How India’s relations with its eastern neighbour continues to flummox policymaking. An extract

When China’s President Xi Jinping visited India on 17-19 September 2014, Modi, bypassing diplomatic protocols, received him at Ahmedabad in his home state, Gujarat, where they visited the Gandhi Ashram, promenaded on the Sabarmati riverfront and in the Gujarati tradition of welcoming guests, they sat side-by-side on a swing (jhoola). In Delhi, President Xi offered to invest $20 billion in India’s infrastructure for the next five years, part of a slate of 12 agreements that both sides signed during the visit. Curiously enough, when they were building rapport and bonding with each other in Ahmedabad, the Chinese troops were sneaking into Ladakh to build a road that led to a confrontation, and after a five-day standoff, the Chinese troops retreated form Ladakh. What China said was different from what China might do, it seemed.

When China’s President Xi Jinping visited India on 17-19 September 2014, Modi, bypassing diplomatic protocols, received him at Ahmedabad in his home state, Gujarat, where they visited the Gandhi Ashram, promenaded on the Sabarmati riverfront and in the Gujarati tradition of welcoming guests, they sat side-by-side on a swing (jhoola). In Delhi, President Xi offered to invest $20 billion in India’s infrastructure for the next five years, part of a slate of 12 agreements that both sides signed during the visit. Curiously enough, when they were building rapport and bonding with each other in Ahmedabad, the Chinese troops were sneaking into Ladakh to build a road that led to a confrontation, and after a five-day standoff, the Chinese troops retreated form Ladakh. What China said was different from what China might do, it seemed.

China’s frequent transgressions into India across the 2,520-mile-long Himalayan border (411 incursions in 2013, for example) normally go unreported in the media; but when the Chinese troops tried road building in the Indian territory as happened in Ladakh during President’s Xi visit, it could not be ignored. According to a South Asian expert, this wasn’t ‘the first example of incursions preceding major bilateral meetings. Last year (2013), a significant mid-April incursion led to Chinese troops setting up camp in tents, also in the Ladakh area (Depsang). This extended over a two-week period into early May, and Indian media reported that the Chinese troops had extended nineteen kilometers into Indian territory. Premier Li Keqiang visited Delhi May 19 to 21 of last year (2013).’

Reciprocating the visit to Modi’s home state, President Xi hosted Prime Minister Modi in his home town Xian, 14-15 May 2015, where they talked and walked like friends discussing matters of mutual concerns including the boundary dispute and terrorism and establishing confidence-building measures. But underneath the bonhomie, there was tension. Less than a month before Modi’s visit, Xi had paid a highly acclaimed visit to Pakistan, its all-weather friend, where he signed an agreement to invest $46 billion for projects under the CPEC that would pass through Kashmir (Pakistan occupied territory). But during the G20 summit in Hangzhou, China, on 4 September 2016, when Modi told Xi ‘to ensure durable ties and their steady development, it is of paramount importance that we respect each other’s aspirations, concerns and strategic interests,’ the Indian concerns were ignored.

Again, when during a meeting on the sidelines of the BRICS and Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summits in Ufa, Russia, Modi raised serious issues about China blocking US Security Council action against Pakistan for setting free the 26/11 Mumbai terror attack’s mastermind Zaki-ur-Rehman Lakhvi, Xi was not persuaded. Nor did China agree to support India’s membership in the NSG that controlled access to sensitive nuclear technology in spite of the India-United States Nuclear Agreement. China refused to accept India as a legitimate nuclear-weapons power state as the rest of the world had done. Apart from blocking India’s entry to NSG, China vetoed the UN Security Council proposal to ban Pakistan’s terrorist organization Jaish-e-Mohammed and its leader Masood Azhar. Similar fruitless exchanges continued in 2017 between the two leaders on the sidelines of the summits at BRICS, Goa, India, SCO, Astana, Kazakhstan and G20, Hamburg Germany.

India not only strongly protested against the CPEC passing through its sovereign Kashmir territory but much to China’s chagrin, India also declined the invitation to join its Belt and Road Initiative summit held in Beijing, 14-15 May 2017. India also found that China had begun to make creeping advances in its Himalayan backyard, which led to the eruption of hostilities at Doklam, a crucial strategic plateau located between Bhutan’s Ha Valley to the east, India’s Sikkim state to the west and Tibet’s Chumbi Valley to the north. India discovered that the Chinese army had begun to extend an existing road from Chumbi Valley into Doklam, the region that is part of Bhutan but claimed by China. On 18 June 2017, India, under the aegis of the Bhutan-India Friendship Treaty (2007), moved its troops form Sikkim into Doklam to stop the Chinese troops form constructing the road. The road would have threatened India’s strategic Siliguri Corridor, the so-called Chicken Neck, a narrow 17-mile-wide stretch of land located in West Bengal, between Nepal and Bangladesh, that connects India’s entire northeast region with the rest of India. Much was at stake because Siliguri city is the strategic nodule that links Bhutan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sikkim, Darjeeling Hills and Northeast India, including Arunachal Pradesh, upon which China has laid fictitious claims. The Chinese control of the Doklam plateau would have made the entire region defenceless. After a long military and diplomatic standoff, India and China withdrew their troops from Doklam on 28 August 2017 without however reaching a conclusive resolution to the dispute, although both countries promised to find fresh modes of engagement and instructed their border forces to build trust and understanding in order to maintain the peace at the borders.

When the two leaders met for a one-to-one informal summit in Wuhan, China, 26-28 April 2018, to reassess their strategic positions and strengthen bilateral trade relations, there was a palpable taw between the two leaders, though Doklam, China’s resistance to Indian membership of the Nuclear Supplier Group and China’s puzzling ambivalence about Pakistan’s terrorist organization Jaish-e-Mohammed had not been forgotten.

India-China experts at Brookings observed that the changing international situation, especially China’s deteriorating trade relations with the US and ‘the unpredictability of the U.S. administration have made the Chinese leadership nervous… With the U.S. following a more confrontational policy, China has been making outreach efforts to countries in its periphery… An attempt to thaw relations with India should also be seen in this context… (Nonetheless) assessments of Chinese behaviour… will be a challenge for India over the next year…’

China’s two-track relations, on the one hand growing trade and commerce relations and on the other hand frequent transgressions on the Himalayan border along with denial of support for the NSG membership and the inexplicable reluctance to denounce Pakistan-based terrorist groups, were the biggest challenges for Modi in his first term. The resilience and strength of India have always existed in its unfathomable capacity to live and thrive amidst confusion, doubts and uncertainties. Not only China but the United States too would be continuously challenging India.

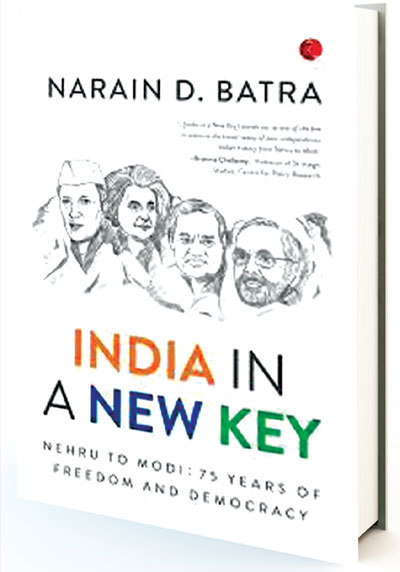

INDIA IN A NEW KEY

NEHRU TO MODI: 75 YEARS OF FREEDOM AND DEMOCRACY

Narain D. Batra

Rupa, 569, Rs 995