In the din of war drums, the voice of a veer naari needs to be heard too

Shunali Khullar Shroff

Shunali Khullar Shroff

Twenty Indian soldiers and their commanding officer were killed in a brutal clash on 15 June 2020 in the Galwan valley. As terrifying details of the hand-to-hand conflict in which Indian soldiers were assaulted with crude and barbaric weapons emerged, most of us were left feeling indignant and anguished.

While there were some voices in the media asking for an economic boycott of China, there were more than a few wanting the Indian Army to give a befitting reply to China with an aggressive military response. This isn’t the first time that the Indian public and Indian news media have debated over a border conflict involving India and nor is it the first time that casual warmongering has taken place across our television channels and on social media.

Honour is important. Our national pride understandably demands that we ask our forces to go all out and give the enemy a bloody nose, but who ultimately pays the enormous price of war?

Is it the mother who will never see her 22-year-old son again? The 16-days-old daughter who will grow up without a father? Or the wife who did not realise that the last time she spoke to her husband would be the final conversation between them.

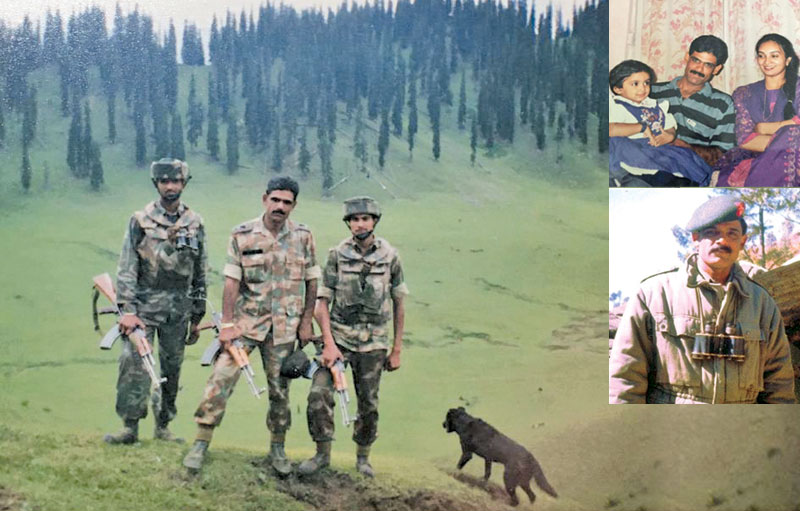

I spoke to Salma Shafeeq, wife of Major Shafeeq Mahmood Khan Ghori, who sacrificed his life on 1 July 2001 in Baramullah during Operation Rakshak, about the consequences faced by the family of a soldier killed in action.

You had been married only 10 years when your husband was killed in ops. Your children were only four and eight respectively. Can you take me back to that time and speak a little about it?

Our last family posting was in Amritsar in 1999. After that my husband, who belonged to 172 Field Regiment, was sent to serve 30 Rashtriya Rifles in Baramulla district in Kashmir. My children and I moved to Bangalore to the family accommodation to be close to my mother. I was only 19 when I got married and I had no idea what I was signing up for. I imagined a life full of good postings, parties and romancing around India.

At what point did you become aware of the sacrifices an army life called for?

In the beginning, it was difficult for me to accept the fact that my husband was constantly on the move. I was left alone for long periods when he would be on an exercise or in a field posting. There were no mobile phones then and I used to spend hours sitting by the phone waiting for his call. Then one day he sat me down and explained what it was like to be an army wife.

In the years that followed, he had many high-risk postings. Back then, Punjab and the Northeast were all dangerous places to be. Major Ghori served in Tripura, Punjab, and Kashmir. But with time I became strong. I knew he loved the country the most and his kids and wife came a close second.

Did you hear from him often when he was in Baramulla?

Whenever my husband was away from me, we would write to each other every day. He continued to write to me from Baramulla every day, and every once a week or longer, we would speak on the phone as well.

After coming back from one of his operations he told me that he had captured some militants who had ammunition on them. I was happy to hear that and hoped he would get an award for his bravery. The day he was killed and officers and their wives from the sub area came to inform me about his passing away. I thought they had come to tell me that he had been given a bravery award.

We spoke for the last time on 28 June 2001. I did not know he was going for another operation that day. As was my habit, I asked him if he was eating well and getting enough rest. He said kahan neend yaar, kahan khana peena, ham log bhatak rahey hain. At the end of all those conversations I remember, he used to keep saying ‘stay strong’. I never realised that he was preparing me for a future then that I had not yet foreseen.

How did you hear the news of his death?

Two days after we had last spoken, he died in combat on the morning of 1 July 2001. I had been living with my mother during the summer vacations. The landline hadn’t still been shifted to the new address and there was no mobile phone either.

The local army from sub area in Bangalore was trying to contact me since the morning. I returned to my accommodation with my children in the evening and I noticed that there were a lot of officers waiting outside. I thought they had come to give me the good news of my husband being awarded and the thought brought a smile on my face.

I went inside and started putting things in order when someone rang the bell and a stream of people started coming in. I still didn’t have a clue and kept smiling to myself, now sure of the good news I was going to get.

