Agnipath is a bad scheme which is being marketed badly

Lt Gen HJS Sachdev (retd)

Lt Gen HJS Sachdev (retd)

Launched with much great fanfare, the Agnipath Scheme, has two major aims: to reduce the age profile of the armed forces, and to curtail the rising pension component, utilizing the savings for modernization.

The second component is not being accepted by the political class openly. This hesitation was visible during the press conference when the defence minister quashed the query of a journalist on the subject. Anyhow, there is no room for ambiguity and opaqueness when it’s a question of national security. The major takeaways of the scheme are as follows:

- The recruitment of Agniveers will be between the age of 17-1/2 to 21 (later changed to 23 for the first year). Presently, the recruitment age is from 18 to 21. The total vacancies released were 45,000, with a proviso that the same will be increased in subsequent enrolment.

The Agniveers will serve for four years. Thereafter only 25 per cent will be retained.

The Agniveers will serve for four years. Thereafter only 25 per cent will be retained.- During their tenure they will be entitled to a fixed monthly amount varying from Rs 30,000 in the first year to 45,000 in the fourth year. The present pay in the first year is approximately Rs 38,500 (includes Basic + DA + MSP). However, the take home will be Rs 21,000 (after forced savings of 30 per cent) in the first year and similar provision for later years. Similar amount (30 per cent) will be contributed by the government towards the savings and at the end of the tenure the outgoing Agniveers will be handed over an amount of Rs 11 lakh. The 25 per cent retained for regular service will not get anything apart from their forced savings.

- Agniveers will be insured at government expense for Rs 48 lakh.

- During their tenure, the Agniveers will be given 12th class pass certificates for their rehabilitation. A suitable quota will be reserved for them in CAPFs, DPSUs and other central and state governments jobs. Corporate Sector has also welcomed the move and expressed willingness, in fact in some cases, eagerness to take the Agniveers under their fold.

The Agnipath scheme is a major change in the recruitment pattern in the armed forces. It is likely to bring in combat effectiveness, human resource management and psychological displacement especially in the initial years. To focus on key issues, I have reduced the scope of analysis to army and infantry as it is the most affected. The Indian Air Force and the Navy being platform-based and relatively small in numbers are the least affected.

But before any analysis, it is imperative that we understand the current status, structure (of a combat unit) and system in vogue. The current authorized strength of the army has been taken as 12.5 lakh with an average yearly outgo of approximately 60,000 and corresponding intake of the same number. For the last three years no recruitment has taken place due to the pandemic. Hence, the current strength is in deficit by 1,80,000 (approximately 14 per cent). It has also been conveyed to the military that this deficit is unlikely to be filled thereby reducing army’s strength to 10.70 lakh.

The recruitment age before Agnipath was 18 to 21 years, nearly matching the newly announced scheme. However, under Agnipath, the soldier will actually become a regular after four years and serve as per the conditions thereafter; implying that his retirement age will be four years more in the rank he retires, as compared to today.

The strength of an infantry unit is 763. After the 3rd Cadre Review, this includes 60 JCOs, 131 Havildars and 206 Naiks resulting in a total of 397 higher ranks (rounded to 400) and 366 (rounded off to 370) riflemen/ sepoys. A rifleman serves for a period of 15 plus 2 years i.e., 17 years before retiring. Higher ranks retire in a graded manner from 22 years to 28 years of service.

For a soldier to be assumed as fully trained and experienced (to be a guide or senior partner to a novice), six-year service is a reasonable period during which he would have served in at least two different types of field areas as well as gone through one tenure at a peace station. He would have also undergone sufficient training in all specialist weapons at sub-unit/unit level.

Combat Effectiveness

Combat effectiveness is a product of various factors and not just age and fitness alone. They are the starting point and prerequisite for any army, but it includes numbers, the weapon systems in service, training, experience and lastly, but importantly, morale and motivation. Since the launch of the scheme all proponents for the scheme including the national security advisor, the defence minister, the serving military, senior veterans, some media channels and civil society, have been harping only on age and fitness.

