Into the Future

In keeping with our wanderlust, in January 2004, FORCE team visited the BSF Academy at Tekanpur to get a first-hand account of India’s leading border guarding force. The visit was the curtain raiser to the larger article on India’s paramilitary forces. Since then, FORCE has paid as much attention to internal security, as it did to external defence. Read on

With changing roles, Indian paramilitary forces embark on a modernisation trail

Pravin Sawhney and Ghazala Wahab

There are no whispering spirits at the Border Security Forces’ Academy in Tekanpur. Their presence would have made it a perfect getaway for romantics. Despite a boring though apt name, the BSF calls it Suraksha Bhawan, the headquarters of the academy, overlooking a lake steeped in romance, enhanced by legends, gossips and fantastic real stories. Once upon a time, (there is no other way to say this) Suraksha Bhawan was the house of adventure and erotica, perhaps to do with its proximity to Khajuraho. In 1938, Maharaja Jiwaji Rao Scindia of Gwalior built a retreat in the form of an anchored ship complete with multi-layered decks as a romantic getaway on the bank of the lake, Band Tal ostensibly for his beloved. Surrounded by lush forests, which at one time boasted of tigers and leopards, the retreat also became a rest house for the king’s European friends who would frequent the place for game. The story goes that the king used to ride his horse till the edge of the crocodile-infested lake and then take a boat to reach the retreat, where apparently his beloved waited for him. The section of the lake where the king used to leave his horse now houses the BSF’s equitation school. As no lore of love and adventure can be complete without dacoits or highwaymen, even this tale has its share of villains. The remote lushness of the retreat and the neighbouring places attracted the attention of the notorious dacoit Madho Singh, who terrorised the region for many years. The retreat remained dacoit-infested and desolate till Rajmata of Gwalior sold it to the BSF along with 52 acres of surrounding land in 1965. More land was procured subsequently from the Madhya Pradesh government.

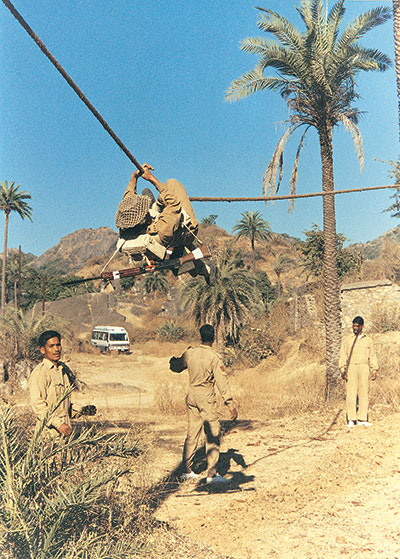

What once played host to dainty feet adorned with jingling anklets today reverberates with the heavy-duty leather boots of the BSF personnel. The retreat or the Suraksha Bhawan is the nuclei of the Academy sprawling over 2,923 acres of lush land including 643 acres of the lake area. Not only the freshly recruited BSF officers and men learn the ropes here, senior officers also come back for advanced courses before picking up their next rank. The academy, which was recently accorded the honour of being a Centre of Excellence by the deputy Prime Minister, Lal Krishna Advani, comprises a number of training centres, including the Special Training School where the freshly recruited young officers (Assistant Commandants) and Sub-Inspectors undergo basic skill courses. Apart from the BSF cadre, the academy also trains officers from other border guarding forces, such as, Indo-Tibetan Border Police and Special Services Bureau. Subsidiary Training Centre runs management courses for senior officers at the level of DIGs or commandants. The course module is developed by the Institute of Technology and Management (ITM) which combines the best of IITs and IIMs. While the Tactical Training Wing runs commando courses, the Artillery Training School, as the name suggests train the boys and men in the basic artillery skills. Then, of course, there is an equitation school to train horses, a dog school and a Central School for Motor Transport.

