Baggage of History

Through the centuries, Sikkim has attracted nibblers

Pravin Sawhney and Ghazala Wahab

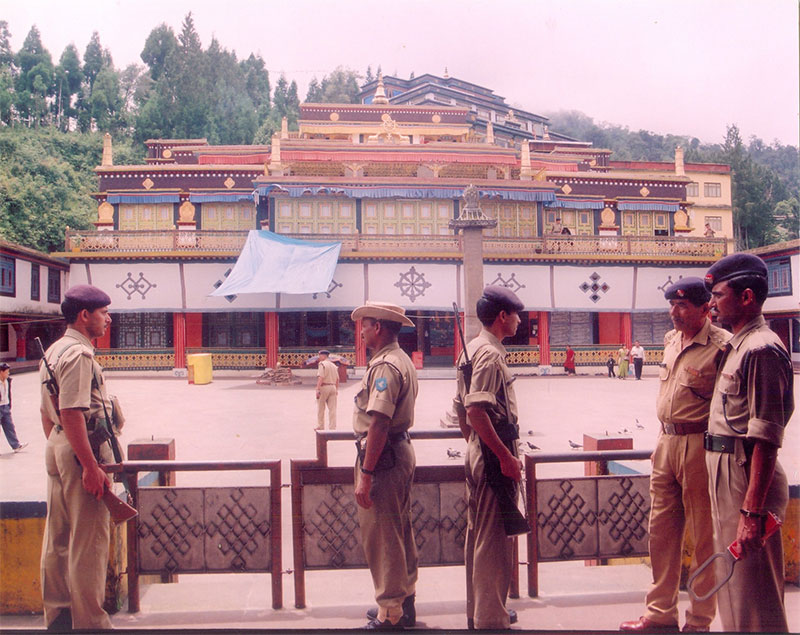

Nestling calmly in the eastern Himalayas, Sikkim is a quaint place. The state capital Gangtok is quietly cosmopolitan in its own way, with discotheques and coffee shops, yet it continues to hugs its traditions quite fiercely lending the place a romantic touch. The lush greenery, interspersed by waterfalls even in the city ensures that the increasing vehicular pollution does not reach unmanageable limit. Given the dearth of space, people have built tiny balcony and terrace gardens which are in bloom in the monsoons sprouting an array of colourful flowers including gladiolas. So you smile when chief minister Pawan Chamling says that he wants Sikkim to turn into a kingdom of flowers. But when he says wistfully that he wishes Sikkim to remain an oasis of peace, you can only nod ponderously. He, of all people, understands how difficult a task that is given that geography and history has always played cruel games with this tiny Himalayan state. Its location, Nepal in the west, Tibet in the north, Bhutan in the east and British India in the south ensured that the neighbouring states covet this lush and well-endowed kingdom and constantly nibble at its territory.

Though Sikkim’s borders with its neighbours are not disputed, its boundaries with Tibet are not explicitly demarcated on ground; a fact, leftover by history and ignored by the present in the hope that it would not rear its ugly head in the future. Perhaps, the then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru was seeking this assurance from the Chinese when he wrote in 1959 to Chou Enlai, “The boundary of Sikkim, a protectorate of India, with the Tibet region of China was defined in the Anglo-Chinese Convention of 1890 and jointly demarcated on the ground in 1895, hence it is not disputed.” However, Chou En-Lai was in no mood for assurances. He skirted the subject by writing back, “Like the boundary between China and Bhutan, the question does not fall within the scope of our present discussion… China is willing to live together in friendship with Sikkim and Bhutan without committing aggression against each other and has always responded to the proper relations between them and India.” He did not specify for how long China was willing to live peacefully with India. As history shows, it wasn’t very long before they committed aggression in 1962.

Also Read:

Dragonfire

To mark the first anniversary of FORCE in August 2004, we decided to turn east. FORCE visited Sikkim in July 2004, an area with the highest concentration of troops in the world. In the week that we spent there, FORCE travelled to both Nathu la and North Sikkim. The result was this comprehensive cover story, spanning past, present and the future. Read on

The Sikkim issue has been even more delicate because China showed some semblance of recognising it as part of India only in 2003, and that too by simply removing Sikkim as an independent country from their Website and mentioning it in their Annual World Affairs Yearbook 2003-2004. No Chinese official either said this verbally or gave it in writing; moreover, the official Chinese maps continue to show Sikkim as an independent country. The trouble with China’s relations with Sikkim dates back to the very inception of state, when it was considered a protectorate of Tibet. And as far as the demarcation of the border was concerned, though signatory to the 1890 Anglo-China Agreement, the Chinese ensured, sometimes using Tibet as an excuse, that the borders were never formally demarcated on the ground despite repeated attempts by the British.

