How the 1970 elections sowed the seeds of the Bangladesh liberation war. An extract

This chapter follows the early years of Pakistan, the challenges of governance in a state constituted by two widely separated and culturally distinct territories, and some of the failures that led to separatism in the Eastern wing. It covers the general elections of 1970, the victory of the Eastern-based Awami League and the Pakistani refusal to honour the election result.

This chapter follows the early years of Pakistan, the challenges of governance in a state constituted by two widely separated and culturally distinct territories, and some of the failures that led to separatism in the Eastern wing. It covers the general elections of 1970, the victory of the Eastern-based Awami League and the Pakistani refusal to honour the election result.

In Pakistan

The roots of what is now Bangladesh’s desire to separate from what was originally West Pakistan go back to the time of Partition itself, to 1947. Pakistan was created in two geographically separated and culturally distinct regions, at the time West Pakistan and East Pakistan, nearly two thousand kilometres apart, with post-Partition India squarely in between. The population of East Pakistan was actually greater than that of West Pakistan; during Independence, there were around forty-two million people in the East against thirty four million in the West. But political power and major institutions of the government were concentrated in West Pakistan and dominated by its people.

These unpromising factors were the starting point for many genuine challenges of governance, but there was no shortage of man made and self-inflicted challenges as well. Budgetary discrimination began almost immediately after Independence, as the federal government of Pakistan invariably allocated well over 50 per cent of spending to West Pakistan. East Pakistan, with 55 per cent of the population, never received more than around 45 per cent of government spending, and in some years, only a little over 30 per cent. And even beyond the skewed allocation of spending, there was a structural lop-sidedness to the economy. Industrialization in West Pakistan was disproportionately dependent on the exploitation of raw materials such as jute and cotton from East Pakistan.

There was also severe language discrimination. In 1948, the federal government of Pakistan proclaimed Urdu to be the sole federal language of the country, and began to remove the Bengali script from state documents, currency and stamps. (Without trivializing the issue, it is a matter of faith in most of India that when dealing with a Bengali, the last thing you want to do is to disrespect their language.) Immediately, a powerful language movement against linguistic discrimination sprang up in East Pakistan. It enjoyed near complete popular conviction in the East.

Beyond language, there were also ideological and cultural differences. Most West Pakistanis looked down on Bengalis as a supposedly non-martial race, sparsely represented in the military— there were only 300 East Pakistanis among the 6,000 officers of the Pakistani Army. They also saw Bengalis as somehow lesser Muslims, because of their cultural, linguistic and social affiliations with Hindu Bengalis, and a perception that their Islam was ‘contaminated’ by its long coexistence with Hindu cultural and social practices. The federal government, dominated by Pakistanis with roots in the West, failed to address these issues; indeed, they sometimes deliberately exacerbated them.

Over the next couple of decades, a few East Pakistanis, such as Khwaja Nazimuddin and Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawadi, did manage to ascend to prime ministership or other positions of political power in Pakistan. But the West Pakistani establishment found ways to depose East Pakistanis elected to prime ministership in short order, and they generally did not serve out their full terms.

Skipping to 1969, in March of that year, the government in Pakistan was assumed by the military (not for the first or the last time), through the unusual mechanism of an ‘invited’ military coup. General Agha Mohammed Yahya Khan assumed the office of President and chief martial law administrator, while announcing his intention to return to a representative form of government, with a constitution to be devised by ‘representatives of the people elected freely and impartially on the basis of adult franchise.’ These good intentions were formalized in the Legal Framework Order (LFO) of 1970, and the scheduling of general elections later that year. The newly elected National Assembly, which would for the first time reflect population distribution in terms of having more seats representing East Pakistan than West Pakistan, was intended to be tasked with drafting a constitution.

In December 1970, at the elections, the leading East Pakistani political party, the Awami League, won a landslide victory, taking 167 of the 169 seats in the East. It thereby secured an absolute majority in the 313-seat National Assembly, and with it the right to form a government, not just for the Eastern wing but for the entire country. This was a much more significant victory for the Awami League than Pakistani authorities in the West had anticipated. It was, in fact—some contemporary Awami Leaguers admit—even more comprehensive than the League themselves had anticipated.

The West Pakistan-based Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), then a relatively new political party with eighty-one seats in the National Assembly, came to be the second largest, although with not even half as many seats as the Awami League. The brilliant and charismatic former minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was its founder. Over the next few months, the PPP, together with—it has to be said—the largely unstinting support of other West Pakistani parties, simply refused to convene the National Assembly, effectively preventing the Awami League from forming a government.

This refusal to honour the election result was greeted with outrage in East Pakistan—an outrage many in India genuinely shared. India’s own democracy was young; its Constitution had barely passed its twentieth birthday; but many in India felt a genuine, sincere sense of bewilderment that influential politicians could refuse to recognize the results of an election. [The infamous Emergency, and its brief suspension of the constitutional and electoral process in India, was still a few years into the future—and the attempted autogolpe of January 2021 in the US half a century ahead.] Ham-fisted handling by the West Pakistan-dominated federal government of cyclone-relief measures, following the November 1970 cyclone in the East, exacerbated the outrage there.

At this stage, Pakistani conspiracy theorists notwithstanding, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the fiery and inspirational leader of the Awami League, was actually not seeking a complete breach with the rest of Pakistan. A number of alternative schemes were discussed between West Pakistani and East Pakistani leaders, which might have prevented a definitive break. These included separate Prime Ministers, a coalition government, a scheme for autonomy generally referred to as the Six Point scheme, and others. But by March 1971, negotiations were on the point of breakdown.

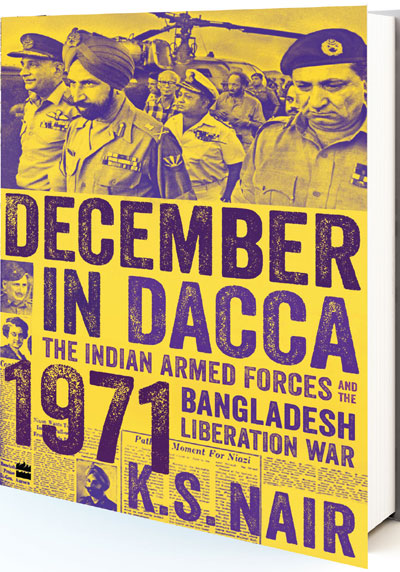

DECEMBER IN DACCA: THE INDIAN ARMED FORCES

AND THE 1971 BANGLADESH LIBERATION WAR

K.S. Nair

HarperCollins Publishers, Pg 344, Rs 699