Blow Hot Blow Cold

Sikkim resists the chilly winds blowing from China

Pravin Sawhney and Ghazala Wahab

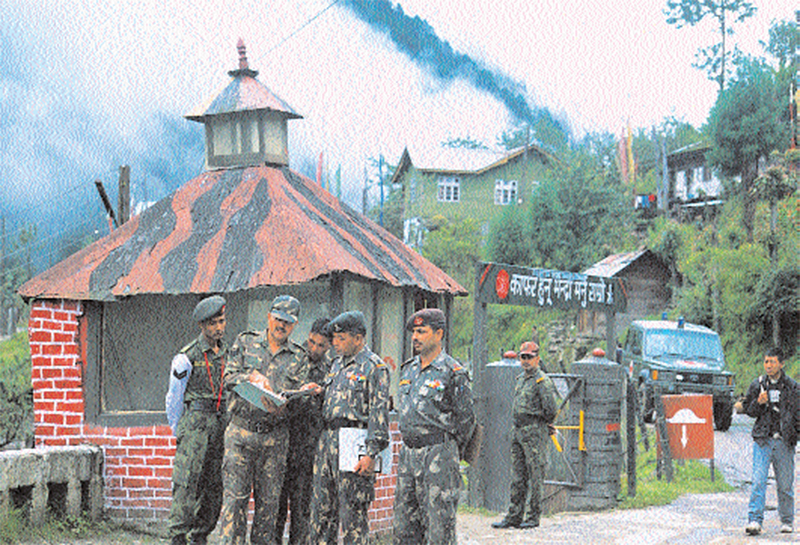

The dynamics of India-China politico military relations are best evident in the state of Sikkim: here India has the highest concentration of troops anywhere in the world against a virtually non-existent adversary. India’s entire 33 corps and elements of Assam Rifles are pitted against China’s meagre Border Defence Regiments (BDR), which are an equivalent of India’s paramilitary forces. In terms of numbers, India has allocated nearly 40,000 regular troops for Sikkim, of which, at present, 8,000 are physically holding forward positions against about 400 Chinese paramilitary forces located 18 to 20kms away from the border. According to Maj. Gen. Avadhesh Prakash, General Officer Commanding, 17 Mountain Division based in Gangtok, the capital of Sikkim, “We are well prepared in defence posture and defence preparedness as compared to Chinese forces.” What he implies is that, unlike China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the Indian Army has adopted a defensive posture, with the unsaid political directive that every inch of Indian territory must be guarded. The Indian military posture against China is to maintain full strategic defence with minor tactical offensive capabilities. Given the politico-operational compulsions, difficult terrain, and PLA’s track record, it is clear that the army is doing an onerous task.

Even as China has finally shown Sikkim as a part of India in its World Affairs Yearbook 2003-2004, published in May 2004, politically, the matter is far from settled. This is evident from the fact that following the Yearbook and the mention in its official Website, the official Chinese maps are understood to still showing Sikkim as an independent country as late as March 2004. China had all along kept the Sikkim question outside the Sino-India border dispute saying that the Tibet-Sikkim border issue falls outside the purview of the disputed India-China border. Beijing had maintained that Sikkim is an independent country whose borders with Tibet were sought to be delineated by the British government in India by the 17 March 1890 convention. Considering that China has now amended its World Affairs Yearbook, two questions remain: No Chinese leader has publicly said that they accept Sikkim as a part of India. In fact, the Chinese foreign ministry spokesman, Kong Quan emphasized after the publication of the World Affairs Yearbook that, “Sikkim, an enduring question left over from history, cannot be solved overnight. It will be required to be solved in a gradual manner.” And importantly, Beijing has not said that it accepts Sikkim’s well-defined border with Tibet. Based on the authority of the 1890 convention, when Tibet was a strong nation and China was contend accepting the powerful British Indian government’s protectorate over Sikkim, India believes that the border between Sikkim and Tibet is well-delineated and demarcated. The moot thing is that communist China has never said so. Hence, unless the Chinese leadership says so, dispelling all doubts on this count, India will require resolving the Sikkim-Tibet border independent of the border dispute with China. “Until then, it will be unrealistic to expect the army to further thin down its presence in Sikkim,” says a senior officer at 33 corps headquarters.