The earliest recorded history of Sikkim dates back to 1642, when three Buddhist monks from Tibet came to western Sikkim and consecrated a boy, Phuntsog Namgyal as the first Chogyal of Sikkim. A Chogyal was meant to be a holy king, entrusted by the gods to take care of this small piece of land. Though an independent kingdom, Sikkim shared a special relationship with Tibet and by that extension with China. The ancient Sikkimese, the Lepchas, believed that they were created when the almighty created the great rivers Teesta and Rangeet along with their patron deity Mountain Kanchenjunga (pronounced as Khangchendzonga in Sikkimese). However, over the centuries, Tibetans, essentially the Bhutias, continued to pour down in Sikkim and were accepted by the Lepchas as the more enlightened partner. With Bhutias came Buddhism and the subsequent monarchy. However, the relationship with Tibet continued to be strengthened and neither Sikkimese nor Tibetans followed any borders. For the inhabitants of the barren, cold and dry Tibetan plateau, Sikkim was the grassland. Similarly, Sikkimese moved freely across the natural watershed for trade and commerce. And both Tibetans and Sikkimese looked up to the Chinese authorities. This was made clear by the Sikkimese Maharaja in 1886, to the British who were asking him to come to Calcutta to discuss the Sikkim-Tibet issue when he told the British officials, “For generations past and up to the present time, it has been the custom for the raja of Sikkim to attend to the orders received from the great officers of China and Tibet and it is not a new custom that I am introducing.”

Given that China-Tibet relationship was slightly mercurial, depending upon who was powerful at what stage, the Chinese never openly asserted themselves, preferring to maintain a status quo. It was generally understood that the Dalai Lama was the spiritual head and the Manchu king was the temporal one. Though Chinese had posted two representatives at Lhasa, called Ambans, their influence in Tibetan politics depended upon how powerful Tibetans were at that point. On their part, Tibetans and Sikkimese were both fearful and wary of China. Besides, for simple- minded Tibetans, who were deeply concerned about preserving their culture, religion and the way of life, China was a convenient go-between to deal with the outsiders. However, this convenient state of affairs changed as the British realised the economic potential of the region sometimes in the middle of the 18th century. Fables and accounts by travellers coupled with the growing competition that the British faced in India from Dutch and Portuguese merchants compelled them to look towards the north east. Tibet was still more of mystery then with stories of untold wealth, including gold.

The political situation in Tibet, Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan in 1760s gave both the British and the Chinese an opportunity to make their moves in Tibet. They cashed on Bhutan’s aggression in Cooch Behar in the present day north Bengal. Since, the Bhutanese king knew the Panchen Lama, headquartered in Tashi Lhinpo in Shigatse, which is north of Chumbi Valley, the British intervened in the conflict, settling matters in favour of Bhutan so that they get an introduction letter to the Panchen Lama. After much dithering, the Panchen Lama entertained the British mission in Tashi Lhinpo in 1774. The British envoy, George Bogle managed to win over the Panchen Lama, who confessed to him that Tibetans were wary of foreigners, especially, Europeans whom they believed to be expansionists and hegemonic. Bogle used his growing rapport with the Panchen Lama to study the trade potential in Tibet and came back convinced that it was a great market waiting to be flooded by the British goods. The English believed that Tibet would be the first step towards reaching the markets in China.

The early hopes ended equally early with the deaths of the Panchen Lama followed by Bogle. While the British dwelled on their next move, the Gurkhas of Nepal attacked Tibet, who failing to get any assistance from the British signed a peace treaty with Gurkhas promising to pay them yearly tributes. However, the Tibetans reneged on the agreement on the plea that it was not ratified by the Dalai Lama. The Nepalese attacked again in 1792 and this time the Chinese came to their rescue. They not only drove the aggressors out but also annexed the Chumbi Valley which was technically a part of Sikkim but was generally shared by them and the Tibetans. The Chinese also took the opportunity to quickly survey and mark the southern border of Tibet with Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan. With this, Tibet was once again out of bounds for the British; hence they switched attention to Sikkim which was found to be a more pliable state. A treaty agreement, called the Treaty of Titalia, was signed between British India and the Maharaja in 1817, by which Sikkim became almost a British protectorate. In the history of Sikkim, the Treaty of Titalia was the first defining moment which would determine its subsequent future. By this treaty the Chogyal agreed to submit all his territorial disputes to the British for mediation, not to levy duties on British merchandise, to allow Europeans and Americans to stay in Sikkim only after seeking permission from British and to extend protection to the merchants from Company’s provinces.

