Too many reviews, too little learning

Pravin Sawhney

On the 25th anniversary of the Kargil conflict between India and Pakistan, the question to ask is, did India’s military leadership learn the correct lessons? A good way to approach this subject is to go back to the primary source: the then Indian chief of army staff, General V.P. Malik’s book titled Kargil: From Surprise to Victory.

According to Malik, “Kargil was a limited conventional war under the nuclear shadow where space below the threshold was available, but it had to be exploited carefully.” The general raises three doctrinal issues.

One, Kargil was a limited conventional war;

Two, space for conventional war was available below the threshold nuclear war; and

Three, since the available space was not defined by either side (it would vary from sector to sector on the 776 kilometre Line of Control and the international border), both sides would need to be careful to not cross the other’s red line for use of nuclear weapons.

Interestingly, these assumptions were accepted as doctrinal truism against both adversaries (Pakistan and China) and were not war-gamed by subsequent military leaders. Therefore, the present concept of building ‘integrated theatre commands’ under the chief of defence staff aims to integrate the army, air force and the navy for joint operations under a limited war.

War doctrines are dynamic; they should evolve with the science (infusion of technologies) and art (concepts to optimise infused technologies) of war. This is what generalship is all about. Ironically, Malik’s doctrinal thinking should have been rejected right when it was articulated since it was fundamentally flawed.

Let’s start with his first assumption on Kargil being a limited war. Now, there is a big difference between war, conflict and grey zone operations. War is when both or all sides bring their full military might to the battlespace to accomplish what was not possible by negotiations. On the other hand, a conflict is when full military might not be brought on the battlespace, and grey zone operations refers to all activities and violence below the threshold of the use of firearms. It becomes clear that conflict is a gamble with firearms, where one or both sides believe, for reasons, that an escalation to war will not happen. All conflicts are aberrations, and hence doctrines for war cannot be built on them.

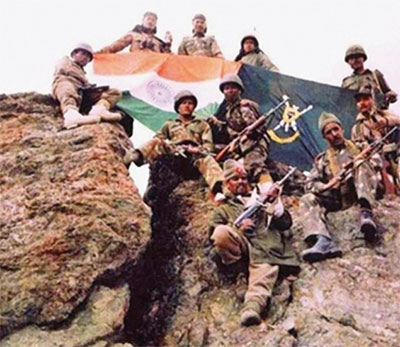

Thus, Kargil was a conflict since Pakistan brought minimal regular military in the battlespace that gave India the option to use its military assets unconventionally. Pakistan, under General Pervez Musharraf injected five battalions of its then paramilitary, the Northern Light Infantry (NLI), a brigade worth of regular troops to provide covering fire, and Mujahids in the conflict. The Pakistan Air Force, the Pakistan Navy and most of the Pakistan Army were not even in the information loop of the General headquarters (GHQ) to maintain secrecy. Only four headquarters, namely, GHQ, Rawalpindi corps headquarters, Force Command Northern Area (responsible for Siachen), and ISI headquarters were to execute the operation.

On the Indian side, all three services were involved in the operation. The Indian Army operation was called Operation Vijay, the Indian Air Force’s (IAF) was named Operation Safed Sagar, while the Indian Navy, which was on war alert, called its activities Operation Talwar. Under Operation Vijay, five infantry divisions and 100 artillery guns (many used in a direct firing role as enemy air defence and air force was not active) were inducted in the battlespace, while the holding or pivot corps were ordered to be on high alert. Malik gambled in assembling 100 artillery guns since they were pulled out from strike corps denuding them of firepower. This showed the poor level of war preparedness and nervousness of the army leadership to reclaim territory occupied by Mujahids at the earliest. At the beginning of the conflict when tactical intelligence on the enemy was unavailable, the army leadership, in panic, ordered units to climb heights to clear Mujahids occupying them. Of the 545 soldiers’ lives lost during the conflict, maximum casualties were in this phase. Then, there was acute shortage of war withal (ammunitions, spares and so on) at the height of the conflict in June 1999 with Malik publicly telling the media that “we will fight with whatever we have.” This showed poor generalship since it is well known that given General headquarters Rawalpindi’s major advantage of it alone deciding on when and where to start the war with India, the Indian military should be always prepared for war.

