How Adivasis are being pushed out of their jal, jungal and jameen. An extract

Freny Manecksha

In September of 2011, Linga was arrested on charges of acting as a courier between the Maoists and the Essar company that has many business interests in the state. Essar had built the 267-kilometre-long pipeline carrying iron ore slurry from Kirandul to the port of Visakhapatnam, which had been breached by Maoists in many places.

In September of 2011, Linga was arrested on charges of acting as a courier between the Maoists and the Essar company that has many business interests in the state. Essar had built the 267-kilometre-long pipeline carrying iron ore slurry from Kirandul to the port of Visakhapatnam, which had been breached by Maoists in many places.

Soni, who was co-accused in the case, was arrested a month after Linga. In the Dantewada police station, where she was held under police custody, she was stripped, tortured and was subjected to sexual violence with stones being inserted into her vagina, at the behest of police superintendent Ankit Garg, according to her petition. This bold declaration with detailing of torture led to an inquiry initiated by the apex court and the medical examination in Kolkata confirmed the allegation. Eventually given bail, she was acquitted in all eight cases. On 22 March 2022, she was found not guilty in the last case filed by the Dantewada police in 2011. ‘Can they give the twelve years back to me? Was her statement to the press. Anil Futane was also arrested on charges of being a Maoist. Acquitted in 2013, he died shortly afterwards, whilst Soni was in jail, of serious neurological complaints, sustained perhaps because of the savage physical assault he underwent in prison.

In her small home in Geedham, Soni recalled her days in jail, not in terms of suffering, as I thought she would, but as spaces of learning. ‘The state thought they were imprisoning me but jail became my training ground. I gained valuable lessons; every inmate’s story was like the study of a new subject. I realized that the only way to live was for one’s people’.

Why did she term her earlier life lalchi (greedy)?

‘I was self-indulgent. I wanted material comforts, good clothes, a fashionable saree, matching hairpins. I wanted to do up my home. Life revolved around me and my family. I didn’t know better…’

Jail brought her, she explained, a much better realization of herself as an Adivasi, a political understanding of her community’s suppression and the socio-economic dynamics of the state.

‘I knew a little about the Salwa Judum and their fight against Naxalites before going to jail because as a teacher with knowledge of Hindi, I used to be approached when the police picked up civilians. I would intervene with huge trepidation. Bahut darr tha. Police ko dekhte hi mein bahut darr rahi thi’ (I was very scared. Just seeing the police filled me with huge fear).

Behind bars, she says, she not only lost this fear but realized the real intent behind the confrontation between the Judum and Naxalites. She understood the reasons behind the destruction of the Adivasi way of life, of how rapacious greed for minerals and control over land (jameen) is the overriding force that has spelt so much suffering for her people.

‘I would brush my teeth in the morning, have a bath and then sit down with my sister inmates for lengthy conversations. That is how I came to understand the pain of my people in Bastar, the creation of the Salwa Judum, the Maoists, the nature of sexual violence used as a weapon against women. The fake encounters, the killings. Had I not been sent to jail I would never have been the kind of person I am today.’

Termed a lone crusader, a cause celebre, Soni shot into the limelight, even in international circles, because of the way she spoke out during her ordeal in prison and after her release. There is criticism that she does not head a movement, that she has not built up an organization and works alone: she says she prefers to be perceived as someone who identifies with her people’s suffering. Her ability to articulate these concerns and need for support after incarceration and repeated attacks on her, probably impelled her to join the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP). Although she lost the elections, she continued as a member of some years.

Her decision to leave AAP in 2019, she said, was because Adivasis were increasingly voicing their disenchantment of anyone associated with political parties and rather than be identified as an AAP politician she wanted to be considered a social activist.

Even her critics, political and others, cannot fault her courage and matchless energy. Her phone rings all the time. The demands are many: someone is picked up and the village wants her to locate the person and thana; a fake encounter has taken place; savage beatings have occurred, and the village would like to record the case even if it means carrying the injured on their backs to Dantewada; people have been granted bail but need sureties. Fielding calls, rushing to affected villages, she is always on the move.

I met her in February 2021, after she was recuperating from a head injury sustained when she fell off a motorcycle; she had also suffered form Covid. Still weak, she was nevertheless back in the thick of action. She showed me a video clipping of a protest in Narayanpur she had attended two days earlier, where song and dance was being used to reinforce the Adivasi battle cries. Some 28,000 people had gathered in January, she told me, to signal their discontent with the lease given to the Jayaswal Neco Company for prospecting in the Amdai Ghati pahad (hills), which is sacred to Adivasi beliefs.

