How the Kashmir issue provided a leg up to Vajpayee’s political career. An extract

Abhishek Choudhary

Mookerji’s first impulse was to agitate on traditional social and economic issues of the day—beginning with food inflation, especially the increase in the prices of rationed wheat. But by the time the Jan Sangh recovered from the shock of defeat, the issue had been hijacked by the communists and socialists, who had fared better at the polls. Low on morale, the party had, its president lamented in mid-May, kept itself ‘aloof as a mere spectator’. The RSS launched a massive signature campaign with the intention to force the government to bring a central legislation to ban the killing of cows. Mookerji sympathized with it from a distance, but did not think it a strong enough plank to start a countrywide agitation. Unable to come up with any new ideas, the party fell back on an old obsession: Kashmir.

Mookerji’s first impulse was to agitate on traditional social and economic issues of the day—beginning with food inflation, especially the increase in the prices of rationed wheat. But by the time the Jan Sangh recovered from the shock of defeat, the issue had been hijacked by the communists and socialists, who had fared better at the polls. Low on morale, the party had, its president lamented in mid-May, kept itself ‘aloof as a mere spectator’. The RSS launched a massive signature campaign with the intention to force the government to bring a central legislation to ban the killing of cows. Mookerji sympathized with it from a distance, but did not think it a strong enough plank to start a countrywide agitation. Unable to come up with any new ideas, the party fell back on an old obsession: Kashmir.

Jammu & Kashmir was the only Muslim-majority state of India that was, under Sheikh Abullah’s leadership, determined to remain autonomous. Given their hostile relationship in the past, Abdullah, the new prime minister of J&K, was keen to pay the former ruling class of Dogras back in their own coin. Soon after taking over he had, in July 1950, carried out radical land reforms without paying any compensation, which had hurt many of the Dogra jagirdars. In theory the Jan Sangh supported land reforms, with Mookerji mentioning in his presidential speech of October 1951 that the ‘abolition of zamindari along with other integrated measures will usher in agricultural reforms necessary for the country. But compensation should be paid.’ Since the party drew much of its support form the landed class and some lapsed maharajas, its private stand was more ambiguous.

The Dogras resented the decline in their economic and political influence. It did not help that officials sent by Abdullah to run the administration in Jammu ‘did not conduct themselves well’ either. Unfortunately, for someone who had spent years in the prison, Abdullah acquired a reputation for becoming ‘notoriously intolerant of dissent’, frequently locking up opposition workers without trial, sometimes for year.

Matters worsened during the 1951 assembly elections. The nominations for forty-five out of forty-nine Praja Parishad candidate were declared invalid on flimsy grounds. The Parishad boycotted the election; the National Conference had a walkover on all of its seventy-five seats. With no space for manoeuvre, the Praja Parishad began to agitate for removing the special status granted to J&K and to fully merge the state, same as the other 600-plus monarchies, with India. The Parishad’s most popular slogan was ‘Ek Vidhan, Ek Nishan, Ek Pradhan’—one constitution, one flag, one premier—for all of India. If a full merger was not possible, the Praja Parishad demanded that Jammu should be separated from Kashmir and merged with Punjab or Himachal Pradesh.

The Jan Sangh saw the Parishad’s campaign as a natural cause to attach itself to: the party in Delhi decided to celebrate the last week of June 1952 as ‘Kashmir Week’. On 26 June, addressing a crowd of 1,500 people at Gandhi Grounds, ‘Attal Behari Bajpai emphasized that they would not hesitate to lay down their lives, if need be, for the integration of Kashmir with India.’ He also argued that ‘if hereditary rulership was to be terminated in Kashmir, it should also be terminated in Hyderabad’.

The crisis simmered for a while, with the Jan Sangh’s attention shifting to the refugee crisis in East Pakistan. The Praja Parishad was irked that under the special status granted to J&K by Article 370, Abdullah had the freedom to make his own laws (on most matters except defence and foreign affairs) and fly a separate flag (which was the National Conference flag with minor alteration). When the J&K government flew it over Jammu secretariat on 17 November, the Praja Parishad gave a call for a do-or-die agitation. The J&K government cracked down on the protestors, arresting the elderly president Prem Nath Dogra and others. Being a sister organization, the Jan Sangh was asked to help make the agitation popular across county. As the Jan Sangh geared up for its annual session to be held in Kanpur during 29-31 December, the party also finalized the logistics of the ‘mass movement in which leaders and volunteers would proceed to Kashmir to help the Praja Parishad agitation’.