The hub of activity is the Special Training School which is headed by DIG R.K. Ponoth. The school runs two foundation training courses, a 55-week course for assistant commandants (that’s the direct entry level for officers, equivalent to a lieutenant in the army) and a 48-week course for Sub-Inspectors (direct entry level for men, equivalent to a Naib Subedar in the army). Apart from training the new recruits in attitude, aptitude and leadership, they are also initiated to modern weaponry. Given that the BSF’s primary job is border management and they need to be in constant touch with border population, such subjects as human rights and law form an integral part of the training. Says R.K. Ponoth, “We run a two-day human rights capsule devised by the International Committee of the Red Cross. The essence of border management lies in the minimal use of force. And that is possible if you win the trust of border people. Hence, it is important that our men understand the nuances of law and human rights.” Since the recruits are also taught to live off the land they go through a commando schedule where they are expected to survive on snakes, scorpions and other worms.

After the recruits complete the basic skill course that comprises physical education, drills, weapons training, field craft, map reading, police subjects, equestrian training, border management, tactical training, law and the simulation of counter- insurgency scenario they go back to their respective units for on the ground attachment to the army for two months, as in many areas, like other para-military forces, the BSF works under the operational control of the army. The Academy also runs a five-week anti-fidayeen course, which according to the DG, BSF, Ajai Raj Sharma, has been devised by him. The course enables the trainees to learn laying ambush and to function as quick reaction teams.

“This is a 100 per cent BSF special. We have taken no assistance from the army for this,” says Sharma. Subsequently, senior officers come back to Tekanpur for refreshers training. “In BSF, all officers and men have to complete a few mandatory courses and put in a mandatory service in the field before they become eligible for the next rank,” says Ponoth.

For specialised training, such as water patrolling, desert patrolling, counterinsurgency operations, advanced weaponry and tactics, they go to their schools in Gujarat, Rajasthan, Hazaribagh and Indore respectively. The Central School of Weaponry and Tactics (CSWT) at Indore boasts of a world class shooting range, which can also be used for international sporting events. The shooting range owes itself to the commandant, CSWT, DIG Mohinder Lal, an Arjuna award winner and a world class shooter himself. “We maintain a close professional interaction with the army training establishment, the Infantry School and the College of Combat, in MHOW,” says DIG Mohinder Lal.

The BSF prides itself on the fact that it is one of the most modern and technologically savvy para-military forces in the country. Everyone is computer-literate and all officers at the academy carry their own laptops. Yet, the strength of the BSF lies in its training which ensures that while the force retains its policing element in spirit, in all the other aspects it remains a military force. As the face of the war changes, the BSF, like other paramilitary forces, has embarked upon a long march towards modernisation.

On The Vigil

“The government has cleared the deputation of an Air Vice Marshal from the Indian Air Force to head the air wing of the BSF,” says a visibly pleased DG Sharma. “The force,” he adds, “had acquired six Mi-17 helicopters from Russia in November 2003, and there are plans to acquire two 50- seater executive jets, more Avros, Cheetah and Chetak helicopters.” All these air assets “are needed to provide logistics to the 34 Border Out Posts (BOPs) in the North East which are completely maintained by air.” Until these new acquisitions, the BSF airwing had two Super King Air, three Avros and two Chetak helicopters. The helicopters are located one each in Srinagar and Jodhpur, while the other air assets are in Delhi. The Avros are being used to transport arms, ammunition and equipment, and the helicopter in Jodhpur is employed for aerial patrols.

In addition to the air wing, the water wing of the BSF has been sanctioned 14 medium crafts, 25 mechanised boats, 131 speed boats, 61 country boats fitted with engines, 141 country boats and 120 Naka boats. To match Pakistan’s Marine Security Agency, the counterpart of the Coast Guard, the BSF has proposed adding six hovercrafts, swamp boats, one interceptor boat, GPS and Echo Sound System, and four gun boats. The BSF was also sanctioned nine floating BOPs in 2002. A float- ing BOP operates in shallow waters and has four fast boats which can accommodate 40 fully armed men. This makes the floating BOP self-propelled and enables it to shift to any vantage point and patrol the surrounding areas with the help of boats attached to them. “The floating BOPs, one each in Sunderbans, Creek, and in Assam, are already operational while two more are expected to join the service soon,” says Sharma. The delay in procurement according to the BSF chief was “because of some differences which the Mazagon docks in Mumbai had with the contracted Australian firm which have now been sorted out.” The rapid modernisation of the BSF’s air and water wings and its artillery underscores the point that the BSF is re-orienting itself to its primary task of border management.

