Fumbling on national security while being sure-footed on the economy. An extract

On 24 December 1999 Indian Airlines IC 814 from Kathmandu to Delhi was hijacked by a Kashmir-based terrorist group. The pilot was first ordered to fly to Lahore, and when Lahore refused it permission to land, IC 814 touched down in Amritsar at 7 p.m., with only 20 minutes of fuel remaining. The plane was hijacked a little after 4.30 pm., but an emergency cabinet meeting in Delhi got under way at Vajpayee’s residence only at 6 p.m. Vajpayee was away in Lucknow at the time of the hijacking. He was not immediately informed of the seizure of the plane as he was en route to Delhi and was able to join the emergency meeting only at 7 p.m., more than two hours after the plane was captured. It was the end of December. The new year would herald a new century and Vajpayee had been looking forward to his seventy-fifth birthday and the party planned for him in Chennai by Pramod Mahajan. IC 814 crashed into his year-end reverie and he was unable to gather his wits in time.

On 24 December 1999 Indian Airlines IC 814 from Kathmandu to Delhi was hijacked by a Kashmir-based terrorist group. The pilot was first ordered to fly to Lahore, and when Lahore refused it permission to land, IC 814 touched down in Amritsar at 7 p.m., with only 20 minutes of fuel remaining. The plane was hijacked a little after 4.30 pm., but an emergency cabinet meeting in Delhi got under way at Vajpayee’s residence only at 6 p.m. Vajpayee was away in Lucknow at the time of the hijacking. He was not immediately informed of the seizure of the plane as he was en route to Delhi and was able to join the emergency meeting only at 7 p.m., more than two hours after the plane was captured. It was the end of December. The new year would herald a new century and Vajpayee had been looking forward to his seventy-fifth birthday and the party planned for him in Chennai by Pramod Mahajan. IC 814 crashed into his year-end reverie and he was unable to gather his wits in time.

As news of the hijacking spread, wailing relatives of IC 814 passengers gathered in front of the prime minister’s residence at 7 Race Course Road. TV news went into overdrive, broadcasting their anxious laments round the clock. When IC 814 was on the ground in Amritsar, the government’s Crisis Management Group (CMG) and Cabinet Committee on Security erupted into the Tower of Babel. Views and counterviews kept being interchanged. At one point, foreign minister Jaswant Singh snatched the phone, telephoned the Punjab police chief and ordered that the plane be immobilized on the runway by means of a trolley or a truck. But the Punjab police did nothing as the Punjab chief minister kept insisting that passengers should not be harmed. Vajpayee sat listening in silence, taking no decisions, only occasionally and plaintively asking about the passengers’ plight. A chattering, arguing Vajpayee government and a silent, indecisive and passive prime minister failed to take the initiative to immobilize IC 814 all the while—almost 50 minutes—it stood in Amritsar. The hapless plane, unable to refuel due to airport missteps, again took off for Lahore, where it landed and refuelled, then landed at a military airbase near Dubai at around one-thirty the next morning. At Dubai, India reportedly readied a commando-style operation but the local authorities didn’t cooperate and again India failed to take any decisive action. The hijackers had stabbed and killed a passenger, twenty-five-year-old Rupin Katyal, and in Dubai his body was flung out of the plane in a chute. In Dubai twenty-seven passengers—women and children and some injured—were released. Someone from the government was needed to bring the twenty-seven back from Dubai. Civil aviation minister Sharad Yadav immediately volunteered but confessed he had no passport. The demands of alliance politics had led Vajpayee to appoint as civil aviation minister a rustic political warhorse who had never flown on an international flight. A passport was hastily arranged for Sharad Yadav—the visit becoming his first overseas trip—who received the released hostages in Dubai. Meanwhile the grief-crazed relatives kept up their 24×7 hysteria on TV and high-decibel pressure kept building on the government, which Vajpayee couldn’t withstand. A shamefaced India meekly gave in to the terrorists demands and released three wanted terrorists being held in jails in Delhi, Jammu and Srinagar. Taking off from Dubai at 6.20 a.m. on 25 December, IC 814 now flew to an undisclosed location, landing in Taliban-controlled Kandahar at 8.30 a.m. to remain on the tarmac for six days while the Vajpayee government and hijackers negotiated. Jaswant Singh staked his own credibility and offered to fly with the released terrorists to Kandahar. After Jaswant Singh’s plane had taken off, Vajpayee whispered in a weak and exhausted voice, ‘Kya woh chale gaye? [Has he gone?] the phrase encapsulating the prime minister’s plight as a helpless bystander through the entire sordid saga. After Jaswant Singh had delivered the terrorists to the Taliban, the remaining hostages were freed and returned to India on the evening of 31 December, after six days of torment. The sight of a union minister of the apparently strongly ‘nationalist’ India, which had only that year declared victory in the Kargil war, escorting terrorists to their freedom was a shameful disgrace.