Then two ladies made me sit on the sofa and then sitting on either side of me, they held my shoulder and asked me when I last spoke to my husband. I told them it was two days ago and he had told me he was going to some jungles. I was going on and on proudly about how he had caught militants a few days back. And then they said, listen, your husband is no more.

I told them there had been a mistake. ‘No, no, my husband is ok. We have been speaking. You are surely mistaken,’ I said. Then they asked if they could speak to some other family members and I pointed towards the phone book lying near my landline.

My son was only four years old then. The next day, July 2, was his first day at school in lower kindergarden (LKG). I get goose flesh even today as I relive that day.

The next day, I went to the airport to receive him for the last time. This time he came in a box clad in the Tricolour. I also received his last letter on the day we did his last rites with military honours. I remember I kept begging my brother-in-law to open the casket to ensure that it was his body because I was in complete denial.

‘Just be strong and live life as though I am always around you. Never deprive yourself or the children of anything just because I am not with you’, my husband used to write to me in his letters. I always assumed that he was talking about his absence while on duty. After his death I realised that he was telling me something then, he was preparing for the future.

What do you feel as the wife of a valiant soldier when you hear all the talk about war, whether it is with Pakistan or with China?

I feel no child, no wife and no parent should go through the grief and bereavement one goes through when one loses their loved one to war. More than the gain, there are endless tragedies and loss that goes with it.

Civilians will not understand what that feels like for the family.

In fact, even my husband used to say that unless and until there is a war and army people make sacrifices for you and beat the enemy, only then our civil counterparts will understand the importance of the Indian Army because they think our life is all about fun postings, parties, socialising and the good life.

What has Major Ghori’s supreme sacrifice meant to you?

As a brave soldier’s wife, I am wearing his cap on my head in a way. It is a proud feeling. I think of myself as his stronger half, not his better half because I am literally in his boots. I took up everything from where he left.

Even now after so many years when I wake up in the morning, I get the thought that he is no more and today is another day that I have to live life without him and carry out my duties just as he would have wished. The army has taken great care of me. My husband’s brother and other officers have been like my family, always ready to help.

But I have had to play the dual role of father and mother. I have felt let down by the government when I had to run around government offices for paperwork for years. They have no empathy. They do not bother. Those are the times when I have wondered why my husband had to lay down his life for these people who have no empathy in them and who do not value his sacrifice.

I do not want any widow to go through all that I have gone through in all these years. Whether her husband died in action or not, I do not want them to suffer. Even now I am helping a 26-year-old jawan’s wife who is going through so much pain. Her husband died in training and her life is stuck because of the complicated paperwork involved. I am trying to help her get educated now by raising whatever money I can. She is only a school pass-out and has children to look after as well.

You have turned your tragedy into a mission by helping wives and children of martyred soldiers get back on their feet. To reach out to bereaved families and to take away their pain because you have been through it yourself is an extraordinary act of human kindness.

That is the only thing that makes me sleep well at night. These women live in villages. They are often very young and uneducated. Sometimes getting their paperwork sorted so they can be given the pension that is due to them can take years. But I do everything within my means to help them with that.

While the army gives you enough to secure yourself financially as a widow, it can get complicated when the government offices get involved. For instance, the state government has still not given me my dues. They had promised to give me some land. But in 19 years so many directors have come and gone at the Sainik Board—they are the ones who have to resolve this—but nothing has been done. Even the defence minister in 2015 had said on a news channel that he will get all the pending cases resolved within 15 days. I am still waiting.

Does a soldier die for his battalion or for his country? Whose loss is it when a nation loses a soldier?

The soldier dies for his nation. By doing so he makes his battalion and his family proud. But ultimately at a personal level, it is the family’s loss. Every time we lose a soldier, all the other families, including mine, go back to our own pain and relive it all over again. For us, the statement that time heals doesn’t hold true. The grief keeps coming back. I had to do a counsellor’s course before starting to counsel others because I used to keep revisiting my own grief.

What is the one thing that you as the proud wife of an officer who died for his country would want to say to the nation?

I want to say that our army is the strongest in the world. Our saviours are those who are serving and guarding us 24×7 around all the territories leaving the comfort of their homes and families. We need to stand by them and pray for them and for those who have passed away defending us.

Each and every citizen of the country should be grateful to them and their families and acknowledge their sacrifices. The families of soldiers killed in action carry a huge burden of grief on their shoulders. Hence, make things easier for them. The sacrifices of our men in uniform should not go in vain.

I want to add one more thing. Colonel Santosh Babu’s family received Rs 5 crores, a job letter and land. I commend the government on the prompt action on Col Babu’s case. I am happy for his family. But what about the 19 jawans who were slain in Galwan? Why can’t we treat their sacrifices at par? Death is a leveller. They all died for one country. Shouldn’t the families of other soldiers too get equally compensated? They come from economically backward backgrounds; from villages, some very remote. Why do everything for just one family because it will make headlines in the press?

(The writer is a daughter of a colonel who fought in two wars. A freelance writer, she is author of two books. Salma Shafeeq is working with the widows of both army and BSF jawans. Those interested in reaching out to her can write to FORCE)