The BSF since its inception on 1 December 1965 has come a long way. The force owes its birth to the then Union home secretary, L.P. Singh, the army chief, General J.N. Chaudhuri and the first DG of the force, K.F. Rustamji, an officer of the erstwhile Indian Police. Raised under an act of Parliament as a Border Security Force for ensuring the security of borders of India, the BSF was formed by an amalgamation of 25 battalions of existing state armed police. Today, with 157 battalions, the BSF is the largest paramilitary force in the world. At the time of its birth, it had all deputationist officers from the army. And its single task then was to hold out against an enemy for a short duration, thereby gaining some time for the army to deploy and respond effectively. However, all this changed over time. Today the BSF has its own cadre of officers. Yet, the top two posts of DG and Additional DG, 67 per cent of total posts of Inspector Generals, and 60 per cent of Deputy IG posts are held by Indian Police Service officers. The army contributes just seven per cent of total DIG posts (the second-in-command at the BSF Academy at Tekanpur, who is in charge of the training, is a retired brigadier from the army). Even as the top leadership of the force now has a police orientation, the tasks of the force, accordingly, have also changed a lot. Just about 33 per cent of the force remains on its primary task of border management. The rest is involved in Counter-Terrorism operations, mainly in Jammu and Kashmir. Like the Rashtriya Rifles, which is regular army by another name, the BSF has excelled itself in CT operations in Jammu and Kashmir. “We loose up to 100 men each month to CT operations and to inhuman and difficult living conditions in the North East, where snakebites and cerebral malaria are commonplace,” says Ajai Raj Sharma.

Even as there is an added emphasis on counter-terrorism training in the BSF establishments to cope with well-armed, trained, equipped and hardened foreign terrorists, the fact is that the BSF has veered away from its basic task. “BSF is army in khaki, just as the CRPF is a police force,” says DIG, SID Peter who has done enough CT operations in the Valley. There are cadre officers like DIG Peter who know that the BSF should not do policing duties but return to its job for which it was raised. It is another matter that the BSF’s primary task itself has undergone a metamorphosis: from being the first line of defence to border management. This is in tune with the changed realities where the dividing line between peace-time situation and low-intensity-conflict has blurred. There are more challenging trans-border crimes, unauthorised entry into or exit from the territory of India, smuggling and illegal activities than were ever before. Moreover, terrorists infiltrating in Jammu and Kashmir are equipped with state-of-the-art equipment and communications systems. All this requires effective and regular border management with skills and equipment which beats those of the intruders.

As far as war is concerned, once it is evident that an all-out-war is inescapable, there will be few ‘less threatened’ areas and few ‘sudden attacks.’ Deep surveillance means, rapid mobilisation drills, long range air and land-based firepower, and the nuclear backdrop will ensure that there will be few operational surprises, and the first 72 hours of the conventional war would be fierce, swift and devastating. Once the war balloon goes up, the BSF’s role will immediately switch over to supplement the regular army, assisting in the maintenance of war logistics lines and guarding vulnerable areas and points.

The BSF, therefore, has unenviable tasks. During peace, it is border management, which requires good policing and military skills. During war, the BSF soldiers should stand as tall as the regular army itself. The BSF can accomplish such tasks only when it is relieved of CT operations. This is what the task force on ‘Border Management’, constituted by the government after the 1999 Kargil war suggested which led to the Group of Ministers (GoM) recommendations endorsing the same. The two main recommendations of the GoM report are: one border, one force; and a need to strengthen intelligence. The difference between the task force on border management and the GoM reports is that while the first is an unreleased comprehensive document suggesting steps to be taken to make border management effective, the latter’s recommendations were released by the deputy Prime Minister, L.K. Advani. For obvious reasons, the GoM report is vague on details. For example, the Border Management report has said that only the BSF, the Indo-Tibetan Border Police force and the Assam Rifles are the Border Guarding Forces and should be designated as Central Para Military Forces (CPMF). All other forces under the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) such as the Central Reserve Police Force and the National Security Guard amongst others should be known as Central Police Organisations. Moreover, the CPMF should either be completely under the Ministry of Defence (MoD) or the MHA.

