How through sheer determination, the author proved that loss of limb does not mean loss of abilities. An extract

Maj. Gen. Ian Cardozo (retd)

Being invalided out seemed like a dismal option considering that I knew, in my heart, that even with an artificial leg I could be nearly as good as I was before I got injured. I had read Reach for the Sky, the story of Douglas Bader, an RAF pilot. He had lost both legs and continued to fly Spitfires during the Second World War. He had become an air ace by shooting down 21 German fighter-aircraft. If he could do it, why couldn’t I face my challenges in the same way?

Being invalided out seemed like a dismal option considering that I knew, in my heart, that even with an artificial leg I could be nearly as good as I was before I got injured. I had read Reach for the Sky, the story of Douglas Bader, an RAF pilot. He had lost both legs and continued to fly Spitfires during the Second World War. He had become an air ace by shooting down 21 German fighter-aircraft. If he could do it, why couldn’t I face my challenges in the same way?

***

At the hospital we could not get measured for our artificial legs until our stumps healed. It took approximately four months for that to happen. During this time, we were all over Pune on our crutches and our bandaged stumps—at the bar of the Southern Command Officer’s Mess, at the races, at the movies, at Poona Coffee House on East Street and at the restaurants on Main Street (now called MG Road). The citizens of Pune had become used to us and accepted us as their own.

All the activities that we were indulging in required money and regrettably we lived beyond our means by drawing cash from a money lender and spending it recklessly. His shop was on an offshoot of Main Street and he allowed us to use postdated cheques and charged us exorbitant rates of interest. Looking back, I think we lived as if there was no tomorrow because we did not know what ‘tomorrow’ held for us.

Around this time, Headquarter Southern Command decided to organize a reception for the battle casualties lodged at the Pune and Kirkee military hospitals. The Army Commander was the host and so I decided to speak to him. The Army Commander was from the Gorkhas and Colonel McKean, a senior staff officer from Headquarter Southern Command was from Darjeeling. Both spoke Nepali. So, I went and spoke to Colonel McKean in Nepali and asked him whether I could meet the Army Commander. ‘Sure,’ he said and asked me why I wanted to meet him. I told him that we battle casualties were in the dark about our future and that we wanted to know whether we could go back to our battalions. Speaking in Nepali, he introduced me to the Army Commander. I was on my crutches.

The Army Commander was speaking to some senior officers. He excused himself and turned around to meet me and after being introduced, he said:

‘So, are you from the RIMC?’

‘No sir.’ I said slightly taken aback.

‘Then are you from the 11th Gorkhas?’

‘No sir.’ I said, even more mystified.

Colonel McKean explained the reason why I wanted to speak with him.

The Army Commander turned to me and said, ‘That is for the doctors to decide.’

I answered, ‘Sir, how can the doctors decide what I can or cannot do? It is for the chief and the army commanders to decide how battle casualties can best be employed.’

The Army Commander was more than annoyed. He said, ‘It is not for you to decide what the chief and the army commanders should do. As far as I am concerned, army doctors will decide what your medical category will be and that will decide how you can best be employed. Is that all?’

The Army Commander’s attitude was discouraging. It appeared that the mindset of the military hierarchy was biased against battle casualties, and that would exclude us from the command of troops.

I was disappointed. The chief and the army commanders were our last resort and it appeared that the Southern Army Commander, at least, was not inclined to support our claim that we should be permitted to join our units and that at the very least, we should be given an opportunity to prove our credentials one way or another.

By then, it was almost four months and our stumps had healed. Now began the serious business of being measured for our artificial legs, trying out our prosthesis till we got a perfect fit. This involved a lot of hard work that started at 8.30 in the morning and lasted until 4.30 p.m. with only a break for lunch in between. Much depended on the shape and health of our stumps—the healthier the stump, quicker we could begin to walk.

The aim was that we should be able to walk normally; that our gait should be so seamless that no one should be able to guess that we had an artificial leg. For below knee amputees like myself, it was easier to walk naturally. However, for above knee amputees like Abu Tahir and Yeshwant Rawat, an officer from my battalion, it was more difficult to conceal a pronounced limp.