To dwell further on Malik’s limited war concept, it cannot become a doctrine since all wars are different. On the one hand, a war between peer military competitors (India and Pakistan), and between unequal military powers (India and China) will not be the same. Even between India and Pakistan, a war depends on each sides’ war aims, preparedness for war, comparative advantages at strategic and operational levels of war and generalship. For this reason, professional militaries test doctrines and war concepts by a mix of simulations, war games and realistic exercises with troops. While this has never been done to put Malik’s assumption to real test, the present military leadership is building integrated theatre commands on another wrong assumption that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the Pakistan military war concepts being similar will allow switching of Indian formations from one theatre to another with a different adversary.

Worse, after the war, the most important lesson should have been to build credible conventional war deterrence (capabilities and capacities) to prevent misadventure by Pakistan. The Indian Army, instead, convinced the political leadership to do the contrary: raise a new 14 corps headquarters for war, and raise more Rashtriya Rifle units to pursue counter terror operations more vigorously. This way, the army created more posts for senior officers, while doing more of the same on the ground.

Let’s now discuss Malik’s second doctrinal assumption on linkage between conventional and nuclear wars. Sadly, both Pakistan and China understood the lessons of the Cold War on this subject, which Malik and Indian military leadership still do not know it. In the Fifties during the Cold War, the United States (US) realised that, though technologically inferior, the Soviet Union had more conventional weapons (more tanks, more guns, more aircraft and so on) than Nato forces. To offset the advantage of the Soviet Union, the Pentagon initiated its ‘first offset strategy’, which introduced tactical nukes in battlespace. The thinking was that tactical nukes would halt the Soviet’s conventional blitzkrieg, and as the US had far more strategic nukes, the Soviets were unlikely to escalate. Then by the Seventies, the Pentagon assessed that the Soviets had comparable capabilities in both strategic and tactical nukes, which made first use of tactical nukes by Nato risky. Hence the need for Pentagon’s ‘second offset strategy’, which was based on long range precision fires to stop the Soviet advance well before the tactical war was joined. The lesson which came out of the two offset strategies was this: nuclear and conventional deterrence are not linked. They have to be built separately.

V.P. Malik is on extreme right accompanied by his wife

For this reason, after India’s nuclear tests in May 1998, the Pakistan Army chief, General Jehangir Karamat, ignoring US pressure and allurements to not follow India’s example, did nuclear tests of its own. Karamat said that these were necessary to maintain strategic balance with India. In other words, strategic and conventional war deterrence are separate. Moreover, when the Indian Army announced its Cold Start doctrine, supposed capability to cross over into Pakistan territory at zero notice, Pakistan, within months, said it had full spectrum nuclear deterrence, which included tactical nukes. The latter are not for use, but, given the short time needed to cross into Pakistan territory, tactical nukes are meant to deter India from exercising the zero-notice option. Another example of this truism is in the West Pacific where the PLA and the US military are locked in a security competition. Here, given its small numbers compared with the US military, the PLA is furtively building its nuclear arsenal, knowing well the need for separate nuclear and conventional war deterrence.

Thus, Malik’s assumption of linkage between nuclear and conventional wars is wrong. The way to deter conventional war is by building deterrence for it. Moreover, when the deterrence gap is hugely disproportionate, as in the case of the PLA and the Indian military, the PLA, should it decide, will not hesitate to wage an occupational war like reclaiming Arunachal Pradesh which it calls South Tibet. The PLA has enormous capabilities to neutralise India’s meagre nuclear capability for its conventional, non-strategic (tactical) and strategic means.

