A year after the Wuhan summit, it is becoming clear that China bested India

Pravin Sawhney

Pravin Sawhney

One year ago, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had travelled to Wuhan for the informal summit with President Xi Jinping. Sold in India as Modi’s initiative to ‘reset’ or normalise ties with China after the 72-day Doklam stand-off, the Wuhan summit was the consequence of China’s successful military coercion. The summit paved the way for China’s entry into South Asia. And with India’s assistance.

Speaking on Doklam at the Institute of Chinese Studies on 27 September 2018, former eastern army commander, Lt Gen. Praveen Bakshi who oversaw the stand-off said that compelling the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to build defence habitat and forward deploy its troops in harsh climatic conditions of North Doklam and the Line of Actual Control (LAC) was a gain for India. Hitherto, while Indian troops held the LAC round the year, the Chinese, with excellent infrastructure on their side, came in vehicles to patrol the LAC.

What escaped Gen. Bakshi was: What if the PLA’s military objective for starting the Doklam face-off was to create conditions for permanent forward deployment and training of its troops? Doklam was carefully chosen by the PLA in the hope that Indian Army would escalate matters, which it did. This made it easier for the PLA to renege on two articles of the 1993 and 1996 agreements.

Article II of the September 1993 Agreement stipulated that, ‘Each side will keep its military forces in the areas along the Line of Actual Control to a minimum level compatible with the friendly and good neighbourly relations between the two countries.’

Article IV of the November 1996 agreement said that, ‘The two sides shall avoid large-scale military exercises involving more than a division (15,000 troops) in close proximity of LAC. If either side conducts a major military exercise involving more than one brigade group (approx. 5,000 troops), it shall give the other side prior notification.’

The raising of the Western Theatre Command (WTC) under President Xi Jinping’s 2015 military reforms against India had necessitated intensive joint training of thousands of PLA troops close to the LAC. Earlier, the LAC was held by Chinese border guards (rough equivalent of India’s paramilitary forces); focus was on building infrastructure for rapid induction (by land and air) of large PLA forces (between 32 to 34 divisions) into Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR); and surveillance of the LAC was largely by technical means. Training for war in high altitude and mountainous terrain was not a PLA priority.

This changed with the WTC which involved transformational structural and organisational changes. In his 2018 New Year message to the PLA, Xi Jinping, as the commander-in-chief, had exhorted them to strengthen training and be prepared for war. Similarly, in the official PLA Daily newspaper editorial on 1 January 2019, training and preparation for war were listed amongst the top priorities for China’s military.

By inducting large troops on TAR after Doklam, the PLA achieved two objectives. It could do the desired training for war. And it raised the threat level for India: from border management to forces-in-being. Border management threat implied tactical alterations on LAC like border transgressions. Credible forces-in-being suggest capabilities for war.

Between June and December 2017, the PLA built a permanent presence in North Doklam and TAR with the construction of helipads, upgraded roads, pre-fabricated huts, trenches, shelters and stores to withstand the chill in the high-altitude region. Its troops, already at height from 10,000 to 16,000 feet on TAR were acclimatised. From the earlier six to eight Combined Arms Brigades (CABs), the numbers shot up to about 13 CABs on TAR. Each CAB, depending upon whether it is light, medium or heavy, would have between 6,000 to 8000 troops and accompanying paraphernalia. The PLA had within months of crisis permanently deployed (with appropriate accommodation, defence works, and equipment) about 500 soldiers just 150m from the stand-off site, about 2,000 troops in North Doklam with Yatung, the largest town in Chumbi Valley, having about 6,000 troops.

This worried the Modi government. With general elections approaching, Modi sought informal meeting with Xi. Meanwhile, foreign secretary, Vijay Gokhale initiated a series of actions to indicate conciliation towards China. The cabinet secretary through a note asked senior leaders to not attend Tibetan Thanksgiving events planned in March 2017, and the MEA-funded IDSA think-tank was instructed to cancel the Asian Security Conference which had China as the theme at the eleventh hour.

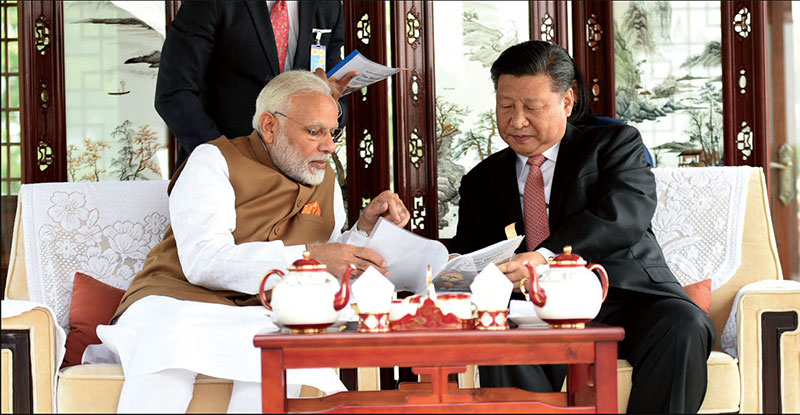

Modi met Xi on 27-28 April 2017 in Wuhan. The joint statement underlined that both leaders had given strategic guidelines to their militaries for peace on the LAC, and had agreed on strategic communications — euphemism for how the two sides could accommodate each other’s concerns. Within days of the Wuhan summit, Modi held another informal summit with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Sochi. Since Putin is the only world leader capable of influencing Xi, he was sought by Modi to perhaps be the guarantor for peace on LAC.

A key thing to come out of the Wuhan summit was disclosed by Chinese ambassador in India, Luo Zhaohui, who had participated in the summit meeting. Speaking to The Tribune (1 October 2018), he said, ‘China-India Plus can be new model in South Asia.’ He gave the example of India-China-Afghanistan, India-China-Nepal and even Bhutan where India could assist China since it does not have diplomatic relations with the Kingdom. Given the massive infrastructure-building technology gap and deep Chinese pocket, the trilateral cooperation to help small nations would automatically make China the leader.

For example, all nations in South Asia with exception of India and Bhutan have signed up for the Belt and Road Initiative, whose apparent focus would be on infrastructure building. This brings China in South Asia. To check whether India would abide by the Wuhan spirit, China has reportedly suggested October 2019 for the second informal summit where Xi would be pleased to come to India. India now faces the catch-22 situation: with Chinese forces-in-being on the LAC, can it wriggle out of the Wuhan spirit that it has signed for strategic peace.