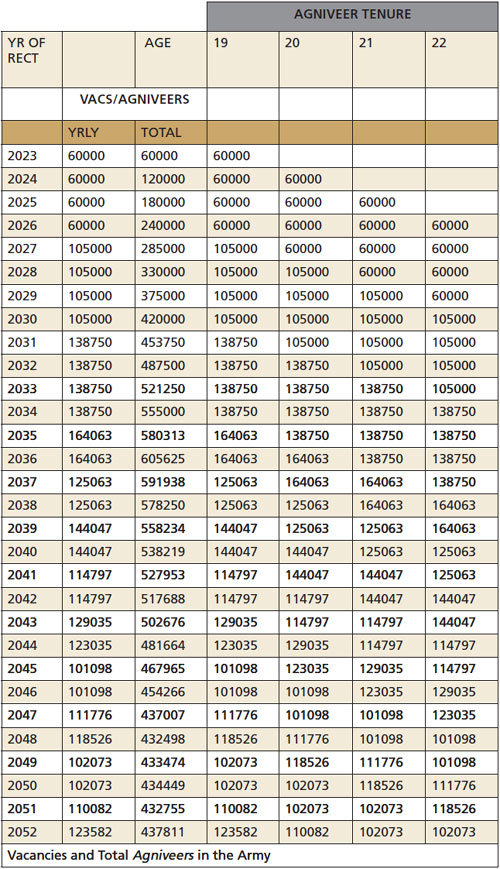

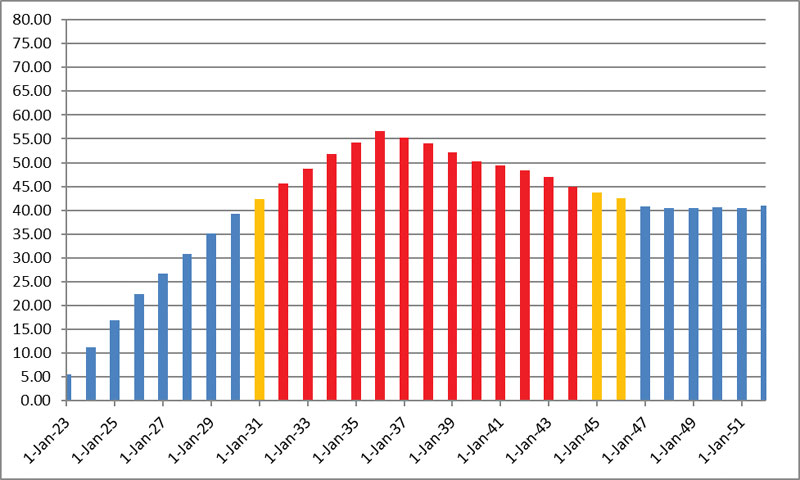

Numbers: The Agniveers will have little effect on the overall numbers, however, their component will keep increasing from 60,000 in the first year to 2.4 lakh in the 4th year i.e., 2026. It’s the classic ‘Push Model’ on display. After 2026, the intake will follow the ‘Pull Model’ since to keep the strength of the army at 10.70 lakh, there will be a necessity to compensate for the 75 per cent I (45,000) going out. Since this will continue to have domino effect, the total strength of the Agniveers will increase from 2.4 lakh (22 per cent) in 2026 to 4.2 lakh (39 per cent) in 2030 and 5.55 lakh (52 per cent) in 2034 as seen in the accompanying table. The peak strength will be reached in 2036 with 6.06 lakh. A whopping 57 per cent! Any attempt to cap the intake will impinge on the overall strength of the army.

Age: In its formal briefings, the army hierarchy has claimed that the average age of the soldiers will reduce from 32 to 26 years. However, a simple analysis shows that while the average age of riflemen will reduce from 27.5 to 20, the same will increase for the rest of the soldiers after 2036 since those regulars who would have come through the Agniveer way would be older by four years to their current equivalents.

With the ratio of 1:1 in the unit (post 3rd cadre review) it is evident that there will be no retirement in the rifleman/ sepoy rank after 17 years of service since all would have assumed higher ranks (with higher retirement age) contrary to current situation. Thus, in the long term there will be no conspicuous change in the age profile of the army. On the contrary it may increase after 2036. If this be true, then the question arises, why is the army hierarchy propagating this scheme under this garb?

Training

A fully combatised soldier is supposed to be ‘a killing machine’ and not a mere number. Present recruit training period is of 42 weeks which is proposed to be reduced to 26 weeks. It takes time to convert a young school going child into a soldier along with the satraps that come with it. Even 42 weeks is not enough and the young soldier on joining the unit is imparted further training to be able to carry out basic tasks. Any compromise on this aspect will put additional burden on the combat units and hamper their operational capability.

