How India’s rise is hemmed in by systemic and infrastructural fault lines. An extract

Japan-India investment promotion partnership

Japan-India investment promotion partnership

During PM Modi’s visit to Japan in September 2014, PM Abe and PM Modi signed a joint declaration in which Yen 3.5 trillion of fresh public and private investment and financing from Japan in five years was promised. The Indian side agreed to improve the investment environment in India to facilitate investment by Japan by promoting a ‘Special Package for Japanese Investment’. Its objective was to promote investment by Japanese companies in India.

There are, however, certain difficulties in the investment climate in India.

The foremost is power scarcity. For some regions (such as Gujarat and the vicinity of Chennai), foreign companies by and large face power shortages. Power breakdown and voltage fluctuations are a daily affair. In addition to power generation shortage, the foremost reasons are shoddy power grids where there is loss of power during transmission and power theft as factories and households steal electricity. Foreign companies are obliged to install captive power generation facilities in their factories to deal with power breakdowns. This is obviously unwanted extra investment. Most of the households have given up on getting uninterrupted power, while the affluent class and foreigners install power gensets in their homes.

Indian roads are also of poor quality. Expressways in the real sense of the term are very few in number such as the Delhi-Agra Expressway, Mumbai-Pune Expressway, and the Bandra-Worli Sea Link in Mumbai.

National highways are, on the whole, in poor shape. In addition to cars and trucks, one can find even bullock carts and carts pulled by camels on the same roads. Thus, these roads are extremely dangerous and accident prone.

When the author was staying in India, one of the Japanese companies making sheet glass with its factory in Gurugram complained that many of the glass shipments break on NH 8 during transportation. Maruti Suzuki that has factories in Gurugram and Manesar is also apprehensive about safe transport when it sends its cars on trucks. The DMIC (Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor) will be a solution to this problem.

Drinking water and sewage systems are also a problem in India. Drinking water cannot be consumed without boiling and sterilization. Yet heavy metals cannot be isolated. In India, the majority of areas have no drinking water supply. Securing industrial water is also a source of headache. Access to water is a struggle for both companies as well as individuals.

In rural areas, as ground water is drawn excessively for agriculture, there is the intrusion of salty water. When the water evaporates, the ground covered with salt hampers cultivation. India has inadequate energy resources but the water shortage is really acute.

India’s sewage system is also poor. The Yamuna, a tributary of the Ganges, that flows through Delhi, is a holy river, but if one goes close, one finds sewage effluents and all kinds of objects floating in the river. There is a stretch on the banks of the Yamuna which is home to elephant keepers who rent out elephants for weddings and events. However, it is really pitiable for the elephants as they bathe in that polluted river water. Japan participates in the Yamuna clean-up project and has installed several filtration facilities, and yet their number is inadequate compared to the demand.

***

Japan-India cooperation in East Asia

There are several regional groupings in Asia. East Asia has the East Asia Summit (EAS). The ASEAN summit centred on ASEAN countries (a ten-member grouping consisting of Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar). There are summit talks between ASEAN member states and countries from outside the region such as Japan, the US, Canada, China, Australia, and India. Japan and India have a broad agreement within the framework of these summits on cooperation to enhance ocean security, fight against terrorism and violent extremism, help cope with climate change and intra-region connectivity (transport and communication networks).

Both India and Japan are concerned about the security situation in Asia. Both have criticized North Korea’s nuclear and ballistic missile development activities in the strongest manner and are demanding that North Korea comply with all its international obligation, including the UNSC resolutions and immediately initiate measures towards the denuclearization of the Korean peninsula.

Even with regard to the South China Sea, where some the Asian nations, including China, make contending claims, both India and Japan have adopted a principled stance that premised on the need to resolve disputes by peaceful means based on the principles of international law, including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Both countries want to check and restrain China, which not only has laid claims to the islands in the South China Sea almost in their entirety but also occupies and territorializes them, resorting even to the threat of the use of force.

