The Maroon Beret

Keeping up with posting one archival article a week, here is a nugget from January 2004, when FORCE visited Indian Army’s training school for Special Forces in Nahan. The first-ever comprehensive feature that covered the training as well as the transition of the Para battalions into Special Forces. 15 years later, the issues that FORCE raised then remain. Read on

With added emphasis on Special Forces, the army is set to change the face of war

Pravin Sawhney and Ghazala Wahab

When the call came in the early hours of the morning on November 30, Colonel K.K.K. Singh thought that it was one of his golfing buddies reminding him of the game. He and his family had a late night the previous day as they were scouting for a bride for their 29-year-old son at a wedding, so he was wondering if he should give the game a miss. But the caller had nothing to do with golf.

It was the call all families with sons, husbands and brothers in the armed forces dread. Col. Singh’s only son Major Udai Singh had made the supreme sacrifice for his country in the thick forests of Gamir Mugla in Rajouri sector of Jammu. Even as his family was enjoying itself at a wedding looking at the potential bride, Maj. Singh lay dead near a nullah, hit in the neck and the chest by the elusive terrorist. As his family comes to terms with the loss, one constant thought consoles them. “This is the only way he would have wanted to go,” says a close friend recounting what Major Udai once said: ‘The best end for a soldier is to die in operations.’

In his battalion, Major Udai Singh, who was recently awarded the Sena Medal for the operations he led in the Thanamandi area of Jammu, was called a lucky mascot. Whenever he would be around in an operation nobody got hurt. However, on that fateful evening of November 29, luck was apparently in short supply. He had gone out for a 48-hour operation in the forests of Gamir Mugla with his team when they came across a group of militants. Taking advantage of the thickly-forested terrain, the militants scampered for cover as did Major Singh’s team. It was around 6.30 in the evening, the sun had set and the forest was blocking out the fast fading daylight. Major Singh and another scout were leading the team. Though militants usually avoid engaging the security forces in a one to one battle, this time it was simply a question of who gets whom first. Major Udai’s team got one militant and they in turn managed to grievously injure the scout who fell in a close by nullah. In an impetuous move, which can in hindsight be termed as immature, Major Udai came out of his cover to help the injured scout who was bleeding profusely. Reckoning that if he was not given immediate help, he was likely to bleed to death, Major Udai called out to his men for help. But the cry of help sounded his death knell. It gave away his position and in one burst of fire, the terrorist hiding on the nullah got him. He died on the spot. Perhaps, in vain. Because the scout he was trying to save died too. Today, his father, though proud of his only son’s act of courage, believes that if only he was more experienced he would not have made the fatal mistake of calling out loud. Maintaining stealth and complete silence is one of the basic rules of counter-terrorism operations.

“The shortfall of officers and the ongoing proxy war, which does not seem to have an end in the near future, is taking the toll on our young, talented boys who sometimes get carried away believing that they are invincible,” says Col Singh. He has a point. Udai Singh picked up his major’s rank after only six years of service. Moreover, he was leading operations which are meant to be led by officers with greater experience.

Major Udai made up in enthusiasm what he lacked in experience. Army was the career of choice for him. Though his father was also from the services, as was his maternal grandfather, he started his career in the hospitality industry after graduating from Deshbandhu College in Delhi. He got through the management course run by the Taj Group of Hotels and started work as the front-desk trainee in Taj Mahal hotel in Delhi. However, standing behind the desk with a plastic smile was not his idea of life. For him, life had to be one big adventure. “He was a true mother nature’s child,” recalls one friend. “If one asked him to describe his life he would go in raptures about how he sleeps under a star-studded canopy with a bonfire for warmth and the cries of the bird and other nocturnal creatures for music. He would never say that he was scouring the jungle during an operation. Everything, even the most dangerous operations, was fun for him.” He quit his hotel job and joined the Indian Military Academy where he passed out in 1997 with an Artillery medal for adventure.

As a child he was hyperactive. During train journeys, because he could not keep still on his seat, his mother used to tie a long rope around his leg so that he could roam the compartment to his heart’s content without the fear of getting off the train. It was perhaps this innate urge to do more that ensured that he was not content with simply joining the army. He wanted the best, the most challenging and the most fulfilling of careers. He opted for 1 Para Special Forces. While he was on probation, his biggest concern was getting selected. He wrote to a friend, ‘If I am not able to pass the probation my life in the army shall be doomed.’ That was not to be. He passed. And passed brilliantly. He was among the few SF personnel to successfully do both, under-water diving and free fall para jumping. Moreover, he was also a green belt in karate. For him, being in the Special Forces was the ultimate high in life. To all the new incumbents he used to say, ‘Welcome to the best address in the Indian Army.’