‘Jal, jungal, jameen hamara hai…’ (The waterbodies, jungle and the land… belongs to us). Transcending cliches, the Adivasi battle cry makes an assertion for the vibrant, pulsating ecosystem of their communities. In this way of life, the community is vested with stewardship of the water resources, the forest and the land. They own nothing; they hold everything that matters in trust for the future. It is this belief that has shaped the contours of Adivasi culture and now Adivasi resistance.

Drawing from images of the natural world, Soni articulated her own concerns with the paradigms of ‘development’, modern-day education and the obliteration of Adivasi identity, all of which are interlinked.

What was her vision for her people in this twenty-first century? Harking back to a halcyon childhood, she recalled: ‘I walked with my mother till late at night in dense jungle with no fear. We lived in such harmony with all those hundreds and hundreds of trees. Now we live in fear. Everything is at risk—these trees, the waters, our mountains, our stones. Even our insaniyat (humanity) is under attack.

‘Shiksha or education is extremely important but, how does it benefit us when children are taught to embrace alien concepts and models that reject our own knowledge systems and moral values? Adivasi children reside in hostels where discourse revolve around building highways and broad roads to facilitate mining and our displacement. How do Adivasis, as forest-dependent communities, benefit from this model of development? Why do we need such broad roads that spell destruction of our forests?

‘Our values and way of life are scorned and demeaned. We are portrayed as people who hunt, as if it is a sin. There is no understanding of why we hunt and how we hunt nor is there any acknowledgement that our vision has an innate respect for all life. Adivasis in the pahads (hills) acknowledges the bear has the right to live as much as them, their instincts for survival and loss of fear is developed with the hunts. Present-day schooling is alienating our children for this ecosystem. They no longer want to go into the wilderness.’

She spoke with dismay of children returning home without acquiring the basic skills of agriculture, of how to plough fields, collect firewood. ‘I went to school (an ashram school known as Rukmini Adivasi Kanya) but, in our days, we learnt all that. I see educated youths playing with cell phones and lolling around at home while their aged parents work. They tell me that they are studying and don’t need to know how to sow seeds or plough and will instead do naukri (get a job). As what? As a chaprassi (a peon), is the answer.’

Also disturbing for many Adivasis, is the obliteration of their culture through appropriation and imposition of culture. ‘Children are told to celebrate Diwali, Holi, pay obeisance to Sita Mata, contribute towards a Ram Mandir and made to forget their own gods and goddesses. Even our politics is now subsumed into the Hindutva agenda,’ said Soni.

Soni was alluding perhaps to the manner in which the Hindutva ideology has permeated to such an extent that even the Congress-led government of Chhattisgarh has drawn up a Ram Van Gaman project with construction of some fifty-one temples along the sites of the Hindu deity Ram’s path as depicted in the Ramayana. Hundreds of Adivasis and in particular the Gondwana Ganatantra Party, under the late tribal leader Hira Singh Markam’s aegis, staged a protest against the move. They blocked the highway on 17 December 2020 saying these projects lay in the vicinity of Adivasi areas and their sacred hills. Adivasi organisations argued that implanting the project through government machinery would violate the secular principles of the Constitution.

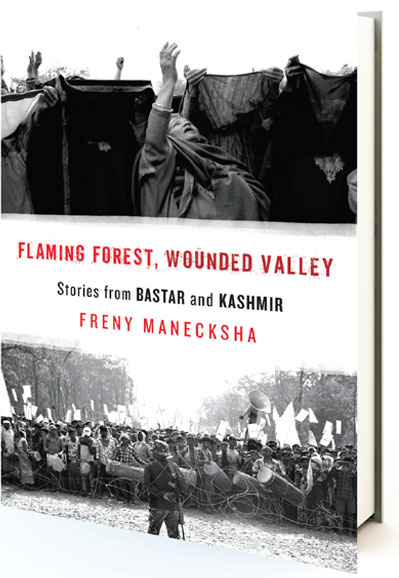

FLAMING FOREST, WOUNDED VALLEY: STORIES FROM BASTAR AND KASHMIR

Freny Manecksha

Speaking Tiger, Pg 296, Rs 599