The IC 814 hijacking episode had been a fiasco, and all the top officials in the Vajpayee government, from Brajesh Mishra to A.S. Dulat to the director of the National Security Guard (NSG), Nikhil Kumar, came in for scathing criticism. Cabinet Secretary Prabhat Kumar ‘took his time calling the CMG’; Brajesh Mishra ‘sent confused signals’; Dulat ‘should have pre-empted the hijack’, and Nikhil Kumar ‘could have ensured the NSG reached on time’, said media reports. Vajpayee became a victim of his own consensual style: the taking-everyone-along, delegating, hands-off approach meant government became paralysed by a cacophony of decision makers. The ‘friendly, happy government headed by the easy-going prime minister’ had failed abysmally at a time when swift hard decisions needed to be taken.

Operation Parakram in 2001-02 too was dubbed a strategic fiasco. The operation began as a result of events that took place on 13 December 2001. That morning the Vajpayee government faced a volley of attacks from the Opposition in Parliament. ‘Coffingate’ or an alleged scam in the purchase of coffins from a US-based company during the Kargil war to transport soldiers’ bodies, rocked both Houses. Kafan chor, gaddi chhor [Coffin thief, leave the throne] shrieked Opposition members rather tastelessly, creating such a ruckus that both Houses were adjourned. Around 11.40 a.m. a while Ambassador car came speeding into Parliament. Five heavily armed men leapt out, shouting ‘Pakistan Paindabad [Long live Pakistan] as they sprayed bullets and lobbed grenades. Nine security staff were killed and the gunmen—suspected Pakistan-based terrorists—all died. Outrage rippled across the country that India’s Parliament itself should be targeted, and the Vajpayee government mobilized for war with Pakistan. By January 2002 masses of Indian troops stood along the India-Pakistan border. Operation Parakram had begun. Parakram was yet another example of the Vajpayee government’s running theme of fumbling on national security while being sure-footed on the economy.

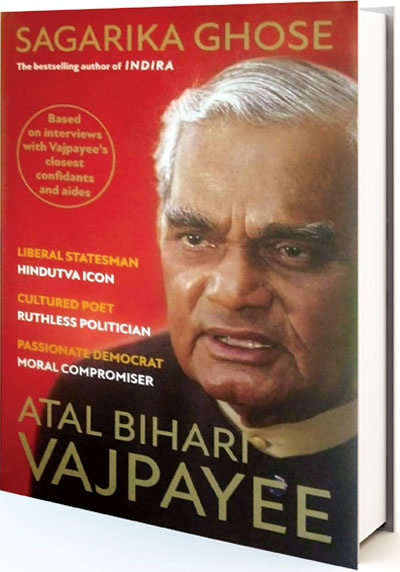

ATAL BIHARI VAJPAYEE: INDIA’S MOST LOVED PRIME MINISTER

Sagarika Ghose

Juggernaut, Rs 799, Pg 395