But the best address also could not hold him for long. “Two years ago, he volunteered for the Special Group, also called Mavericks and became a part of 4 Vikas,” says his father. Though it was his adventure lust which determined his choices, there was also a desire to make a difference. And it is this desire that connects all the young enthusiasts who volunteer for Special Forces. It is not for nothing that Major Udai called I Para SF the best address in the army. Those who volunteer to join the Special Forces (1 Para is just one of the battalions), do so believing that they are joining the best force, whether it is in terms of training, tasking or prestige. Ultimately, the biggest draw is the maroon beret that these guys sport.

Major Udai’s (who had three passions in life: photography, music and travelling) just one of the poignant stories, which is made even more heart-rending by the memories his family and friends have of him. His brothers-in-arms have their own small, touching stories about life in the Special Forces. And they all have their own different reasons for the joining the force. But all of them have one thing in common: a zealousness, which can only partly be described as patriotism. One young officer, tall, good-looking with unblinking eyes, says that the sentiment of doing something for the country is always there, but ultimately it is the desire to be the very best which guides him. “I want to conquer all the limits of human endurance,” he says with a steely edge in his voice. His colleague adds, “I felt that the life in a normal infantry battalion was too dull and too mired in the mundane. Here, you feel a sense of individuality and also a sense of liberation. You are not judged in your day-to-day life but only on the results you produce.”

‘The shortfall of officers and the ongoing proxy war, which does not seem to have an end in the near future, is taking the toll on our young, talented boys who sometimes get carried away believing that they are invincible,’ says Col. K.K.K. Singh

Though nothing earth-shattering, Major Udai, his father was a maroon beret too, wanted to make a difference in whichever way possible. His family and friends recall how he always wanted to do something bigger, better and dramatic. His tenure in the Rajouri sector was his last in J&K but even before it could end he was already toying with the idea of volunteering to go to the Siachen glacier. His parents wanted him to get married, raise a family, like all 29-year-olds are expected to, but his heart was set on his work, followed by music. Though his friends used to run a mile whenever he picked up his guitar, he was undeterred. So much so, that he wouldn’t think twice before playing at a public place, unmindful of the sniggers. Queen’s ‘I want to break free was his favourite song.’ Perhaps, in his heart he simply wanted to break free.

But Major Udai’s story is a mere analogy for the young enthusiasts who join the Special Forces believing that they are a part of an elite service. As one SF officer says that even when he was at the Academy he was completely taken up by the aura of a person sporting a maroon beret. “It was clear that he was a class apart,” he recalls. Many people say that the Special Forces personnel are made special because of their training and their equipment. But as the Special Forces’ story unfolds it is clear that these young officers and other ranks are different from the rest even before they volunteer. Because it is this difference that eggs them on to begin with.

One Man Army

Cradled in the foothills of the Shivalik range, the Special Forces Training Wing in Nahan, which was raised in 1993 and got upgraded as a school in January 2003 is the dream destination for all maroon berets. It is here that the men are separated from the boys. The place itself is like a dream. Tall eucalyptus trees line the entire complex which overlooks a lovely valley. Red tiled roofs, beautiful flowers and a few simian families add to the interest of the place. With slight exaggerations, the place has all the trappings of paradise. And as in the case of paradise, you get to enter it after a lot of toil, tears and sometimes blood (spilled during training).

The commandant of the school, Col. V.B. Shinde who took over in August 2003 recounts a story with a degree of satisfaction which comes from the knowledge of having made the grade. Between 1994 and 1996, 21 para was being converted into Special Forces. Col. Shinde was part of the process. During the probation, when the men are put through a gruelling schedule to see if they are fit to be Special Forces, his colleague Lt. Col. Parmar succumbed to a fatal cardiac arrest due to over-exertion. He was required to run 30 kilometres and couldn’t cope. In that particular group of nearly 860 people, 87 went back with serious injuries, not to speak of others who didn’t get selected.