Coming to Malik’s third assumption, between peer competitors like India and Pakistan, Rawalpindi is unlikely to gain much by a conventional war with India. This explains why it has been waging a proxy war in Jammu and Kashmir since 1991. By doing this, the Pakistan Army has made two major gains, one known and the other unknown. The known one is the slow bleeding of the Indian Army, where India is losing its trained young soldiers to nameless and faceless terrorists with no loss to the Pakistan Army which continues with its war preparedness. And the other equally dangerous loss is the intellect freeze of the Indian military leadership. For a professional military to follow the US military’s war concept of the Eighties, called Air Land Battle (1986), shows that the leadership has, for 37 years, not done its job, which is to follow the advances in warfare and accordingly prepare credible deterrence. How is then the intellect of a general and a young officer any different? It could be argued that the general has more experience, which, to be sure, makes him better for handling tactical situations, not for conceptualizing campaigns against the PLA. India’s primary adversary, PLA is also at the cutting edge of war. The fact that not a single military officer has questioned Malik’s doctrinal wisdom is evidence that senior military leaders read very little and think even less. No wonder they are not confident about speaking their minds to the political leadership.

What is the way forward for the Indian military to build credible deterrence? With two adversaries, it would be advisable to focus on the primary threat, namely, the PLA since deterrence against it would deter the Pakistan military too. Against the PLA, it would be better to concentrate on conventional deterrence, and not on building nuclear and conventional deterrence simultaneously. China, like India, follows a no-first use nuclear policy, which means it would not use nuclear weapons first or together with conventional weapons.

The PLA follows an asymmetric conventional war strategy with two simultaneous phases: One for the battlespace where combat happens (combat zone), and the other for an enemy’s whole-of-nation operations (war zone) to disrupt normal civil life. PLA’s strategy for combat zone is called “systems destruction warfare” where the focus is to deny information to the enemy by destruction of its networks, communication nodes and command and control centres. Without information at all levels of combat, the enemy would be rendered blind and deaf leading to chaos in the battlespace, which in military parlance is called command breakdown. In the war zone, the aim would be to throw normal life into chaos by cyberwar, satellite destruction by space war and denial of internet by snapping subsea cables coming into India. The overall purpose of both operations would be to end war with minimal casualties to the PLA.

Since the Indian military is three decades behind the PLA in technologies and war concepts, it would need to prioritise acquisition of technologies, as well as draw a roadmap for building credible deterrence. For example, technology areas requiring immediate attention would be offensive cyber and electronic fires, electro-magnetic spectrum management, long range precision fires and capabilities to ‘look deep’ inside enemy territory. Alongside, there will be the need for employment of artificial intelligence in both combat services and combat. While all this is about capability building, credible capacity building (defence industrial complex) in select areas to meet a surge of war would also be necessary.

All this will take time. Hence, the need for doable statecraft to ensure that peaceful answers are found for the two military lines. Either the military lines with Pakistan and China should be resolved, or they should be made peaceful for an extended period of time.

Timeline Kargil 1999

The Pyrrhic Victory

3 May: Local shepherds report the presence of Pakistani Mujahids.

5 May: Indian Army sends patrol in response to earlier reports; Five Indian soldiers captured, and later found dead.

6 May: The first intrusions in the Kargil sector are detected.

9 May: Indian Army’s ammunition dump in Kargil is hit by the heavy shelling by Pakistan Army.

10 May: Multiple infiltrations across the Line of Control (LC) are confirmed in the sectors of Dras, Kaksar and Mushkoh.

11 May: Indian Army’s Northern Command requests fire-support of Mi-25/35 helicopter gunships and armed Mi-17 helicopters from the Air Officer Commanding (AOC) HQ Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) to evict a few ‘intruders’ who had stepped across the LoC in the Kargil sector. The AOC J&K says that to get fire-support in the existing operating conditions, HQ Northern Command needs to approach HQ Western Air Command.

14 May: Vice Chief of Army Staff, Lt Gen. Chandrashekhar calls on Air Chief Marshal A.Y. Tipnis at Vayu Bhavan. He says that the army wants fire-support by Mi-17 helicopters. ACM tells him that government authorisation is mandatory for any IAF deployment on the LC.