Also Read:

Dragonfire

To mark the first anniversary of FORCE in August 2004, we decided to turn east. FORCE visited Sikkim in July 2004, an area with the highest concentration of troops in the world. In the week that we spent there, FORCE travelled to both Nathu la and North Sikkim. The result was this comprehensive cover story, spanning past, present and the future. Read on

Sikkim has an area of approximately 8,000sqkm, measuring 113km north to south, and 64km from east to west with heights rising up to 28,000ft. Militarily, the state is divided into north and east Sikkim. Due to a central massif, north Sikkim is further divided into Muguthang Valley in the west and Kerang plateau in the east, and north-east Sikkim. The Lachung, Lachen and Muguthang Valleys in north Sikkim prevent any lateral movement. Of the 14 passes along the 206km long Sikkim-Tibet border, six are all-weather, implying that these are open throughout the year. Three each in north and east Sikkim, the passes are Kongra La, Bomcho La, Sese La, Nathu La, Batang La and Doka La. Unlike the passes in north east and east Sikkim, the passes on the watershed border in north Sikkim are fairly wide and motorable. Being windswept, they remain relatively free from snow and are open throughout the year. The watershed and the adjoining Tibetan Plateau are devoid of any cover. The terrain in north and north east Sikkim is more difficult, rugged and formidable with the altitude rising suddenly and steeply (one can travel from 5,000ft to 14,000 in just about 60km) than east Sikkim where surface communications are better developed due to its proximity to the north Bengal plains. India’s 435km-long border with Nepal includes a 125km border between Nepal and Sikkim of which about 50km is most inhospitable.

Division, ‘We are well prepared in defence posture and

defence preparedness as compared to Chinese forces’

Sikkim’s strategic importance is underlined by the following facts:

- It adjoins Tibet in the north and east, Bhutan in south east and Nepal in the west.

- It provides depth to the Siliguri corridor, which is 180km by 75km, with the neck of the corridor being 20km. The corridor comprises four districts in West Bengal, Dinajpur, Cooch Behar, Jalpaiguri and Darjeeling. If China were to sever this corridor, probably with support from Bangladesh, India would loose contact with Assam and other North-Eastern states. This is precisely what Pakistan’s foreign minister, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto had suggested to his Chinese counterpart during the 1965 India-Pakistan war.

- It outflanks the Chumbi Valley of Tibet in the east. The width of the Valley in the north is 25km and tapers down to three to four km in the south. The Chumbi Valley has well-defined roads and tracks which terminate in passes. As the Valley has a restricted deployment area, it favours offensive operations. Towards the southern tip of the Valley, China has its claim area of Doklam plateau in West Bhutan made as recently as 1993.

It projects into the Tibetan plateau.

Given the strategic importance of Sikkim, the army has identified three levels of threats from the PLA. The first is PLA’s Border Management Posture which is wholeheartedly offensive in nature. With little territorial claims and designs in the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR), the Indian Army has adopted a defensive Border Management Posture, which has two elements: to hold the passes which are likely ingress routes round the year, and to undertake regular internal patrolling to ensure that there are no intrusions made by the adversary. For example, with Singalia mountain range and huge massifs in west Sikkim, PLA intrusions in the adjoining Muguthang Valley of north Sikkim will be resource and logistics intensive and, therefore are unlikely. However, in the Kerang Plateau, Giaogang and Dongkya La provide the key to the Lachen and Lachung Valleys. Therefore, the army has ensured by its presence that these launch pads are denied to the adversary. Similarly, the threat in north east Sikkim comes from Tangkya La, Phimkaru La and Gora La in the same order, as these provide shortest routes to Chungthang, a prominent town on the North Sikkim Highway (NSH), which links up with Gangtok in the south. In the mountains, the likely ingress routes are along the rivers, which are the Teesta, running from north to south, and the Dongkya La Chu in north-east Sikkim. In east Sikkim, the Indian Army holds all passes except Jelap La which is held by the BDR troops. However, the dominating shoulders of this pass are with the Indian Army.

The Nathu La pass at 14,438ft in east Sikkim is peculiar as both sides maintain defences within 20m of each other. Unlike all other passes, here the BDR soldiers maintain a physical presence for three reasons: One, twice a week, Sunday on Indian and Thursday on the Chinese side, both exchange mail bags at this place. A concrete building marked ‘International Post Office’ on the Chinese side is 10m from the fencing which separates the two countries. According to army officials, there are adequate letters between the people divided by the border to be exchanged every week. As a rough guide, human settlements in north and north east Sikkim are about 50 to 100km from the border, and in east Sikkim, 30 to 40km from the border. Two, since November 1999, the two sector commanders (brigade commanders) are connected with a hot line which is used frequently for reasons ranging from informing one another of important visitors coming to Nathu La, to impending blasting being done by either side to improve defence works, or simply to exchange greetings. Moreover, with Indian tourists permitted up to Nathu La four days a week, both sides understand the importance of displaying good-will. And three, sector commanders hold bi-annual meetings at Nathu La; the Indian side host the Chinese delegation on 15 September, and the Chinese do so on 15 May each year. Started in September 1995, a total of 18 meeting have been held so far.