On the economic front, both Japan and India participated in the East Asia Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) negotiations. The negotiations started among fifteen countries; ten ASEAN members, Japan, China, Republic of Korea, Australia, New Zealand, and India. Japan and India cooperated with each other and aspired to achieve a ‘modern, comprehensive, high quality, and mutually beneficial’ agreement. However, India insisted at the last moment to include a clause for freer movement of labour and a less ambitious agreement on tariffs. The other partners objected. In order to prevent China’s influence from becoming overwhelming, Japan tried to persuade India to be accommodating, but in vain. Finally, the rest of the negotiating partners decided to conclude the negotiations without India, and signed the protocol on 15 November. Japan continues to hope that one day India will come back to the RCEP.

On the other hand, twelve countries of the Asia-Pacific region, including Japan and the US, signed the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) Agreement in February 2016 that is broad-based and has greater degree of liberalization not only in the trade of goods, but trade in services, investment, and intellectual property rights.

However, in January 2017, former US President Donald Trump shocked the world by announcing his unilateral decision for the withdrawal of the US from the TPP. The rest of the participants finally abandoned hopes of enacting the original agreement of TPP12 under the Trump administration and opted for a eleven membership TPP (TPP11). Eleven countries agreed to enact TPP11 while leaving the possibility for the eventual participation of the US at a later stage. In December 2018, Mexico, Japan, Singapore, New Zealand, Canada, and Australia enacted TPP11 by ratifying it. In January 2019, Vietnam ratified TPP11 and joined the group. The rest of the signatory countries, Brunei, Malaysia, Peru, and Chile will eventually ratify the agreement. In Japan, TPP11 came into effect from January 2020.

Joe Biden, during his presidential campaign, declared that the US would join TPP11 sometime after his administration commences in January 2021.

China is not a part of the TPP. The TPP is the most advanced comprehensive economic partnership agreement; China cannot fulfil all the conditions of TPP for several reasons such as protection of intellectual property rights (IPR), liberalization of advanced trade, and investment. The TPP is an agreement that can become a model for the whole world to emulate. It is much more advanced than the RCEP. China is happy that the US withdrew from the TPP and is now trying to take the lead in the RCEP.

Recently China started to show its interest in TPP, maybe to fill the vacuum left by US and to pretend to champion free trade. The US is expected by TPP members, in particular Japan, to come back at the earliest under the Biden administration. The TPP will continue to be a difficult proposition for it so long as India continues to stick to its rigid stance as shown in the RCEP negotiations.

| Japan–India | Japan–China | Ratio | |

| No. of Japanese visitors | About 210,000 | About 2.5 million | 1/12 |

| No. of tourists to Japan | About 103,000 | About 2.5 million | 1/48 |

| No. of foreign students in Japan | 1,102 | 108,331 | 1/98 |

| No. of Japanese residents | 8,655 | 131,161 | 1/15 |

| No. of registered residents in Japan | 28,047 | 785,982 | 1/28 |

| No. of Japanese language students | About 20,000 | About 1.05 million | 1/52 |

| Exchange between local governments | 13 | 362 | 1/28 |

| No. of flights | 28/week | 690/week | 1/25 |

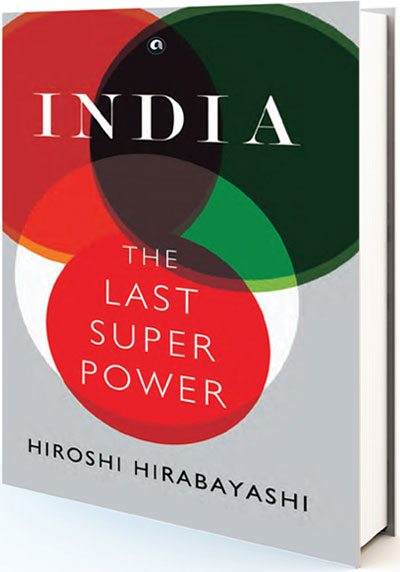

INDIA: THE LAST SUPER POWER

Hiroshi Hirabayashi

Aleph Book Company, Pg 224, Rs 580