How extremists use music and poetry for indoctrination and mobilisation. An extract

Kunal Purohit

Kunal Purohit

Kamal urgently wants to rewrite history in a way that benefits Hindu nationalists. He does this by reinventing the past and recasting inglorious events that painted Hindu nationalists in a poor light, by pitting historical figures against each other and urging his audience to discard icons who were critical of Hindu nationalism.

Travelling to smaller cities, mofussil towns and villages, Kamal carries the message of Hindutva through his craft. He helps to spread the ideology in areas where most mainstream forms of popular culture might not have the reach and, as a result, the same impact as his poetry could. Addressing dozens of such events each year since he started in 2017, Kamal has traversed across the northern, western and eastern parts of the country many times over, incidentally, the regions where the BJP gets the bulk of its electoral backing.

Through his work, Kamal makes his message simple to understand: conjuring up vivid imagery of a glorious past, painting the present to be abhorrent and stoking fears in his audience about a grim future.

He will ask seemingly straightforward questions. One of his most popular works focuses on the revolutionary Chandrashekhar Azad, titled ‘Chandra Shekhar Ko Kya Mila?, What did Chandra Shekhar Get’. In it, he juxtaposes how Azad died and has since been forgotten while Jawaharlal Nehru was rewarded with the Prime Minister’s chair. Between these selective, conveniently chosen comparisons lies his politics and its aims: such comparisons hide more than they reveal. His rhetoric, coupled with his powerful oratory in packed kavi sammelans, urges the listener to suspend reason and rationale and instead consume the emotion.

Kamal tells his listener how Azad was shot dead at the age of twenty-four by the British colonial police in the then-Alfred Park of Allahabad city. Azad had spent ten years in the country’s freedom struggle, starting with Gandhi’s Non-Cooperation movement and later joining the Hindustan Republican Association, an outfit formed by revolutionaries.

While he rightfully extolls Azad’s contributions, Kamal wilfully and carefully neglects any mention of Gandhi and Nehru’s contributions. He doesn’t mention anything that Nehru and Gandhi have done, none of their struggles, nor their time in prison during their decades-long involvement in the freedom movement.

Such poetry reduces complex historical issues, nuances and debates to binaries: pro-Hindu, good vs evil. Such binaries are easy for audiences to grasp since they don’t require any contextual knowledge of these events or personalities and, instead, appeal to their innermost emotional fears and the deeply submerged prejudices and stereotypes that they harbour.

Even the issues Kamal flags are taken out of the BJP and the Hindu right-wing’s playbook: from decrying the growth of Muslim population in India to stoking fears of threats to the existence of Hindus and Hinduism, to attacking liberal arts institutes like the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) to targeting Muslim film actors with malicious propaganda. Without declaring his allegiance openly, Kamal attacks all of the BJP’s rivals, from critics in the media to the Opposition political parties and leaders.

For Hindutva to survive and flourish, it seeks enemies, and hence, needs to constantly produce newer enemies. Kamal reinforces the old enemies, helps single out new ones and also helps the Hindutva ecosystem sustain both, the villainization of these enemies and the glorification of ‘real’ heroes, like Godse.

The role of poetry in political and religious mobilization is, often, overlooked. Poetry is seldom seen as a powerful tool for indoctrination, even though evidence is stacked in favour of this proposition.

One of the most popular religious texts in Hinduism is the Ramcharitmanas, a sixteenth-century poetic retelling of the epic Ramayana. It is possibly ‘the most influential religious text of the Hindi-speaking heartland’ with influence ‘far beyond’ this heartland. The poet and saint Goswami Tulsidas wrote it to serve as possibly the first written text that tells the story of Lord Ram; until then, the story was largely transmitted among people orally. The Ramcharitmanas changed that; it gave Hindus a document that ‘took the story of Lord Ram to every household in north and central India, creating an emotional connect between an average Hindu household and Lord Ram.

Even before the Ramcharitmanas, the Bhakti movement, a campaign to reform and challenge the caste hierarchy by ‘emphasizing the individual’s direct connection to god’, spread on the backs of poetry and the works of poet-reformers, from Guru Nanak and Kabir to Meerabai, Surdas and Chaitanya.

If these texts spurred religious mobilization, other poetic works helped political mobilization.

In the mid-to-late nineteenth century, poetry became a key carrier and disseminator of nationalism in the country as poets started expressing nationalistic sentiments by combining them with religious motifs to awaken consciousness among citizens. In 1870, poet Hemchandra Bandyopadhyay wrote a poem in Bengali titled ‘Bharat Sangeet’, Song of Bharat, which asked Hindus to ‘become experts in the deployment of weapons, go mad in the rasa of warfare’ against colonial forces. The poem gained wild popularity and became ‘the next great landmark in the nationalist literature of modern Bengal.’