The BSF is responsible for guarding the borders with Pakistan and Bangladesh which is done through its BOPs. The strength of a BOP varies between a platoon to a company depending upon operational requirements. As a rough rule a battalion can have up to 18 BOPs. At present, of the total 157 BSF battalions as many as 59 battalions are on CT operations. This has led to a thinning of BOP strength, long working hours for men, and, in too many cases, to an unacceptable inter-BOP distance. It has been estimated that to be effective, the inter-BOP distance should not be more than 3.5km. Barring Jammu and to some extent Punjab, this gap is well over 4km. On Tripura, Cachar and Mizoram frontier, it is as high as 7km.

The International Border (IB) with Pakistan covers a length of 2,300km spread over the states of Jammu and Kashmir, Punjab, Gujarat and Rajasthan. There is a 220km IB in Jammu and Kathua districts of J&K which Pakistan calls the ‘working boundary.’ Of the 220km, 10.5km are guarded by the army. In this stretch, the BSF has been deployed under the operational control of the army. Rest of the IB here is guarded by the BSF. In all, 12 BSF battalions have been deployed on this border, five on the Line of Control and seven on the IB as against the sanctioned 18 battalions. The Punjab border, on the other hand, is 554km-long including 152km of riverine tract along the Ravi and Sutlej rivers. 500km of this border has been fenced. This border has 169 BOPs and 266 gates which are manned by BSF personnel to regulate the passage of local people for cultivating the land between the fence and the zero line. Out of the 24 sanctioned battalions for this border, only 14 are actually deployed. In the 1,037km-long Rajasthan sector, of the total sanctioned 24 battalions, only eight battalions are deployed, the remaining are on CT duties in J&K. The 498km Gujarat border includes 99km of the Creek area and is an extremely difficult border which is guarded by an inadequate water wing. The latter is in dire need of modernisation and training facilities to regularly upgrade the skills of those manning the water wing.

It is clear that guarding the border with Pakistan provides a host of challenges for the BSF. For instance, the Punjab border is extremely vulnerable to smuggling. Moreover, the security and checking arrangements at the Attari station, and the Wagah check post through which the buses between India and Pakistan ply require attention. Then there are increasing signs of infiltration of terrorists, traffic in arms and drugs in the Rajasthan border. Furthermore, living conditions are extremely harsh in many parts of the Rajasthan-Gujarat frontier, particularly the desert and the Rann. “Due to acute shortage, water is rationed for men in the desert. Hence, a jawan gets to have a bath only once in two days. Even this water is not wasted. After some rudimentary treatment it is stored for the camels to drink,” says DG Sharma. The BSF, in addition, does not rule out possibilities of Bangladeshi nationals being pushed out of Pakistan using the Gujarat route to enter India. “Border man agement means that BSF personnel has to be adept in many things ranging from surveillance, patrolling, Human Rights issues, law, checking infiltration, smuggling, migration, trans-border crimes, and dealing with border communities with compassion,” says DIG R.K. Ponoth.

Besides such complex and multifarious border guarding challenges, the BSF is also required to support the regular army in J&K. This implies that its weapons and training should not be inferior to regular infantry battalions. “We have purchased surveillance equipment including hand held thermal imagers, night vision devices and so on,” says DG Sharma. The BSF is replacing the 7.62mm rifles with the indigenous 5.56mm INSAS. It has 81mm mortars, and since the year 2000, it has acquired Carl Gustaf rocket launchers and anti-tank grenade launchers. The tenure of a BSF battalion on the border in J&K is two years.