Hence, despite being banished from Tibet, by this treaty the British could do trading right up till the Tibetan border without paying any dues. A few decades later in 1830, the British opened negotiations with the Chogyal once again for the transfer of Darjeeling. Even as the negotiations for transfer continued between the two parties, the British twisted the language in one of the corresponding letters, implying that Sikkim had agreed to transfer Darjeeling without any conditions. The hill station was then taken over by them. Though subsequently, the British agreed to pay an annual compensation for Darjeeling, the relations between the two had soured to such an extent that the British even waged an unsuccessful war against the Himalayan kingdom. Meanwhile, relations between Sikkim and Tibet remained warm even as British resumed efforts to make a breakthrough in Tibet. This was evident by the fact that even as Tibetans were giving a hard time to the British, the Sikkimese king was holidaying in his palace in Chumbi valley, which was now part of Tibet-China.

By this time, the British realised that Chinese wielded a lot of influence with Tibetans, hence it was much better to approach the issue through them. As British kow-towed to Chinese, they played a double game. On the one hand, they impressed upon the British that Tibetans were obtuse people, wary of foreigners so should be left alone and on the other hand, they prevailed upon the lamas in Tibet that British had hegemonic designs. Even the Sikkimese king didn’t help as he told the British to wait. It was around this time that the British asked the Sikkimese king to come to Calcutta to discuss the Tibetan issue, and he refused to come pointing out that he must take the Chinese wishes into account. The Chinese, in any case, maintained that Sikkim was a dependency of Tibet, which by extension implied Chinese dependency.

The second landmark in the history of Sikkim was in 1889, when the British established its residency in Gangtok with J.C. White as its first political officer. The following year, they signed the 1890 agreement with the Chinese without taking either Sikkim or Tibet in consultation whereby China recognised Sikkim as a British protectorate and accepted that the British government was to have, ‘direct and exclusive control over the internal administration and foreign relations of that state. Except through and with the permission of the British government, neither the ruler of the state nor any of its officers were to have official relations of any kind, formal or informal, with any other country.’ Thus the king was effectively reduced to a mere titular head. The agreement also defined the boundaries between Sikkim and Tibet and soon after the signing of the agreement the British asked the Chinese to demarcate the border between the two countries. China tried to involve Tibetans in the process but they remained obstinately aloof. Even as the British were trying to involve the Chinese in drawing the borderlines, Tibetans occupied the Giaogong area in north Sikkim. When Chinese expressed the desire to put-off the process of border demarcation, the British unilaterally went ahead and put border pillars in Jelep la, Donchuk la and Doka la in east Sikkim which the Tibetans promptly removed as they refused to recognise the border defined by the 1890 convention. Moreover, the Tibetans refused to accept the watershed in the north as a natural boundary which the British were at pains to explain to them. The border issue continued to fester with Chinese expressing their helplessness over Tibet’s obstinacy. Finally, Tibetans came to the negotiating table in Yatung in the Chumbi Valley in 1898 with their version of the boundary, which put all the areas north of Donkya la, Giaogang and Lhonak Valley as part of Tibet. The discussions reached a deadend. When the 13th Dalai Lama came of age, he repudiated the 1890 agreement on the grounds that Tibetans were not a part of that. Following its defeat in the Sino- Japanese war of 1894-95, China’s influence in Tibet had waned considerably.

As far as the demarcation of the border was concerned, though signatory to the 1890 Anglo-China Agreement, the Chinese ensured, sometimes using Tibet as an excuse, that the borders were never formally demarcated on the ground despite repeated attempts by the British