Major Abu Tahir was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel by Bangladesh while he was still with us at the Artificial Limb Centre. A month later he was promoted to Colonel’s rank. Suddenly, he had became senior to us, rank wise.

I was posted to Military Secretary’s (MS) Branch, Army Headquarters, New Delhi. During my interview with the MS I was told that Gen Manekshaw had specifically asked that I be posted to MS Branch to be part of a committee to evolve a policy for battle casualties.

Maybe General Manekshaw saw from my record that I was from his regiment and that was probably why he directed that I be part of this committee.

It was around this time that we first heard the term ‘post traumatic disorder’—that some battle casualties could not accept the horrors of war to which they had been subject or the events which led to their disability and this adversely affected their emotional make-up. None of us at the Artificial Limb Centre appeared to be affected in this way. There were so many of us who were amputees and we became a strong support to each other. However, a Major from the artillery, who had lost both his legs above the knee took it badly. He had been fitted with two wooden block-like legs that reduced his height considerably which made him look like a dwarf. It was difficult for him to walk and he had to waddle around—that too with a stick. We heard later that he shot himself. Was this a part of post-traumatic disorder? We did not know, but it felt terrible to learn that a disabled soldier had ended his life.

The Major was senior to most of us and while there were lots of us single-leg amputees who had each other for company and were able to move around Pune on our crutches, he was alone and lonely in his room. We sometimes went to his room to keep him company but he probably sensed that this was more an act of charity rather than our desire for his company. We discovered that he was not married but there was a girl somewhere in his life that he had been fond of, but things had come to an end before he lost his legs, and now there was no question of being able to pick up the threads of a lost relationship. When we talked about the war, he often said that he wished that he had been killed rather than forced to live his present existence.

Later on, when I heard that he had killed himself, I felt a sense of remorse, perhaps even guilt. Would this have happened if I and others like me, had spent more time with him and given him the companionship that he must have longed for? Was this what post-traumatic disorder was all about? It’s something most of us knew very little about—mental health issues that affect soldiers due to the violence of war had not been examined in depth until that time i.e., what needed to be done to alleviate the pain that some soldiers suffer; with no one to understand what they are going through. Many soldiers had died in the war but there was nothing more tragic than for a soldier to take his own life because there was no one to empathize with his plight.

Later on, when I heard that he had killed himself, I felt a sense of remorse, perhaps even guilt. Would this have happened if I and others like me, had spent more time with him and given him the companionship that he must have longed for? Was this what post-traumatic disorder was all about? It’s something most of us knew very little about—mental health issues that affect soldiers due to the violence of war had not been examined in depth until that time i.e., what needed to be done to alleviate the pain that some soldiers suffer; with no one to understand what they are going through. Many soldiers had died in the war but there was nothing more tragic than for a soldier to take his own life because there was no one to empathize with his plight.

‘Sam Bahadur’ cared for his officers and soldiers. He reminded MS Branch and AG’s Branch that personnel of the Indian Army needed to know that if they were wounded their interests would be taken care of. He had remarked that if such conditions were not created, who would stick their necks out in a future war? Having himself been badly wounded in the Second World War at the Battle of the Sittang River in Burma in 1942, he understood what it was like to be wounded. This is something the present and future military and political hierarchy need to think about!

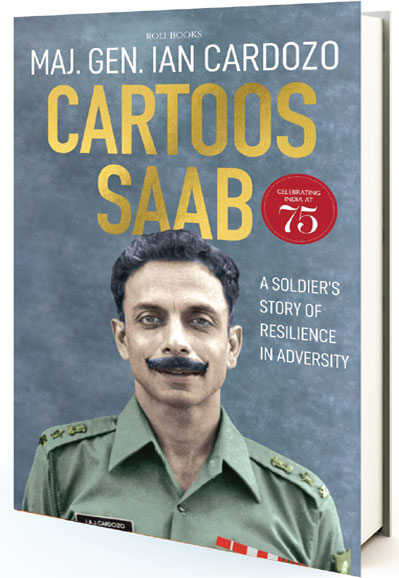

CARTOOS SAAB: A SOLDIER’S STORY OF RESILIENCE IN ADVERSITY

Maj. Gen. Ian Cardozo

Roli Books, Pg 456, Rs 795