Meanwhile, in Srinagar, General Officer Commanding, 15 Corps, Lt Gen. Kishan Pal tells the Unified Headquarters that “the situation was local and would be dealt with locally”. Based on this claim, defence minister George Fernandes tells the media that the infiltrators would be thrown out in 48 hours.

15 May: Lt Saurabh Kalia of the 4th Jat Regiment leads a routine patrol with five soldiers, sepoys Arjun Ram, Bhanwar Lal Bagaria, Bhika Ram, Moola Ram and Naresh Singh in the Kaksar sector. They are ambushed by Pakistani troops. Following a fierce fire-fight all of them are killed. Autopsies reveal that they were brutally tortured before being killed. Around this time, Indian Army troops deployed in the Kashmir Valley start moving towards Kargil.

25 May: The government allows the use of air power with two caveats: ground and air forces were not allowed to cross the LoC. Then Chief of Army Staff (COAS) Gen. V.P. Malik later wrote in his book, Kargil: From Surprise to Victory that, ‘I felt that the movement of additional units and sub-units at the brigade and divisional level had been done in haste. The hastily moved units and sub-units had neither adequate combat. Strength nor logistics support. They are being tasked at brigade and divisional levels in an ad hoc manner without planning the details.’

26 May: The Indian Air Force (IAF) begins airstrikes against suspected infiltrator positions.

27 May: The IAF’s MiG-21 and one MiG-27 fighters are shot down by Pakistan’s Army Air Defence Corps’ Anza surface-to-air missiles.

28 May: Pakistan Army shoots down IAF’s Mi-17 helicopter; four crew members are killed.

1 June: The Pakistan Army begins bombarding operations on National Highway 1 in Kashmir, almost cutting off road movement to Ladakh.

5 June: India releases documents recovered from three Pakistani soldiers establishing direct involvement of the Pakistan Army.

6 June: A major offensive by the Indian Army in Kargil begins.

9 June: In the Batalik sector, Indian troops reclaim two significant positions.

11 June: India releases intercepts of conversations between Pakistan COAS Gen. Pervez Musharraf, who was then on a visit to China and his Chief of General Staff Lt General Aziz Khan (in Rawalpindi), further proving Pakistan Army’s involvement in the conflict. Incidentally, as mentioned in the book Dragon On Our Doorstep: Managing China Through Military Power, China played an important behind the scenes role in supporting Pakistan. Chinese forces did offensive patrolling in Ladakh ensuring that India does not withdraw the acclimatised troops of 114 Brigade at Dungti for Operation Vijay against Pakistan.

13 June: Tololing in Dras is secured by Indian forces after vicious fighting.

15 June: United States (US) President Bill Clinton tells Pakistan Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif to pull all the troops and irregulars out of Kargil.

16 June: National security advisor Brajesh Mishra meets his US counterpart Sandy Berger in Europe. Tells him that it is difficult to leash the Indian military forces for long.

29 June: Pakistan Army begins slow retreat from select mountain peaks in Kargil under pressure from their government, even as the Indian Army begins advancing towards Tiger Hill.

4 July: Dreading the conflict escalating into a nuclear war, President Clinton invites Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif to the US and pressurises him to order the army’s withdrawal to the LoC.

5 July: Sharif officially announces Pakistan Army’s withdrawal from Kargil. the same day, the Indian Army takes control of the peaks overlooking Dras, bringing peace to the beleaguered town.

7 July: The mountain peak point 4875 is recaptured by Indian troops at great loss.

8 July: Another peak, Tiger Hill is successfully recaptured by the Indian Army.

14 July: Operation Vijay is declared successful by Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee.

26 July: Government officially announces the victorious end of the Kargil conflict. Asserts that the entire area has been cleansed of Pakistan’s irregular and regular forces.

1 September: Indian Army raises new 14 Corps at Leh (Ladakh). COAS Gen. Malik says, “We need a credible dissuasive posture in Ladakh till the LC and the Siachen dispute with Pakistan and the boundary question with China is fully resolved.”

—Compiled by Eliza Rizwan