At Kanpur, the party formally passed a resolution supporting the Jammu satyagraha for the integration of J&K with the rest of India. The overexcited younger delegates of the party, the majority of them from the RSS, egged Mookerji on to challenge Nehru to ‘face the Jan Sangh Satyagraha in the rest of India as well’. The president counselled patience, saying he would first discuss the matter with the prime ministers. Back in Delhi, Mookerji began a protracted correspondence with Nehru and Abdullah, urging the latter to open dialogue with the Praja Parishad leadership and come up with a compromise.

This did not go anywhere. Nehru knew that the Praja Parishad derived all its energy from the RSS and the maharaja, and he detested both. Therefore he did not ask Abdullah to hear out the Dogras, even though by early 1953 it was no longer only jagirdars venting their frustration at Abdullah’s socialist government: the movement was becoming popular among the Hindus of Jammu region, and some of their grievances were genuine. The prime minister was livid with the Parishad and the Jan Sangh because the agitation had weakened India’s position in the UN, and would further complicate any compromise with Pakistan. Worse, it was making the Muslims of J&K suspicious of a shared future with India. In his replies to Mookerji in February 1953, Nehru emphasized that for any talks to take place the Praja Parishad had to first ‘stop the agitation completely and then deal with any grievances’. A confrontation was unavoidable.

The Jan Sangh’s decision to plunge itself wholeheartedly into the Jammu satyagraha gave Atal’s life another swift, unexpected turn. Sometime in January-February 1953, he was appointed Mookerji’s private secretary. This was partly because other bright young men in the RSS-Jan Sangh had already been assigned important taskes: Deendayal, the general secretary of the UP Jan Sangh was promoted at Kanpur to the post of National General Secretary of the party. The UP charge was handed over to Nanaji who had, among other things, successfully organized the Kanpur annual session. Atal was not yet a member of the Jan Sangh’s working committee…

Atal’s first assignment was to travel alone in the Hindi heartland to popularize the Jammu satyagraha among the masses. In the past year, he had come to have more than just an acquaintance with the Jan Sangh president. Atal had travelled with Mookerji in early August 1952 to Jammu and ‘discovered his simplicity and ease of manners’.

Atal travelled widely in UP: ‘On 26 March, Sri Vajpayee, the private secretary of Dr Syama Prasad Mookerji… began his tour of eastern Uttar Pradesh to popularize the movement,’ reported Panchjanya. Constantly on the move, over the next two weeks he covered more than a dozen districts. Everywhere he informed and incited his audience: ‘Isn’t it surprising that even the well educated people in eastern UP are unaware that Sheikh Abdullah has stitched a separate flag for himself?’

‘It doesn’t take much time to reach Jammu-via train till Pathankot, and from there by road. And if you have just about enough money for the fare, you can board a train in Delhi at night and by next afternoon you will reach Jammu soaking in the beautiful views of snow-capped mountains. But far more important than train or bus or the money to reach there is something else—a permit… If you don’t possess this permit, those great inventions like railways and cars, and the currency in your pocket minted dutifully by the government, have no worth.

After addressing a crowd in Ballia, he overheard some khadi-wearing Congressmen whispering among themselves that the talk of ‘two constitutions, two prime ministers, two symbols’ in J&K was untrue, and that the Jan Sangh was in the business of ‘spreading canards’. Everywhere Atal insisted that it was a democratic movement: ‘Leaders of the Parishad and Jan Sangh understand rather well that the rajas and maharajas are a thing of the past. This is janyug—the age of masses, which has no place for monarchy and dynasties.’ This was an insincere, if not entirely false, claim.

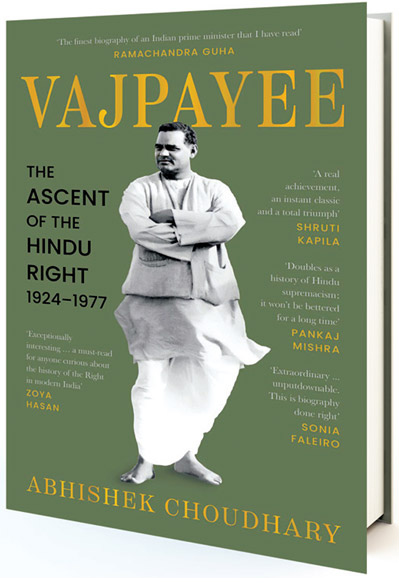

VAJPAYEE: THE ASCENT OF THE HINDU RIGHT, 1924–1977

Abhishek Choudhary

Picador India, Pg 400, Rs 899