Small and big level threats are the other challenges faced by the army. According to senior commanders, in the small level threat, the PLA could launch a limited offensive to ensure the security of Chumbi Valley, or capture areas in north and north east Sikkim to deny launch-pads to the Indian Army. This would require the PLA to muster two divisions worth of strength, which it could do with little effort. On the other hand, the big level threat would require PLA strength of 18 to 20 divisions. This would imply a threat to or an attempt to sever the Siliguri corridor, and to capture the important towns of Gangtok, Rhenok, Rangpo or Siliguri. Moreover, the PLA could capture areas in west Bhutan which it has claimed since 1989. Even as the big level threat looks improbable in the foreseeable future, and it is assessed that adequate warning would be available before it materialises, there is unease over PLA’s Border Management Posture which could snowball into the small level threat. The Indian Army deployments in Sikkim are primarily meant to thwart these low level designs. Considering that the Indian government would be extremely reluctant to open a military front against China, PLA’s shenanigans in Sikkim, if not checked in time, could become a political and diplomatic embarrassment. Moreover, as the PLA is known to have transgressed the Line of Actual Control (the disputed border) in nearby Arunachal Pradesh on many occasions, a determined action by the Indian Army there could encourage the PLA to open a second military front in Sikkim to release pressure. The 33 corps headquarters, therefore, has an added responsibility to monitor the development in the more active 4 corps headquarters in Tezpur meant for Arunachal Pradesh. The defensive operational tasking of 33 and 4 corps are intertwined. For this reason alone, suggestions that with limited military activity in Sikkim, the army could dispense with 33 corps headquarters make little military sense.

According to officers, troops permanently occupying positions in higher altitudes require three levels of acclimatisation; the first level is at 10,000 feet, the second at 15,000 feet and the third is at 17,000 feet and more. “In addition to the super altitudes, the Kerang Plateau has an extreme wind chill factor which is unknown on the Siachen glacier,” says the Brigadier General Staff, 33 corps headquarters, Brig. S.S. Kumar. Notwithstanding such adverse climatic conditions, “Troops on altitudes of nearly 18,200ft are not authorised any special food or allowances like the Siachen allowance,” says Brig. Clement Samuel, the new commander of the north Sikkim brigade. It is well known that even at the Siachen glacier, the casualties are more because of the inclement weather rather than the enemy firing. “Evacuation of casualties is done by the helicopters of the aviation corps, but beating the weather for the purpose is a big challenge,” says a senior officer.

The problems gets aggravated as, unlike the troops in the west facing Pakistan, Sikkim is on a low priority for almost everything ranging from special clothing, to providing entertainment to troops cut-off for months on forward posts, modern equipment like Hand-Held Thermal Imagers and night vision devices for patrolling purposes, Advance Winter Stocking (AWS) and Advance Monsoon Stocking (AMS) by animal transport, modern rifles and land based firepower. “The AWS and AMS is for periods of 90 days and 45 to 50 days respectively with maximum help from porters and own troops,” says an officer. Moreover, a majority of Assam Rifles’ troops have the old 7.62mm rifles, which is explained by the fact that they are under the Ministry of Home Affairs. It is another matter that being under the command of the army, the Assam Rifles troops will need to function as regular troops.

It is axiomatic that limited funds would affect the defences as well. A rough comparison can be made from the fact that 33 corps gets a total of up to seven crores annually for defence works, while the newly-raised 14 corps in Ladakh gets over 100 crores every year. Even as AN-32 aircraft are available for air maintenance and casualty evacuation, there are limited Dropping Zones in north Sikkim. Let alone the frugal funds, maintaining defences meant for over a division by a strength of under two brigades is a difficult task. “During the annual operational alert which lasts from 15 September to 15 November, troops find it arduous to maintain extensive defences,” says a colonel. Although a few Steel Permanent Defences, which can take a direct hit of a 105mm calibre shells have come up, most living and operational bunkers leak and need regular maintenance, says a major.

That apart, roads remain an endemic problem in Sikkim, which is compounded by the twin assault of weather and terrain. There is only one main artery, the National Highway 31A that links Gangtok with Siliguri in north Bengal. Jawaharlal Nehru Marg (JNM), named after the first prime minister, who converted the dirt track into a black-topped road in 1958, connects Gangtok with Nathu La. Though singlelane roads, these two are the only ones which seem to resist the vagaries of weather. But movement on the JNM is impeded by heavy fog and low-hanging clouds which in monsoons reduce visibility to less than 10m. The other crucial passes in the east are connected only through unmetalled roads. The sparsely-populated and vulnerable north Sikkim is connected through a North Sikkim Highway (NSH) from Gangtok to Giaogang via Chungthang which is also the confluence of River Teesta and Lachung. From Chungthang another road goes east via the Lachung Valley towards Zadong in the Kerang plateau.

