Pure guesswork is passed on to the forces in the name of intelligence in the LWE theatre

N.C. Asthana

N.C. Asthana

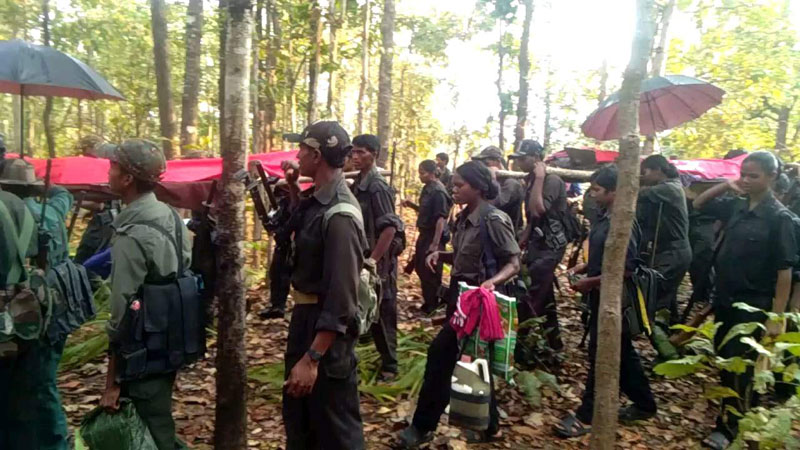

The recent Naxal attack in Chhattisgarh in which 23 men of the security forces were martyred has once again brought the issue of poor intelligence into focus. The attack took place just six km away from the nearest camp of the security forces and they were taken by complete surprise. No one had any idea that hundreds of Naxals could be lying in ambush so close to the camp, not to speak of having any idea of their weaponry or ambush tactics.

Obviously, this was as massive a failure of intelligence as it could be imagined. In any case, this is not the first time that the forces have been surprised. We have a long list of such disasters since 2010.

We do not need access to any secret official document to expose this farce of intelligence. A careful analysis of the operations in which the forces suffered casualties on a large scale speaks for itself. If, for the sake of argument, they had good intelligence, it would have resulted in some good if not spectacular operations. Since there have been no good operations at all, it only means that there is no intelligence worth its name.

Need for Actionable Intelligence

I am given to understand by officers who do not wish to be named is that these days troops go regularly into jungles because they are supposed to undertake operations, and obey they do, to pamper the vanity of senior officers. The senior officers, in turn, keep on selling pipedreams to the government that one major operation would finish Naxals and Naxalism both.

This ‘jungle bashing’ is called by fancy names like short range patrol, long range patrol, area domination exercise and the like. Huge operations involving thousands of troops are conducted essentially because they can be conducted, not because they ought to be conducted—it makes the senior officers feel like generals.

Every time, the troops are given some points on the map as the target for which the intelligence might have said that Naxals are present there. In the name of operational planning, senior officers simply plot the route to be navigated with the help of GPS. The troops are supposed to touch the points where most of the time they find nothing and come back; if their luck runs out, the Naxals ambush and kill them at the most unexpected places.

Anti-Naxal operations have therefore been reduced to essentially taking chances with their luck. Most of the time, any exchange of fire in non-ambush situations is actually a cleverly executed rear guard action by a couple of Naxals to allow the main body or leaders to escape safely—an action straight from Mao’s dictums.

Since the enemy is mobile and has no intention of fighting the troops on the terms of the latter, because the troops’ superior firepower would start telling, we can achieve any measure of success only if we have real-time intelligence on the Naxals’ movements and are prepared to keep on modifying our plans accordingly. Just marching up and down along fixed routes is as stupid as it can get.

Breeding Incompetence

The intelligence community cannot argue that their information was correct; the Naxals were there but ran away when they saw the forces from a distance. No, it is not so. Whenever, wherever there is a group of humans for some time, it does leave some trace of its presence, such as disturbed ground or vegetation, food items, Gutka pouches, evidence of cooking, some pieces of wrapping paper, etc. I am given to understand by officers that in most of the so-called operations, no such things are found. However, intelligence is the ‘holy cow’ and no questions are asked from ‘holy cows’.