“Even today, our selection rate is only 22 per cent,” says Col. Shinde. When Major Udai wanted to pass the probation, he prepared himself by jogging the distance of nearly 30kms in the debilitating Delhi traffic everyday. Little wonder then, those who finally pass the muster carry with them an air of supremacy. Those who volunteer, both direct recruits and the lateral inductees, are required to go through a punishing probation period to test their skills. It is this distillation process that ensures that out of the 10,000 soldiers who wear maroon berets in a total army strength of 12,00,000 only around 3,000 pass through the grueling SF training that makes them special, physically as well as intellectually. However, even the remaining soldiers who sport maroon berets are better trained than the regular soldiers. This was more than evident in the prestigious 2002-2003 Defence Services Staff College examination, which grooms young officers for higher command, where 16 officers from the para SF regiment as against 106 officers from the Infantry made it to the final list. The para SF regiment has a total of 10 battalions as against 349 Infantry battalions. At present, there are a total of three Lt. Generals and nearly 10 Maj. Generals rank officers in the army who wear maroon berets. Such para SF regiment standards are possible because unlike the regular army, all para SF soldiers are volunteers. For example, an SF officer and even a jawan can, at any stage of his career, render a non-para volunteer certificate and revert to his original Infantry regiment. Conversely, a para SF commanding officer could declare an SF soldier unfit for the organisation and send him back to his Infantry regiment. According to directives from the Army Headquarters, such cases are not held against an individual’s performance as a regular soldier.

The training is accompanied by negative motivation. Laughs Col. Shinde, ‘I keep telling the men that why are you slogging like this. Sometimes, I tell them that they will never be able to complete the training.’ The idea is to toughen up the men mentally as well as physically

As of now, the volunteers go through the probation at their respective battalions where they get hands-on training in SF basic skills including signals and so on. For specific courses, such as para basics and combat free fall they go to Agra and for underwater diving they train with the navy at INS Venduruthy in Cochin. A select few, at the discretion of the Commanding Officer (CO), come to the school for training in such skills as weapons training, communication and emergency medical aid called Battle Field Medical Assistance (BFMA). Such a training schedule has continued since the formation of para commando units, much before the SF came into being. With only three para commando units, 1 para commando, 9 para commando and 10 para commando, the need was for specialised hard hitting units which understood the peculiarity of the area of its operations as they were supposed to be trained for different terrain. For example, 10 para commando was tasked for desert operations only.

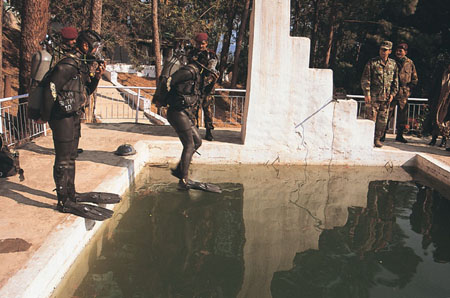

Following the basic training, a select SF personnel come to the school for advanced training, which to put it simply is backbreaking. Says Col. Shinde, “We give such intense training that it changes the biological clock of the volunteers. During the training there are no fixed hours for anything for an SF soldier.” The advanced training is divided into five capsules. The Special Skills capsule includes underwater diving, where an SF soldier is trained to go 10m or more underwater wearing either an air set or a close circuit set (it does not emit breath bubbles, hence does not give away the position of the diver). His training tasks include planting an explosive device and searching for targets. Combat free fall requires the trainee to jump with a bag of 30 to 40kg of equipment and glide nearly 10 to 20km inside enemy territory. “For an adventure para jumper, the task ends after touch down, but in combat it only begins once you land,” remarks Col. Shinde. The third part of the Special Skills capsule is surveillance and targeting.

The second capsule is Advanced Trade Training which is sub-divided into four courses: advanced demolition and sabotage, advanced medicine, advanced communication and information technology and advanced weaponry. The school runs a centre where volunteers are trained in manufacturing and using Improvised Explosive Devices (IED). The trainees are encouraged to come up with ideas for placing IED at unsuspecting places. Some come up with such innovations as a whiskey bottle, a waste paper bin apart from the more common ones as transistors, dolls and books. Those who are trained in advanced medicine are taught, apart from the basic health and fitness lessons, to treat broken bones, excessive bleeding, wounds, including suturing, and giving intravenous help.

Combat Techniques is the third capsule that includes training in combat leadership. “There is a lot of emphasis on firing skills. I can make out from the way a man holds his weapon as to how comfortably he can fire it,” says Col. Shinde. In combatshooting, the soldiers are taught to be so confident of their firing skill that they should be able to hit the target even if there are others in the line of fire. For this, the instructors stand next to the target as the trainee fire, so that the trainee understands that his instructor trusts him. The school has also built a mud structure, called Kill House, to train SF in hostage situations. The house is deliberately kept dark so that somebody coming from outside gets momentarily blinded, but despite that he has to be alert to shoot at the terrorist without hurting the hostages. The structure also has a raised platform for the instructor to watch the trainee practice.