Currently, the NSH is the only lifeline that connects Gangtok with north Sikkim and consequently the plateau region. Essentially a Class 30 road, militarily the weakest link on this is a Class 12 bridge. However, the weakest link on this road is impact of weather, which renders the road non-existent in parts. Innumerable waterfalls and springs run across the road, which in monsoons make driving dangerous. Steep ascends and descends through sinking soil, shooting rocks and landslide prone slopes and gushing streams make this road a nightmare even on a good day. To cheer the frazzled driver, the BRO and the state government has placed thoughtful messages all along the road: ‘You have seen the Niagara Falls, now drive through Myanchhu Falls’, ‘Tasted Coca Cola? Now see Lantha Khola,’ and so on. Lantha Khola, incidentally, is not a Sikkimese soft drink. It is a highly precarious stretch which was closed for traffic for 63 days last year following severe slides.

The problems are compounded by the fact that this is also a single lane road, which implies that every time you see an oncoming vehicle, you have to either veer very close to the mountainside or balance precariously on the ridge side, hoping that the road does not sink below your tyres, to let the other vehicle go by. The responsibility of maintaining this road rests with the army which is reluctant to invest too much money in it. It reasons that the lifespan of the road is over. Either it needs to be abandoned completely or major reinforcements are required to make it motorable. To tide over the monsoon mania, the army has posted monsoon detachments all along the road, which carry out temporary clearing and repair work in case of a landslide or retrieve vehicles that slip down the edge. “But these are temporary means,” points out Brig. Samuel. “What we need are solutions.”

Hence the army has proposed to build an Alternative NSH, taking over the existing track from Singtam in south Sikkim to Dikshu and then to Sanglang. From Sanglang, the road goes towards Toong covering a distance of 42km, of which 30km is completed and after that it will culminate in Chhaten, about 70km short of the plateau, where the existing NSH finishes. The ambitious road, however, is stuck at two places at the moment. The state government is reluctant to give up its stretch of Singtam and Dikshu to the army as it plans to develop it on its own. Besides, beyond Toong, the road will have to traverse a few portions inside the Kanchenjunga Reserve Forest. Once the state government objected, the army appealed in the Supreme Court which directed the disputing parties to sort out the issue by carrying out joint surveys.

Gen. Prakash says, “We have made our presentation to the state government. The report is now with the ministry of environment. We have assured the state government that we will be using the road sparingly. We are hopeful that the issue will be resolved soon.” However, this optimism is not shared by the chief secretary of the state, S.W. Tenzing who categorically says, “I am against the Alt NSH. I don’t see any reason for that. A road has to be economically viable. Even today, there is hardly any traffic on the existing highway. The army can easily repair that road.” What neither says is that the alternative highway will probably not be open to civilian population, which is why it does not suit the state government. But if the army were to repair and relay the existing road then it will also help tourism in north Sikkim. And therein hangs the road.

Also Read:

Baggage of History

Through the centuries, Sikkim has attracted nibblers

Seal of Trouble

The 1993 agreement adds to woes of the Indian Army

Breathing Fire

China has always kept India on tenterhooks

The Red March

While PLA builds capabilities in Tibet, India watches on the sidelines

Matching Steps with PLA

India should focus on improving its border management against Tibet

I Want Sikkim to Remain an Oasis of Peace

Chief minister Pawan Kumar Chamling is an icon in Sikkim. He peers down from street hoardings, his face smiles from the front pages of the local newspapers and his name is reverentially invoked in conversation by the local population. Given that he is currently running his third term in a row since his Sikkim Democratic Front (SDF) came to power in 1994, his popularity is on an all-time high. As usually happens with icons, innumerable stories about him float around in the mint fresh air of Sikkim. A famous one goes that when he was a member of the legislative assembly in 1993 he raised his hand in the house to make a point. However, the Speaker, under the influence of the then chief minister, Nar Bahadur Bhandari, disallowed him from speaking. Chamling took out a candle from his pocket and went around the house as if searching for something in candlelight. He ended his search by coming to the well of the House and saying in a clear voice, “I am looking for democracy in this House. Since it is not here, perhaps it is in the pockets of the chief minister.” A direct consequence of this cry for democracy was that his one-year-old party, SDF, swept the polls in 1994 and has been in power since. Born in 1950, to Nepalese-speaking parents, Chamling has authored a number of books, both in verse and prose. Apart from that, a few volumes of his collected speeches are also available. A recipient of a number of awards, including Chintan Puraskaar in 1987 for poetry, Bharat Shiromani in 1996 for national integration, public welfare and strengthening democracy and the Greenest Chief Minister of India in 1998, Chamling has successfully created an image of a visionary that elevates him from the status of a mere politician. He spoke to FORCE about the opening of the trade route and other issues related to the development of this border state.