Why South Asian borders induce distress and dislocation instead of security. An extract

Nagaland remains one of India’s most highly policed states, and the army maintains a permanent presence and surveillance to control all local factions. Votes work on the barter system and remain the most valuable currency. Despite the value of votes, the rule of law has very little currency. Travelling through Nagaland, I found myself in the midst of the two ‘parallel governments’ oppressing their people in perfect coordination and complicity: the National Socialist Council of Nagaland’s (NSCN-IM) Isak-Muivah faction has a Naga Army and there is the Indian Reserve Battalion. The NSCN—a modern Naga separatist group—was formed on 31 January 1980 to oppose the Shillong Accord of 1975, signed as a peace agreement between the previous separatist group, the NNC, and the Indian government. Drug trafficking from Myanmar is reported to be a major source of income for the NSCN-IM, and I heard many stories of extortion and smuggling in regions where the group carries influence. Illegal taxation is rampant. Petty crimes are policed by communities, which take the law into their hands. This is what Indian has to show for itself after seventy years of rule and presence in the region.

Nagaland remains one of India’s most highly policed states, and the army maintains a permanent presence and surveillance to control all local factions. Votes work on the barter system and remain the most valuable currency. Despite the value of votes, the rule of law has very little currency. Travelling through Nagaland, I found myself in the midst of the two ‘parallel governments’ oppressing their people in perfect coordination and complicity: the National Socialist Council of Nagaland’s (NSCN-IM) Isak-Muivah faction has a Naga Army and there is the Indian Reserve Battalion. The NSCN—a modern Naga separatist group—was formed on 31 January 1980 to oppose the Shillong Accord of 1975, signed as a peace agreement between the previous separatist group, the NNC, and the Indian government. Drug trafficking from Myanmar is reported to be a major source of income for the NSCN-IM, and I heard many stories of extortion and smuggling in regions where the group carries influence. Illegal taxation is rampant. Petty crimes are policed by communities, which take the law into their hands. This is what Indian has to show for itself after seventy years of rule and presence in the region.

The Naga city of Tuensang, difficult to access and situated right on the border with Myanmar, is where the Naga government was first established in 1954. The people of Tuensang continue to find themselves in the crossfire of three opposing and fighting groups—the Indian Army, the Naga underground and the Burmese armed forces. During the height of the insurgency, the Indian Army came in search of Naga underground fighters. The Burmese Army also made incursions into Naga areas to weed out armed groups. The Naga underground groups targeted those they suspected were collaborating with the Indian and Burmese armed forces.

The way to Tuensang was paved with bad roads, and interrupted by blockades and stray dogs. The young man who drove me here the second time said that, when he was young, they named these dogs after the Indian Army soldiers—Mishra, Natarajan, Singh and Mukesh—and chuckled.

I travelled through Nagaland at the height of the Bodo agitations. Members of the separatist Bodo people, who have been demanding a separate statehood in Assam for decades, were renewing the attacks on refugee Muslims that had begun the 1990s. As a result, the main roads had been blocked, and essential vegetables, fruits and pulses usually transported across state lines were in short supply. Smaller hotels and restaurants were closed. I had to buy lentils, rice and spices, and carry them with me on the road—often offering rice and lentils to a family in return for use of their kitchen. A three-day shutdown and roadblock had completely paralysed the state.

The church’s presence was ubiquitous; each small hamlet and village came with a quaint church and local school as 90 per cent of Nagaland is Christian. I spoke with a local pastor in the remote Tuensang area who wondered if India sought to keep this region as a buffer state, backward and underdeveloped: ‘Look what happened to Tibet and Afghanistan, “buffer” means we are merely pawns, we are not a working part of the country. It also means that we are dispensable. Many of our children leave for the mainland but never quite fit in. They face so much racism.’

The government abuses of the 1950s and ’60s right up to the ’90s became the many circles of the inferno. There were cases of beheading, burning people alive, torture and mutilation. Some of these tortures and killings were committed publicly in front of the whole village. Three years later, I would hear the story of a schoolteacher in Kupwara, Kashmir, in a border village. He was beaten to death in the village square in the 1980s. Public executions and extra judicial killings of civilians are a tried and tested counter-insurgency strategy of inflicting terror, and have been used across time and geography in India and elsewhere. Modern states, including the United States, Israel, France and many others, continue this practice to date.

As the resistance and rebellion spread into Naga Hills, in April 1956, the ‘responsibility of maintaining law and order’ was handed over to the Indian Army. In 1956-57, the Ministry of Defence defended the violence, stating that ‘due to hostile activity by misguided Nagas, the law and order situation deteriorated in the Tuensang area of the North Eastern Frontier Agency.’

The ‘grouping’ of villages began immediately and continued into 1957. In February that year, the whole population of Mangmetong and Longkhum were moved into an enclosed area. Families of individuals who had joined the rebellion were further segregated from the ‘general’ population. The grouping was often followed by ‘burnings’.