The final capsule is more for recreational purposes and involves such aqua adventure activities as scuba diving. The trainees are also taught tactics such as Small Team Insertion and Extrication (STIE) operations, which means dropping the team behind enemy lines by a helicopter and picking them up after the completion of the task. Interestingly, all this training is accompanied by negative motivation. Laughs Col. Shinde, “I keep telling the men that why are you slogging like this. Go back to your battalion and have a good time. Sometimes, I tell them that they will never be able to complete the training.” The idea is that the SF volunteers are toughened up not just physically but mentally as well.

Since the upgradation of the wing in January 2003, all this is set to change. Not only has the school been given the status of Category-A establishment, its financial allocations are also likely to go up. Besides, with the army raising more SF battalions, there is a need for synchronised training. Hence, starting 1 January 2004, all para SF would do their probation and training at the school. The idea being that there has to be some amount of compatibility in training as the tasks before the SF will no longer be region or theatre specific.

Starting 1 January 2004, the SF volunteers would arrive at the school for a fivemonth probation period. In the first two months the volunteers would undergo a series of tests, which will evaluate his physical and psychological abilities. He will also be put through a drill to see his aptitude in various SF skills, such as, emergency medical aid, weaponry, communications, navigation and demolition. Following this, he will undergo a three months training in all the five SF skills. Once the probation is over, the volunteers will go back to their respective units for hands-on training and for various all-purpose basic courses. A select few will come back to the school for advanced courses in select skills depending upon their aptitude. Given that SF usually work in squads (five people), it has to function as a complete unit without any support system. Hence, in each squad one person has to be a specialist in one particular area, be it medicine, weapons, communications, navigation or demolition.

The New Face of War

The changing training schedule at the Special Forces Training School is the result of the new thinking within the Army which is set to change the face of war with Pakistan. Lessons of Operations Vijay (the 1999 Kargil war with Pakistan) and Parakram (the 10-month-long stand-off with Pakistan) had spurred the Army leadership to review the nature of war with Pakistan. After the Kargil war, both the defence minister, George Fernandes and the then army chief, General V.P. Malik had spoken of a possibility of a limited conventional war with Pakistan. The limitations were on space and time and hence on the military aims and political objectives as well. It was argued that in a nuclearized scenario between India and Pakistan there was a window available for a local conventional war. However, Operation Parakram changed this hypothesis. The army’s hope to fight a limited war in Jammu and Kashmir in January 2002 did not materialise. Therefore, to retain the element of surprise, by May, the army’s strategy had moved beyond a limited war to an all out conventional war. It was reasoned that destruction of Pakistan’s offensive forces would be both a desirable and achievable military aim. The army leadership was confident that decimation of Pakistan’s offensive prowess would keep the war within Islamabad’s nuclear threshold. India’s political leadership, however, did not agree with the military’s thinking. By not going to war after completely mobilizing the army, the latter’s capabilities have been blunted for a long time. The option of a conventional war with Pakistan has closed.

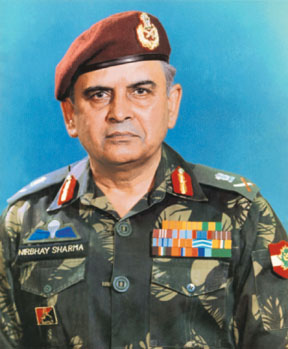

Colonel of the Parachute Regiment

For this reason, on taking charge of the army, General N.C. Vij, who had played a central role in both the operations, decided on two things. The army’s focus shifted inwards: from a conventional war with Pakistan to defeating the proxy war unleashed by Pakistan in Jammu and Kashmir. This is to be achieved by a two-prong action; checking the infiltration from the Line of Control, and by vigorous Counter-Terrorism (CT) operations within the border state. The army chief, General Vij recently told the FORCE’s consulting editor, Lt. General V.K. Sood, that, “The infiltration across the LoC is down by 30 per cent, and I am confident that it will come down by 90 per cent by end-2004.”

Simultaneously, the army chief ordered a review of the Special Forces in totality. With the conventional war option closed for the foreseeable future, the army believes that an employment of Special Forces in enemy territory will be the new face of war. A defensive campaign in Jammu and Kashmir in the form of CT operations by itself is insufficient. It must be backed by an offensive option which the SF allows.

Without confirming that this indeed is the new army thinking, the Colonel of the Parachute regiment, Lt. General Nirbhay Sharma, who is also the 15 corps commander in Srinagar says, “We have to be prepared for the changing face of war. Therefore, we have not committed our total lot in CT operations. We are keeping our powder dry.” The new army option implies that all aspects of SF, including its roles and missions, strength, organisation, equipment, man-management and training be dwelled upon. And this is precisely what is happening at the Army Headquarters and the Army Training Command in Shimla. The SFTS awaits new instructions.