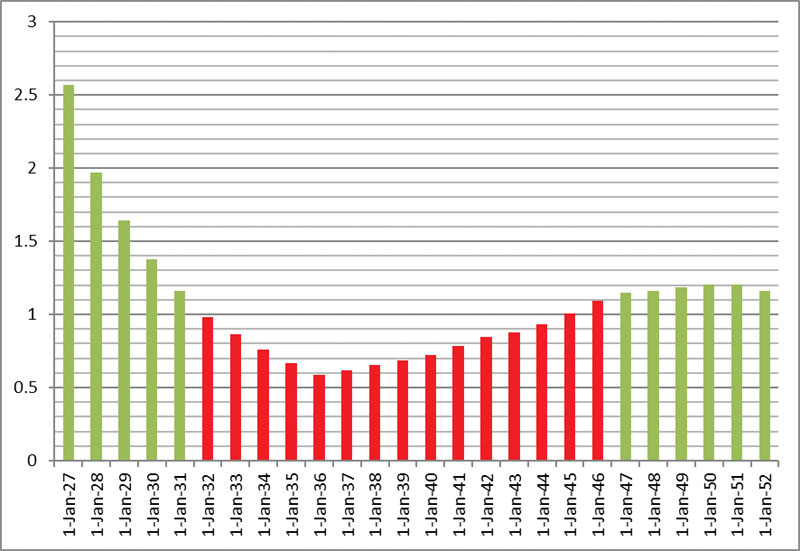

Experience: As brought out earlier, post 3rd Cadre Review, there will be approximately 370 riflemen/ sepoys (48 per cent) and 400 (52 per cent) other higher ranks in a unit. From the first table it is evident that the total number of Agniveers in the army will breach the 45 per cent mark in 2032 and stay above the mark until 2044, implying that all the riflemen/ sepoys in an infantry unit will perforce be only Agniveers. The question is what should be the minimum acceptable ratio of experienced soldier to an inexperienced soldier? Perhaps around 1.5:1, i.e., for every two Agniveers there are three experienced soldiers. Presently, it is in the region of 17:1 which drops sharply to 2.55:1 by 2027 and breaches the 1.5 mark by 2030. Since there has been no recruitment from 2020 to 2022, the experienced to inexperienced ratio gets into the unacceptable category of 1.2 or less by 2032 and stays in the red zone until 2046!

Modernisation: Arming and equipping a soldier with latest weapons and wherewithal is an operational imperative and in national interest. The concept of contact and non-contact warfare as a norm in the future was alluded to by the NSA in his TV interview, perhaps taking a cue from the current ongoing war in Ukraine. The implication is that in the future wars in the Indian context, the role of the soldier will be reduced as there will be requirement of non-contact weapon systems like drones, missiles, over the horizon weapon capability, cyber and space wars etc.

At my own peril, I dare say that the Indian context relates to fighting the war against China at the heights of over 14,000 to 15,000 feet in treacherous conditions. It cannot by any means be compared to the Ukraine war which is being fought in the plains. The combat soldier will still reign supreme and by no stretch of imagination should be downgraded in importance. Galwan is a recent example.

Financial Effect

The second aim of this exercise is to effect savings in salary and pension bill to enable modernisation of the armed forces. The current defence budget stands at two percent (all inclusive) of the GDP. The defence pensions take away more than 20-25 per cent of this budget which is high. Does the Agnipath scheme bring enough money on the table to justify its implementation in present form?

Defence Budget: Parliamentary Standing Committee is on record to have propagated that the defence budget should be 3.0 per cent of the GDP. Reduction in the allocation has a direct correlation with capital expenditure since the salaries and pension are fixed expenditure. The pension component also gets hyped in percentage terms due to reduced allocations. For example, 1.2 lakh crores pension bill is 22 per cent of the 5.5 lakh defence budget. However, it is only 18 per cent if the same is increased to 2.5 per cent of the GDP. The additional money will be more than adequate for modernisation.

Defence Pensions: This component includes pensions of defence civilians which forms approximately 45 per cent (Rs 54,000 crores) of the overall bill. However, it has been conveniently and deliberately suppressed since the current scheme does not address reduction of their share. If this component is separated out of the percentage of pension bill of the armed forces alone to the defence budget would be Rs 66,000-50,0000 crores.

Savings: The savings effected by induction of Agniveers will be on three factors. Savings in salary bill, outgo towards Agniveers after four years and the recurring pension bill. 60,000 will continue to retire until 2036 (current serving personnel). Therefore, there will be no savings in the pension bill till 2036. The current pay of a soldier is in the region of Rs 38,000 as compared to Agniveers’ pay of Rs 30,000. For the first four years the difference in pay will be the net savings of a total of Rs 576 crores in the first year and Rs 2,304 crores in the fourth. From the fifth year, the governments share towards 75 per cent outgoing Agniveers will have a negative impact on the savings. Net savings in the fifth year will be a paltry Rs 260 crores. In fact, there will be no savings from the year 2034 onwards.

The 3rd cadre review has increased the higher ranks considerably with an aim of every soldier to attain and retire minimum in the rank of Havildar. This has been done to improve the satisfaction level of every soldier in terms of pride, pay and allowances while in service and enhanced pension after retirement.

