keep abreast of these advances or learn it with ignominy on the battlefield from a skilled opponent.

This ties in with the third insight. That braggadocio is not a substitute for actual capabilities. Napoleon too engaged in public displays. His bulletins of war were as much about informing the public as they were about building confidence. But they were done after the facts had become obvious and in keeping with the needs of the State. The Prussian royalty indulged their vanity when the hot-blooded Noble Guards put up the show of sharpening their swords at the house of French Ambassador.

To discerning eyes, callous displays reveal an attempt at substituting real capabilities with them. These attempts at papering over the disparities blind even the leadership to what is obvious. In a nutshell, the confident are free from the dependence of displays while the unprepared need this escape valve from confronting the coldness of facts. This the Noble Guards rudely learnt when they marched as prisoners of the victorious French Army in full view of the Berliners.

(The events are reconstructed relying on the works of leading historians and military theorists, specifically, David Chandler, Martin van Crevald, Peter Paret, Michael Broers, Philip Dwyer, Paul Schroeder, Steven Englund, and Charles Esdaile)