Finally, the British had to give up enforcing the 1890 Agreement and it tried to talk directly with Tibetans. Even this did not meet with much success as the Dalai Lama used the old plea saying that he is not authorised by the Chinese to speak directly with foreigners. Clearly, both Tibetans and Chinese used one another when it suited them. Meanwhile, reports started appearing that Russia was making successful inroads into Tibet. This created panic among the British and they finally decided to take on Tibet militarily. Francis Younghusband led a mission via Jelep la to Lhasa which left a number of lamas dead on its way. The Dalai Lama escaped to Outer Mongolia after appointing a regent, who signed the convention with the British in 1904, by which he accepted the 1890 Agreement and the Tibet- Sikkim boundary defined by it. But Tibetans once again wriggled out of the actual demarcation of the border. To ensure that there remains a buffer between British India and Russia, the English signed a convention with the Chinese accepting its suzerainty over Tibet in 1906, thereby removing any buffer between India and China. Yet the boundary issue was not resolved and over years the British didn’t feel the need to put any boundary pillars. That the Tibetans were still not convinced about the border as envisaged by the British became clear in 1934 when some Tibetan official came to Sikkim to survey the southern Tibetan border. He marked the southern Tibetan border as running through Giaogong and Donkya la.

Having failed to demarcate the boundaries officially, British started changing the demography of the state by encouraging massive influx from Nepal. The Gazetteer of Sikkim 1894, justifying the influx of Nepalese recorded, ‘…those hereditary enemies of Tibet was the surest guarantee against the revival of Tibetan influence. Hinduism will assuredly cast out Buddhism and the prayer wheel of the Lama will give place to sacrificial implements of the Brahmin… Thus race and religion, the prime movers of the Asiatic world will settle the Sikkim difficulty in their own way.’

By the time India inherited Sikkim after Independence, the demography had changed completely. According to the latest census, 77 per cent of Sikkimese are of Nepalese origin, 13 per cent Bhutias, seven per cent Lepchas and three per cent others. The ruling community remained Bhutias till 1975, when the movement for democracy and merger with India, spearheaded by Nepalese succeeded and Sikkim became the 22nd state of India. Nepalese wanted democracy and merger with India as they feared expulsion or a wretched existence under the Chogyals. Moreover, they felt that in a democracy they would come to power by sheer numbers. The sentiments were not unfounded. Today, Nepalese is the state language and the state sends a Nepalese origin person to the Lok Sabha while a Bhutia-Lepcha is sent to the Rajya Sabha. The Bhutia-Lepchas along with other notified scheduled tribes have 12 per cent reservation in the state assembly. The tribal status also implies that whenever the income tax laws of the Indian union are extended to the state (Sikkimese don’t pay income tax), the majority Nepalese community would have to pay the tax. According to the chief minister, this has been a sore point among the Nepalese, which is why they are also demanding reservation in the assembly despite being the majority community, as well as the tribal status for the whole state. Interestingly, only 30-31 per cent population of the state is tribal. “But that is the price for peace one has to pay,” reasons the chief minister.

Also Read:

Blow Hot Blow Cold

Sikkim resists the chilly winds blowing from China

Seal of Trouble

The 1993 agreement adds to woes of the Indian Army

Breathing Fire

China has always kept India on tenterhooks

The Red March

While PLA builds capabilities in Tibet, India watches on the sidelines

Matching Steps with PLA

India should focus on improving its border management against Tibet

I Want Sikkim to Remain an Oasis of Peace

Chief minister Pawan Kumar Chamling is an icon in Sikkim. He peers down from street hoardings, his face smiles from the front pages of the local newspapers and his name is reverentially invoked in conversation by the local population. Given that he is currently running his third term in a row since his Sikkim Democratic Front (SDF) came to power in 1994, his popularity is on an all-time high. As usually happens with icons, innumerable stories about him float around in the mint fresh air of Sikkim. A famous one goes that when he was a member of the legislative assembly in 1993 he raised his hand in the house to make a point. However, the Speaker, under the influence of the then chief minister, Nar Bahadur Bhandari, disallowed him from speaking. Chamling took out a candle from his pocket and went around the house as if searching for something in candlelight. He ended his search by coming to the well of the House and saying in a clear voice, “I am looking for democracy in this House. Since it is not here, perhaps it is in the pockets of the chief minister.” A direct consequence of this cry for democracy was that his one-year-old party, SDF, swept the polls in 1994 and has been in power since. Born in 1950, to Nepalese-speaking parents, Chamling has authored a number of books, both in verse and prose. Apart from that, a few volumes of his collected speeches are also available. A recipient of a number of awards, including Chintan Puraskaar in 1987 for poetry, Bharat Shiromani in 1996 for national integration, public welfare and strengthening democracy and the Greenest Chief Minister of India in 1998, Chamling has successfully created an image of a visionary that elevates him from the status of a mere politician. He spoke to FORCE about the opening of the trade route and other issues related to the development of this border state.