The only savings in the revenue expenditure of the army is going to be from the reduction of the overall strength from 12.5 to 10.7 lakh. The major takeaway from the above analysis is that if savings have to be made for modernisation, right sizing of the army is the area to focus upon and not bringing in some ‘hair brained scheme’.

Intangibles

The last and important factors of morale, motivation and stress are those intangibles that make a huge impact on combat effectiveness of the army and therefore need to be addressed too.

Morale: Col T.N. Dupuy in his book Numbers, Prediction and War mentions that morale is one factor that can have a multiplier effect on the overall force ratios between the adversaries and can alter the outcome of the battle or war. Similarly, there are numerous examples of battles lost because the soldiers morale was ‘in the boots’. What ensures high morale? It can be any number of factors, from being suitably armed and equipped to training, assured career progression, financial and social security.

The Agnipath scheme takes a hit directly from the last three factors: No career progression, no financial security since 75 per cent will be back to square one after four years and no social security as he will be back in the same environment but with the loss of four years in which his peers could have probably got educated, progressed in the chosen field and gained experience for better future. While the morale of the Agniveers may be high in the initial years of the contractual service, it will take a hit in the 3rd or the 4th year which will be spent in uncertainty and fear of failure.

Motivation: What motivates a soldier in laying down his life? The question has been more than adequately addressed by military historians and defence experts but still remains in the realm of the ‘unknown’. In Indian context, firstly, it is the ethos of ‘Naam, Namak and Nishan’. The pride and honour of one’s family, unit, regiment and nation. In all this, religion plays an important role. Every unit is bonded by religion or class and has functioned according to it. The war cries are peculiar and distinct for every regiment, with which the soldiers identify themselves. ‘Jo Bole So Nihaal Sat Siri Akal’ will motivate a Sikh but not a Rajput or a Maratha. Similarly, ‘Jai Bajrang Bali’ will not have the same effect on a Sikh soldier.

The NSA thinks it is a colonial concept and therefore needs to go. The bonding that develops between soldiers and between a soldier and his commander cannot be understood by a civilian. To a commanding officer, a soldier is like his son. This sentiment is reciprocated by the soldier. This unbreakable bond that lasts beyond service years is key to the answer to the question posed above. Some senior generals, both serving and retired, said on TV that the ‘army is not an employment generation scheme’, and ‘we will retain only the best’. They maybe right, but this line of thinking will deal a death blow to the bonding that goes beyond ‘being professional’.

Stress: The stress of the job, financial insecurity and social stigma are likely to be the most dominant factor in the last year of Agniveer’s tenure. Obviously, his focus will not be the same as desired. This is bound to have an adverse impact on the combat effectiveness of the infantry unit where approximately 90 to 100 personnel will be in this bracket.

Rehabilitation: A lot has been said about Agniveers being absorbed in CAPFs, central and state governments and the corporate sector. Rhetoric aside, the devil lies in the numbers to be rehabilitated. While the numbers may be manageable at 45,000 Agniveers after 2026, on annual basis the problem needs to be seen in totality. Don’t forget that getting jobs for 60,000 retiring every year currently is a huge task. Add to this 45000 agniveers and the number goes beyond one lakh per year!

Recommendation

Numerous examples exist of good products marketed badly having failed, but to have a bad product, marketed badly (read forcibly just because you have the monopoly), is a disaster. It is imperative that the powers that be go back to the drawing board, factor in all possible feedback and then relaunch ‘a scheme’ that caters to the needs of all the stakeholders. As the famous saying in the army goes: ‘Time spent on reconnaissance is never wasted’.

The need of the hour is to increase the defence budget to as close as possible to the recommendations of the Standing Parliamentary Committee and simultaneously undertake the task of ‘right-sizing’ of the armed forces.

Conclusion

National security cannot be left to the generals alone. But neither it can be entrusted to the political class alone. All policy decisions affecting national security having long term effect must be well thought through. Knee jerk measures will only bring in confusion and paint the decision makers in bad light not only internally but also internationally.

The present ‘premier launch’ of the Agnipath concept and its subsequent weak defence by the military leadership raises a very disturbing question. Has the last frontier of defence forces been breached and brought under the subjugation of the political class? It had happened prior to the Himalayan blunder of 1962. The fiasco that followed dented the national honour and psyche more than the physical humiliation.

The nation has once taken a knock and redeemed itself later against a weaker enemy. Any rap on the knuckles in the present geopolitical scenario will be a knock-out punch and all the dreams of becoming a regional or an Asian power will be laid to rest for the 21st Century.

(The writer is a former director general Assam Rifles. He has also been additional director general of military operation (Information Warfare) in Directorate General of Military Operations)