The soldiers would inform the village headman that his village was about to be burnt. In Mokokchung district, almost every village was burnt, several times over. Mongjen village was reportedly burnt seven times, and Mamtong nineteen times, before the villagers finally surrendered. This method was justified as being used to cut off access to food and shelter to the insurgents and those resisting the Indian state, but it resulted in mass starvation and homelessness. Multiple search operations and curfews accompanied the grouping and burning operations.

Sometimes the regrouping took place long after the village had been burnt, and the villagers spent the intervening period in the jungles or fields around their former homes. We walked to some of the remote border villages, many inaccessible and only reachable by a long trek. Many of the women we met refused to speak, and many had never encountered an outsider, except the Indian soldiers.

Ya was close to eighty when I met her in a remote border village in Tuensang district. Almost sixty years ago, as she was on the way to her fields, an Indian Army patrol convoy raped her. She doesn’t remember how many men there were, or their faces. They all became one violent, faceless nightmare. When she recovered consciousness, she discovered many ‘marks’ on her body, and she was bleeding profusely.

‘They had left me to die alone.’

The story of her rape soon spread. It was one of the first known instances of rape by Indian soldiers, and she was left to die on the street by the soldiers to send a message. She remained alone her whole life: ‘No one was willing to marry me, I got no help.’

‘I am not the only one,’ she told me, her face still stoic.

Every family had these gruesome stories. And many of the women lived in shame and pain because of what was done to them.

It was late afternoon when I left Ya’s house, and my translator friends walked ahead. I walked towards a border pillar across the old helipad built by the Japanese during the Second World War. Without realising, I found myself on the Burmese side of the border.

I knew I was in Myanmar because the Burmese border security guards I ran into informed me that I had crossed the border, and I was quickly taken into their custody. The men spoke in a mishmash of English and a language I didn’t understand. They explained that they had to inform their Indian counterparts on the other side of the border, the Assam Rifles, who would come and pick me up. I was not allowed to walk back unaccompanied, even though I was just ten yards away from ‘India’. When I protested, I was told that the penalty for border crossing was three year in Burma. I had to choose—they could take me to the nearest police station inside Burma, a day’s drive away, where I would face charges. Or I could wait for the Indian soldiers.

Mere hours before, I had heard Ya tell me about her ordeal, and the women who sat next to her had listed their own dark encounters with the Indian military. A few weeks earlier, Toyoba, a Rohingya refugee I met in Calcutta, had told me about the brutality that the Burmese border security force, the Nasaka, had inflicted on his family. He had told me stories of raped women, dismembered bodies and burnt-down mosques.

I felt an unexplainable emotion—sickness in my gut, a mix of disbelief and disgust. I had never felt this specific fear before. When I felt a hand on my backpack, I froze. Were they about to grab me, like they had grabbed Ya? I shuddered.

The fear made me heavy, and I found it difficult to move.

The men spoke politely, offered me pork stewed in pickled bamboo shoot. I waited patiently for the soldiers from India to arrive and take me back. Two hours later, five soldiers arrived, looking excited. I was told this was the most exciting thing that had happened here in a long time.

The soldiers from opposite sides of the border greeted each other like old friends. The Indians offered to make tea with the firewood, and the Burmese set their radio to the AIR station. In this part of the world, the radio frequencies and cell phone towers could pick up signals from both sides. The soldiers complained about their commanding officers and drank their tea.

There was no official handing-over ceremony: once the tea was finished, everyone got up to leave. Before we went, the Burmese soldiers alerted the Indian soldiers to a body they had spotted recently while scouting the no man’s land between the two countries. ‘Not ours’, the Indians responded. ‘Must be the locals settling scores.’ With quick banter, the matter of the unidentified dead body was settled, and I was escorted back across the border. The soldiers dropped me off at the guesthouse and told me to stay out of trouble.

I went inside and locked myself in. When I reached for my notebook, it was gone; I had left it across the border in Myanmar. I flung my phone across the room in rage and broke into tears. I did not know why I was crying.

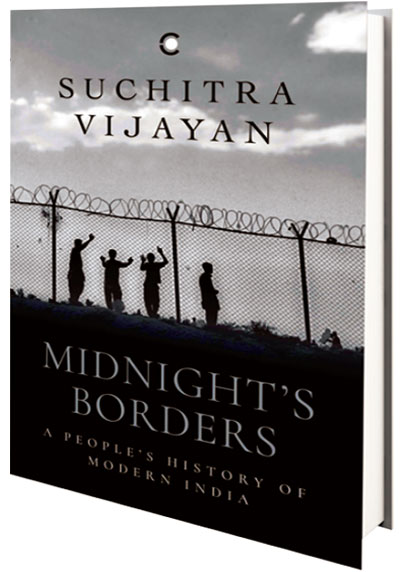

MIDNIGHT’S BORDERS: A PEOPLE’S HISTORY OF MODERN INDIA

Suchitra Vijayan

Context (Westland Publications), Pg 249, Rs 699