How Nehru sought unity in the diversity of Hindus and Muslims. An extract

Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee

Nehru understands the impact of Islam in India and of Indian Muslims as a flowering (and deepening) of a cultural identity that is unique. He writes in The Discovery, ‘An Indian Christian is looked upon as an Indian wherever he may go. An Indian Moslem is considered an Indian in Turkey or Arabia or Iran, or any other country where Islam is the dominant religion.’ One may ask: How vague or concrete is this Indianness of the Indian Muslim? One of the answers Nehru provides is:

Nehru understands the impact of Islam in India and of Indian Muslims as a flowering (and deepening) of a cultural identity that is unique. He writes in The Discovery, ‘An Indian Christian is looked upon as an Indian wherever he may go. An Indian Moslem is considered an Indian in Turkey or Arabia or Iran, or any other country where Islam is the dominant religion.’ One may ask: How vague or concrete is this Indianness of the Indian Muslim? One of the answers Nehru provides is:

The fierce monotheism of Islam influenced Hinduism and the vague pantheistic attitude of the Hindu had its effect on the Indian Moslem. Most of these Indian Moslems were converts bred up in and surrounded by the old traditions; only a comparatively small number of them had come from outside.

Ambedkar speaks of ‘incomplete conversions’ and finds it a ‘mechanical cause’ behind the common characteristics between Hindus and Muslims. His reading of Ernest Renan, on what makes a nation, made Ambedkar conclude something quite different:

In depending upon certain common features of Hindu and Mahomedan social life, in relying upon common language, common race and common country, the Hindu is mistaking what is accidental and superficial for what is essential and fundamental. The political and religious antagonisms divide the Hindus and the Musalmans far more deeply than the so-called common things are able to bind them together.

Is Nehru’s historical understanding regarding the deeply layered identities of the Hindu and the Muslim superficial?

The problem with Ambedkar’s historical judgement is that it weighs too much on the politics of nationalism (what he calls ‘political’). Once the idea or claim of nationalism gets divided on religious lines, the truth of history doesn’t matter very much.

Ambedkar is arguing on the basis of the Muslim League’s reading of India’s history and its Muslims. The League is more interested in carving out a distinct political cause rather than establishing historical nuances.

Ambedkar, however, gives the stern reminder that ‘[whether] the minority is a community or a nation, it is a minority and the safeguards for the protection of a minor nation cannot be very different from the safeguards necessary for the protection of a minor community’. The necessity is facilitated by what Ambedkar calls—borrowing the phrase used in various ways by Western political thinkers from Alexis de Tocqueville to John Stuart Mill—the ‘tyranny of the majority’. If a community, be it a potential nation or only a minority, has a ‘minor’ status, it must be protected from majoritarian power. Ambedkar’s argument that the ‘minor’ in any form—community or nation—holds the right to safeguard its identity is a politically ethical one. His political sociology, or his exaggerated reasons behind Muslims being another nation, remains contentious.

Nehru’s historical point may be less political but no less real for the lack of it.

A political point of difference between Nehru and Ambedkar is that Ambedkar, despite his problem in recognizing the Indianness of Islam, backed the Muslims on the question of minority rights. Nehru, who was more welcoming of the Indian variety of Islamic faith, was uncomfortable granting Muslims the status of politically vibrant minority. This difference was due to Ambedkar’s willingness in granting political autonomy to the community, which Nehru was against.

In his letter to the chief ministers on 20 September 1953, Nehru wrote:

[A] more insidious form of nationalism is the narrowness of mind that it develops within a country, when a majority thinks itself as the entire nation and in its attempt to absorb the minority actually separates even more. We in India, have to be particularly careful of this because of our tradition of caste and separatism. We have a tendency to fall into separate groups and to forget the larger unity.

This is a perfect instance to understand the roots of Nehru’s ambivalence. He realizes how majoritarianism poses a threat to a diverse and secular nation by its mono-cultural project. The politics of sameness intensifies separation. In the desire for a ‘larger unity’, the reality of twoness is not just emphasized but found undesirable.

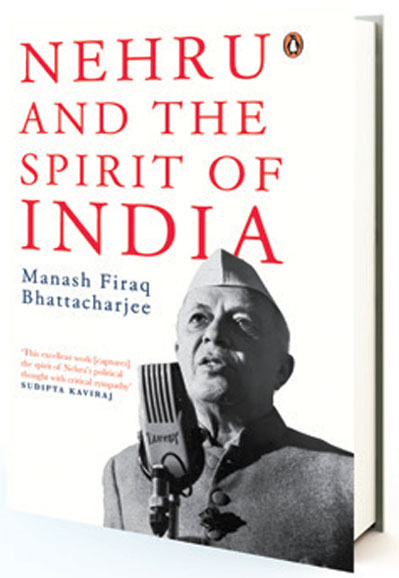

NEHRU AND THE SPIRIT OF INDIA

Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee

Penguin Random House India, Pg 248, Rs 599