Talking about the basics of this elite force, Lt. General Sharma says, “a paratrooper must have five characteristics: He should be trained for all climatic conditions; be able to operate in all terrains; be able to operate behind enemy lines; be adept at various modes of insertion into enemy territory; and be able to hold ground or carry out the assigned task by hit and run. Having accomplished all this, where he should be used, whether in our own territory or the other side, is a matter of operational necessity.” The general’s observation underscored three issues. He was talking about the Para regiment as a whole, which includes the para and the para SF battalions; he appeared to emphasise on the SF missions in enemy territory; and he did not rule out CT operations for the SF.

There is a school of thought within the army that believes that SF should not be employed on CT tasks. It is argued that SF are special forces and should not be used like regular forces, as commandos or on CT operations, as it is both a bad and an under-utilisation of the force. The urge to employ the SF as commandos came to the fore during Operation Vijay. The army leadership was completely surprised by the Pakistani forces ingress and occupation of Indian territory across the LoC in the Kargil sector. Unfortunately, the bulk of the regular army was tasked in Counter- Insurgency role and did not have the stamina to evict the intruders from snow-clad heights. In order to minimize own casualties, the army employed eight out of the 10 para and para (SF) battalions in what were essentially regular infantry tasks. The maroon berets did not disappoint. The 50 para brigade was used to clear the Mushkoh intrusions, while 5 para was actively involved in the Batalik sector. Like other para and para SF units, 9 para SF did a commendable job in the Dras-Mushkoh sector. Except for 10 para SF which has exclusive roles and missions in the desert sector, all other para SF battalions have done tenures in Jammu and Kashmir.

‘We have to be prepared for the changing face of war. We have not committed our total lot in CT operations. We are keeping our powder dry,’ says Lt General Nirbhay Sharma, adding, ‘CT operations provide an ideal training ground. It is giving the boys combat experience’

The SF have also been employed on CT tasks to the hilt in the border state. With three Ashok Chakras, the highest gallantry award during peace-time, 9 para SF was awarded the singular honour of being the ‘Bravest of the Brave’ by the Chief of Army Staff in 2001. Captain Arun Jasrotia of 9 para SF died in the Lolab Valley on 15 September 1995, while Major Sudhir Walia of the same unit, who had survived the Kargil war went down fighting terrorists on 29 August 1999 in Kupwara. And, the young paratrooper Sanjoy Chettri laid down his life combating terrorists in the Hill Kaka region on 22 April 2003. While there is regret in these units for having lost their special soldiers, there is also a sense of pride for having killed terrorists with minimum casualties to themselves. Few within the army wonder if the para SF were indeed doing the job they were meant to do exclusively. “The para SF have been involved so much in CT operations that they themselves have started believing that this is their major task,” observes a young para SF major at the SFTS.

Unlike a commando, an SF soldier is required to conduct clandestine, covert and overt operations. A clandestine operation is one which attempts to conceal its very existence, while a covert operation attempts to conceal its true authorship. An overt operation, on the other hand, does not attempt to conceal either the action or its perpetrators. Moreover, as many tasks of an SF soldier would be stand-alone and in enemy territory, it is necessary that he have a better and broader understanding of the war than a commando. It is, therefore obvious that these SF operations require that the SF function in smaller teams than the para commandos. This has led to a review of the para SF battalion organisation. Unlike the earlier para commando unit where the smallest grouping for operation tasking was a sub-team, the SF battalion’s smallest unit is a squad comprising five skilled soldiers. In addition to basic SF skills, the five soldiers have between them expertise in the field of medicine, weapons, navigation, communications and demolitions. This implies that a squad is self-contained to survive, operate and take appropriate decisions on its own when operating in enemy territory. The second higher denomination of soldiers in an SF battalion is a troop comprising 20 to 25 men, followed by a team which has about 90 soldiers. Unlike an Infantry battalion which has about 860 soldiers, an SF battalion is leaner with a total strength of 550 soldiers divided into four teams and a headquarters.