Similarly, in the period immediately after the First World War, when the Khilafat movement, a pan-India movement among the Muslim community demanding the restoration of the Islamic Caliphate, gathered momentum, political poetry in Urdu was used to mobilize masses and spread political messaging about the movement.

Later in the twentieth century, when Prime Minister Indira Ghandhi imposed the Emergency between 1975 and ’77, blanking out free press and placing curbs on free speech and freedom of expression, thousands of poems by poets across the country circulated underground, many of which were ultimately published after the Emergency was lifted.

But not all mobilization done through poetry was for just causes like the overthrow of colonial rule or religious mobilization to end caste hierarchies. The Hindu nationalist movement also started eyeing the influence of poetry among the masses.

Academic Rosinka Chaudhuri found that Hindu nationalist poetry like Bhagat’s might have laid the foundation for the emergence of an organized Hindu nationalist force like the RSS, five decades later in 1925.

‘The Hindu Nationalist Movement in India, for instance takes as its starting point the year 1925, when the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh was first formed. The ideological developments in the nineteenth century that made it possible for such political formations to come into being, however were operating, at least in Bengal, from the 1830s onwards, when the idea of the Indian nation was still in its early stages of construction. It is may contention that certain influential ideas and images of the nation were envisaged in poetical practice long before such conceptions found currency in historical or political discourse in India.’

Much later, poetic rhymes were also used to a powerful effect by the Hindu right-wing during the Ram Janmabhoomi agitation, starting in the late 1980s. One slogan, especially, went on to become an impactful clarion call during the agitation:

Ram lalla hum aayenge,

Mandir wahi banayenge.

Dear Ram, we will come, do not fear,

To build the temple right there.

This slogan, coined at a Hindu right-wing rally during the movement in 1986, remains popular even now, inspiring scores of similar poems and songs.

Globally, too, poetry has been a potent tool in indoctrinating people with extremist ideologies. It remains little known, but the Islamist militancy has often relied on using poetry for propaganda purposes.

Some of the top leaders of Al Qaida, the terror outfit that was born in Afghanistan in 1988 and subsequently spread globally to attract members from various countries, including the West, were known to use poetry extensively in their speeches. A few, from Osama Bin Laden to Ayman al-Zawahiri and Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, even penned poetry themselves.

Researchers following this use of poetry in extremist indoctrination believe that the art form is well-suited for such use.

“This power of poetry to move Arab listeners and readers emotionally, to infiltrate the psyche and to create an aura of tradition, authenticity and legitimacy around the ideologies it enshrines make it a perfect weapon for militant jihadist causes,” writes academic Elisabeth Kendall.

“In the practical function of argument, poetry has the added advantage of papering over cracks in logic or avoiding the necessity of providing evidence by guiding an argument into an emotional rather than intellectual crescendo”, she adds.

Much of poetry’s power to be used as an effective tool of propaganda to further such extremist ideologies comes from its ability to be able to construct ‘an enemy’ through its words and the imagery it conjures. To quote Kendall:

‘There is no clear original jihadist identity, only a constantly repeated imitation of the idea of the original. Poetry helps to create this, for example by referencing heroic figures from Islamic history, employing well-known tropes (such as referring to jihadists as lions and warriors), employing hyperbole when mentioning contemporary jihadist acts, eulogizing martyrs and mythologizing their virtues. Constructing a coherent enemy “other” helps to produce a sense of identity and common global cause for jihadist struggles that may in fact be fuelled in large part by local and regional concerns.’

Much of this rings true, even in the case of poets sprouting Hindutva poetry, like Kamal.

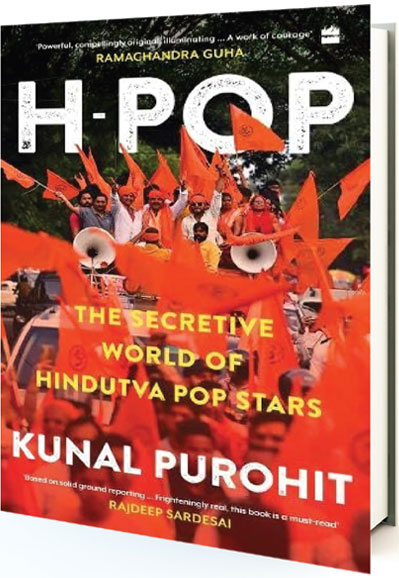

H-POP: THE SECRETIVE WORLD OF HINDUTVA POP STARS

Kunal Purohit

HarperCollins, Pg 283, Rs 499