From the outcomes of literally thousands of operations, one is forced to conclude that most of the information, which is passed on to the forces in the name of intelligence is pure guesswork or jargonized hearsay at best and outright cooked up stories at worst.

Challenges of HUMINT

Generation of genuine HUMINT (human intelligence) requires certain fundamental conditions to be met. If you have to have HUMINT of any operational value, your ‘agent’ must have ‘penetration’, that is, he must be in direct contact with the Naxals in the first place.

Second, it should be possible for him to pass on information in real-time. Third, he should be able to do it on a regular basis. Fourth, he should be located at a place where he may be contacted by the ‘handling officers’ easily. Fifth, he should not come under a cloud of suspicion in his organisation. There is nothing to suggest that the intelligence community has anybody meeting all these criteria.

The question is who could have such access or penetration and how could they be won over by the intelligence agency to become ‘conscious sources’ or ‘conscious agents’? Logistic providers do not fit the bill because every terrorist organization employs ‘cut-outs’. Moreover, they are often under over-watch by the Naxals. Arrested or ‘alienated’ cadres are of no use as they are denied any update.

One who could go where the Naxals happen to be must have earned the trust of the Naxals in the first place and should have a genuine reason to go there. An agent cannot simply walk to their hideouts. The biggest problem is to buy his loyalty or subvert him. Even if he is willing to accept money, it is a small world out there and he cannot ‘digest’ the money without someone noticing the new-found wealth.

Eventually, market gossip is window-dressed with jargon, and passed off as intelligence obtained from a human ‘source’, ‘agent’ or ‘asset’.

Limitations of TECHINT

Intelligence communities love to mesmerize their consumers through TECHINT (Technical Intelligence) and IMAGINT (Imagery Intelligence). These were once regarded top secret, but now even small-time politicians and journalists talk freely about them.

TECHINT/IMAGINT mainly consists of:

- Interception of wireless or telephone communications; and

- Imagery obtained through aerial platforms like drones fitted with optical cameras.

Usually, nobody would be fool enough to talk en clair over VHF or HF, knowing fully well that interception is so easy. In fact, if one is talking en clair, it means that he is deliberately planting misleading information. If they use some improvised code or some little-known language, it is difficult to decode it in real time.

In the Naxal operational areas, cellular phone coverage is very poor. Moreover, any terrorist organisation worth its name would take great care to ensure that the use of mobile phones (or for that matter, any communication device) by the members is highly restricted and monitored. Aman Sethi disclosed in his piece ‘The Many Lives of Gudsa Usendi’ written in The Hindu newspaper after direct interaction with the Naxals that they were aware of the connection between surveillance and communication.

It also means that even if a human agent has infiltrated them, there is no way he can communicate from where they are. He cannot keep on coming to towns without arousing suspicion. Thus, any intelligence officer who tells stories of his ‘source’ or ‘agent’ being ‘inside’ along with a group, is a crook whose only purpose is to siphon off secret service money in the name of the ‘agent’.

I am told by officers who did not wish to be named that the Naxals have started making fun of the Forces by planting sensational but false information.

No Strategic Intelligence Either

The stark reality of the vacuity of anti-Naxal operations is that even after suffering Naxalism for the past 54 years, the nation is still not able to answer two fundamental questions: the sources of strength of the Naxal movement; and its weaknesses.

More important than Naxal body count or arms recoveries made are the questions that are often left unasked: ‘Have we been able to weaken the movement materially? Are the Naxals on the run? Have we been able to strike at their vitals? Have we been able to disrupt the sources of supply of their arms and ammunition? Have we been able to disrupt their financial support systems? Have we been able to make them lose their popular support? Have we been able to make any inroads among the people from whom they draw their cadres?’

Unfortunately, the answer to most of these questions is a disappointing no. No agency can claim that it knows anything about them. The answer has to be in the negative because if they had answers to any one of them, certainly something could have been and should have been done in respect of some specific things in all these years!

Intelligence has managed to remain poor all these years because secrecy has become the permanent veneer to hide their epic incompetence. However, it is time that the people of the country ask probing questions from a system that has merely been groping in the dark for over half a century. Meanwhile, the soldiers continue to pay the price of their follies in blood.

(The writer, a retired IPS officer, has been DGP Kerala and ADG CRPF and BSF. He is author of 48 books including four on internal security)