Notwithstanding all this, the army leadership found it difficult to grasp that even as an SF soldier has a commando in him, he should be employed differently from a commando. While an SF soldier should be employed minimum as a squad, commandos can be employed in large numbers, as well as in twos, on say, Counter-Terrorism (CT) tasks within own territory. Called the ‘buddy system’, which is typical to the commandos, two soldiers, irrespective of their rank, work in peace time and during operations as each other’s alter-ego. This facilitates assisting one another, as well as calling for help should one get trapped. On the other hand, it is difficult to comprehend tasks where an SF soldier would need a buddy in enemy territory. Even when an SF operates in squads, each SF soldier is self-contained and, more importantly, is capable of taking independent decisions. This trait distinguishes an SF soldier from a commando or a regular soldier. While the latter needs training in discipline, the former needs training in selfdiscipline. However, over the years the army leadership didn’t want to distinguish between the two.

Worse, the relentless pressure of CT operations in Jammu and Kashmir led to even the para regiment contributing towards the Rashtriya Rifles (RR), a task meant for normal infantry soldiers. The 31 RR has the commanding officer, the second- in-command and up to three to four officers from the para regiment, while the jawans of this unit come from the paratroopers, the Dogra and the Jammu and Kashmir Light Infantry regiments. Being a deputationist posting, the maroon berets stay in the 31 RR for two years before reverting to their parent unit. Even while doing the task of regular soldiers the paratroopers are required to go back to the Para school in Agra to do their mandatory annual jumps.

‘The para Special Forces have been involved so much in Counter Terrorism operations that they themselves have started believing that this is their major task,’ observes a young para SF major at the Special Forces Training School

As a result, an SF soldier has been allocated onerous roles and missions which are meant for the Special Operation Forces, commandos and regular Infantry combined. Probably, this explains why the Indian Army has SF soldiers and not SOF soldiers like the US Army. An SF soldier is simply special or elitist, but could be tasked on a variety of missions including those meant for the regular army and commando units. An SOF, on the other hand, is utilised only for Special Operations (see box). Senior para officers are not ruffled by such a criticism, and are eager to explain why SF is employed on multitude tasks. According to Lt. Col. J.S. Nanda, a para SF officer who was injured in CT operations where he lost his buddy, “Unlike the US which has a Special Forces Command where different SF entities are used on special tasks alone, we have a limited strength of SF. This makes their employment on a variety of roles inescapable.” Agreeing with his officer, Lt General Nirbhay Sharma adds, “CT operations provide an ideal training ground. It is giving the boys combat experience.” The general feels that comparisons with the US forces are unnecessary, as with limited resources, the SF have improvised a lot of things. For example, each SF soldier carries a sanitary napkin instead of a bandage roll after it was realised that the napkin was a better absorbent of blood.

Notwithstanding what senior para officers say openly, they realise that the SF are indeed special and should be used sparingly on tasks within own territory. The army, after Operation Vijay, has created a Ghatak platoon (commando platoon with about 20 soldiers) for each Infantry battalion on the LoC. It was realised that if Infantry battalions have their own Ghataks, the need for employing the para SF on commando tasks for a conventional war would be avoided. Simultaneously, there has been a need to provide better equipment, and rest and relief to the Rashtriya Rifles (RR) on CT role. These twin requirements led to placing the Infantry Modification 4B model on a fast track for government approval. Infantry Modification 4B provides the Infantry units with better, lighter and accurate firepower permanently. For example, Infantry battalions would be equipped with Anti-Material Rifles, Under Barrel Grenade Launchers, 12 bore Pump Action Shot Guns, Sniper Rifles (from Israel) with night vision devices and so on. The army has proposed that both Infantry battalions and RR units be placed on Modification 4B. To make sure that regular troops can operate comfortably in inclement weather, the Army has decided to first procure the necessary quantity of high altitude area clothing and equipment for Ghatak platoons of units in high altitude and glacier areas. Once accomplished, this would provide tremendous relief to the RR and also diminish the urge to employ the para SF on commando tasks on the LoC and in CT operations to assist the RR.

On the question of an increased use of SF in enemy territory, Lt. General Sharma was evasive. “I do not think anyone will discuss SF roles and missions in the media,” he said. However, there are officers who are willing to do so as background briefing. Says one officer at the SFTS, “While a troop of para SF could be employed for conducting raids and focussed destruction of enemy’s military targets, a squad can be used for surveillance, sniper shots, Laser Target Designation and so on.” Some of the other SF roles could be trans-border and LoC patrolling including crossing of rivers forming part of the latter; raids on training camps to either destroy them or capture important leaders; reconnaissance of water obstacles to find possible ferrying sites for vehicles of different kinds; guiding friendly aircraft to targets, such as militant’s training camps, headquarters, communication centres and so on; designating targets for them; and conducting vehicle mounted reconnaissance by air (helicopters) and exfiltration on wheels. “What needs to be understood is that SF could be used on a wide spectrum of missions with intelligence gathering on one end and combat operations on the other. Even as the situation would dictate their employment, care needs to be taken to use SF inenemy territory only,” observes a General Officer Commanding who is heading a Rashtriya Rifles Forces Headquarters in Jammu and Kashmir.

Even as the army leadership has been mulling over the nature of future operations and an increased employment of the para SF in enemy territory, increased army co-operation with the US introduced the SF to a range of new equipment with their Special Operations Forces (SOF). The army to army co-operation between the two countries has essentially been between the Special Forces. For example, during exercise Balance Iroquois 2003-01, a Joint Combined Exchange Training, the Indian Army’s 21 para SF lived, worked and trained with the US SOF at the Counter Insurgency Jungle Warfare School in Mizoram. Says Colonel Steven B. Sboto, US defence advisor in New Delhi, “The training activities ranged from advanced marksmanship and various infiltration/exfiltration techniques to jungle survival and counter-insurgency techniques. Principal training scenarios included cross-country movement in jungle terrain, operations in rural and semi-urban terrain, and operations against a defended enemy base camp. During any of these activities, Indian and the US soldiers shared equipment, such as night vision goggles, rifles, and jungle boots, providing opportunities to evaluate each other’s field gear.” The Indian para SF tested most of the equipment with the US SOF during these exercises, and showed an interest to procure some of them. The moot thing about this equipment is that it is meant for operations in hostile territory. It, therefore, appears that procurement of specialised SOF equipment will further spur the army to find new roles and missions for the para SF.

Meanwhile, with the expansion of the para SF, the oft asked question of whether the para and para SF should be separated has re-surfaced. To understand this, there is a need to take a look at the Para regiment (SF). The Para regiment (Special Forces) comprising the 50 independent parachute (Para) brigade and para (SF) stands at the fourth and probably the most critical milestone in its post-Independence existence. The first milestone was the raising of the para regiment on 15 April 1952. On this day, three battalions serving with the 50 para brigade were taken away from their parent Infantry regiments to form the para regiment. The battalions were 1 para (Punjab), 2 para (Maratha) and 3 para (Kumaon). The second milestone was after the 1965 war with Pakistan when the latter employed its irregular and Special Services Group (Special Forces) during Operation Gibraltar in Jammu and Kashmir. In a clever plan, Pakistan launched its covert operation in Jammu and Kashmir on 8 August 1965, weeks before it declared a conventional war by Operation Grand Slam on September 1 in Chhamb. The Indian Army hurriedly culled together a commando force of volunteers, called Meghdoot, from various units to meet the Pakistani challenge. After the war, the para regiment was given the job to raise a unit of speciallytrained personnel for commando tasks. This resulted in the formation of the army’s first commando unit, the 9 para commando at Gwalior on 1 July 1966. The 10 para commando was also raised at Gwalior on 1 June 1967, while 1 para commando was raised in 1979 at Agra.

Late General B.C. Joshi is credited with the third milestone in the life of the Para regiment. Learning the lessons from the first Gulf War against Iraq where the US employed its Special Operation Forces (SOF) with success, the army decided to convert the three para commando battalions into para SF battalions. A moderate amount of specialised equipment was procured from abroad and the Special Forces Training Wing was establised at Nahan in Himachal Pradesh in 1993. A year later in November, all three para commando battalions were re-named as para SF battalions. However, according to Lt. General Sharma, “renaming the para commando as para SF was really a matter of semantics. Both the terms, commando and SF are foreign in origin. So when some officers did courses abroad, they changed the term commando to SF.”

In terms of the organisation, by November 1999, the para regiment (SF) had a total of 10,000 soldiers comprising five battalions each of the para and para SF units. In addition, the para regiment has the President’s Body Guards, the 9 and 17 Parachute Field regiments, the 411 and the erstwhile 410 Parachute Field companies of the sappers, the 50 independent Parachute Brigade Signals company, elements of the 12 and 13 Mechanised Infantry, the 622 Parachute company of the Army Services Corps, the 60 Parachute Field Ambulance, the 50 Independent Parachute Brigade Ordnance field park, portion of 31 RR, and the 50 Parachute Brigade Provost unit.

Lt. General Sharma asserts that para and para SF are inseparable. Many other officers think otherwise. They feel that the insignia ‘Balidan’ which denoted the para SF should be divorced from ‘Shatrujeet’ which represented the para battalions. It was argued with merit that the para SF has different roles and missions from the para battalions, which has led to different organisations and tactics. For example, a para SF operation never envisages holding of ground, whereas a para operation may require capture and temporary holding of ground till the regular force links up and takes over. During the 1971 war with Pakistan, 2 para battalion group was paradropped at Tangail, then in East Pakistan, which contributed substantially to the hastening of the creation of Bangladesh. Similarly, three para battalions under 50 independent para brigade took part in Operation Cactus in 1988, (which implied a temporary holding of ground), the first successful operation in aid of the duly elected government of Maldives. It was reasoned that the only thing which binds the two sister organisations was their basic parachuting skills. However, the main argument which worked against this division was to have separate Para regimental centres for forces with strength of five battalions each. The para regimental centre provides bulk of the paratroopers and after having moved five times since its inception, is now settled in Bangalore since 15 January 1992. For troops, the regimental centre is the alma mater, where they first come to join the regiment, and pay the last visit before hanging uniform on retirement.

According to Lt. General Sharma, the recent decision whereby all paratroopers are volunteers has helped man-management in the regiment. Till recently, only the officers were volunteers while the rank and file stayed permanently in the regiment. Now all para and para SF soldiers are on probation for five years during which they can be sent to their parent Infantry regiment. The other issue which has been taken up with the government is the special pay and allowances for the para SF soldiers. As against a Marine commando (Marcos) officer who gets an additional allowance of Rs 7,200 per month, and the Air Force flying bounty which is Rs 7,000 per month, a para SF officer gets a measly amount of Rs 2,200 each month. This is a sore issue and rattles the para SF officers. Even as things are steadily improving in the Parachute regiment, the truth is that the army can only employ this special force in a narrow sense. All suggested roles and missions for the para SF are either tactical or operational in nature. Considering that the traditional battlefield has increased in depth, the separating line between tactical and operational depth has blurred. The Army, after all, would use its forces, for tasks which it would be required to do in war. For this reason alone, there is little interaction between the para SF and the Indian navy’s Marcos. So much so, that neither are clear about the other’s strengths, weaknesses and taskings. Says a senior para SF officer, “They operate in the sea through their ships and submarines. We (para SF) operate in inland water bodies like lakes and dams.” The US, however, feels that it is important to understand the Marcos as much as it desires to know the para SF better. According to top defence sources, the US SEALS and Marcos are in an advanced stage of planning joint exercises on the west coast, preferably in Goa or Mangalore.

The Marcos, which came into being in 1987, have a strength of 700 commandos (which they hope to increase to 1,500 by 2008), and do their basic training at INS Abhimanyu near Mumbai on an island. Marcos are divided into a squadron each for the Eastern and Western coasts. Modelled on the US Navy SEALS, Marcos were raised to fulfil the need for an elite force for special maritime operations. They have seen action in Operation Pawan in Sri Lanka and Operation Cactus in Maldives in 1987-88. At present, the Marcos play a role in the CT operations in Jammu and Kashmir. They are tasked to check infiltration of terrorists from Pakistan through the Jhelum River and the Wullar Lake in Srinagar. Marcos’s operational tasks would include laying and clearing of limpet mines, carrying out offensive action behind enemy lines, swim under water for nearly one mile and also be dropped by submarines in enemy waters. Marcos operate as platoons (called prahars), and as sections of 8 men team (equivalent to a para SF squad). The navy has procured midget training submersible small boats from Italy for the Marcos. It has also purchased a small quantity of Israeli Nagev Light Machine Gun for its commandos. The navy, understandably like the army, can only formulate tactical and operational tasks for Marcos. Unlike the other two services, the Indian Air Force does not have any special or commando force. Therefore, unlike the US SOF, there is no strategic utilisation of Special Forces. Even if the government was to use the army para SF on strategic tasking, it would require elaborate planning at a level higher than the chief of army staff. This would necessarily be the job of the National Security Advisor or better still, the Chief of Defence Staff, if and when it is formed. This, however, does not bother the army which is determined to change the nature of war to its advantage.

Also Read:

Army to Raise Additional Five Battalions of Para SF

The Army plans to raise an additional five battalions of para Special Forces (SF) by the end of the 10th Army plan (2002 to 2007). The conversion of two para battalions into SF (4 para followed by 3 para) will be completed by 2005. Expected allocation will be two para SF battalions each to formations actively engaged in CT operations and deployed in high altitude areas.

Also Read:

The XYZ of Special Operations

Searching for an Indian Role for Special Operations Forces (SOF)

Also Read:

Weapons of Choice

Even as the new equipment for the para SF is meant to replace the existing vintage lot the bulk of it is for operations in hostile territory.

Also Read:

US Special Operations Forces

Special operations forces are playing a key role in the Iraq conflict, albeit a covert one given the secretive nature of these units.

It works very well for me