The BSF is also responsible for the Bangladesh border. Besides other meetings, the DGs of the BSF and Bangladesh Rifles meet once a year to sort out mutual problems. According to Sharma, two issues crop up during all discussions: the illegal immigration of Bangladeshis into India, and terrorists camps on Bangladesh soil. An amused Sharma says that during the recent meeting held in December 2003, “The DG Bangladesh Rifles told me that many Indians were illegally migrating into Bangladesh, and that 39 camps on Indian soil were being used by terrorists for anti- Bangladesh activities.” Whatever be the truth, the fact remains the relations between the two paramilitary have nosedived in recent times.

Despite the successes that the BSF has notched in the last few years, the force remains mired in various inherent problems that stem from its organisational structure, ethos, recruitment policies and importantly faulty and overstretched taskings. For example, the government in 2000 decided to increase the strength of the BSF by adding an additional company to each battalion rather than raise new battalions. At present, a battalion has seven service companies and a support company instead of the earlier five service companies, one training company and a support company In this way, the BSF strength of 157 battalions has remained the same as it was in 1999. However, instead of 942 companies, the BSF today has a total of 1099 companies. Worse, the training company with each battalion has also been pressed into work as a service company. This was done by the government to save money needed to raise new battalions, but has resulted in many operational and command troubles and dipping morale. It is fine when BSF companies are employed as single units. But the additional service company without an increased infrastructure in a BSF battalion has meant tenuous central command and control, and a strain on limited resources of a battalion headquarters. Moreover, with more junior aspirant officers and no increase in vacancies of battalion commanders, promotion avenues for cadre officers have deteriorated. Worse, “The force had 22 reserve battalions at the time of raising to cater for rest, relief, collective training and annual change over. But since it no longer has reserve battalions, annual training is suffering,” says DG Sharma. Moreover, specific to J&K, the BSF faces the same hazards as the regular army in CT operations and on the Line of Control, yet there is a glaring disparity between the two services in terms of high altitude clothing, authorised personnel diet, and even compensation for disability and death, laments DG Sharma.

Yet another problem of the BSF is of its own creation. Based upon a former DG’s recommendation, the 5th Pay Commission abolished the rank of Lance Naik and Naik from the BSF, ITBP and Assam Rifles. The Lance Naik represents the lowest level of leadership and the entire leadership below the officer level is built through the ranks of L/NK, NK, SI and Inspector. By abolishing the two lowest ranks of the leadership ladder, the very basis of development of leadership at the operational and ground level has been thrown overboard. In the present dispensation, a constable has to wait for over 15 years for his next rank promotion. The lack of an adequate provision of leadership at the lower levels is a major shortcoming of the force. Moreover, the same Pay Commission has raised the age of retirement of all other ranks to 57years. This implies that even when a person is a low medical category, he cannot be superannuated early. It is understood that there are over 4,000 such persons in the BSF who cannot be employed on most outdoor duties. It is felt that continuation of employment beyond the age of 50 should depend upon an individual satisfying the standards of physical fitness and medical category.

Even while the BSF is like the regular military, it lacks regimentation, which is a sense of belonging to one’s regiment, one’s men, and even the unit’s property. Within the regular army, officers are commissioned into a unit, they return to it regularly after stints outside, are proud to command the same unit, and come back to it after retirement during reunions. This builds up the espirit-de-corps, and officers and men of a unit live and die for one another. This is missing in the BSF where an officer is commissioned into a battalion and then never comes back to it again. “All this will change as the BSF is working to bring regimentation in the service,” says Brig. Onkar Singh, the deputy director of the BSF Academy.

What, however, is unlikely to change is the complete domination of the top positions of the BSF and other paramilitary forces by IPS officers. Unlike the army where a young officer goes up the promotion ladder to become the chief, the top slots in paramilitary forces are held by IPS officers who come to command the force for two years. This has its own pros and cons. On the plus side, the IPS officers, unlike senior army officers, have enough exposure of the bureaucracy and political leaders. They are thus better placed to help the service formulate practical and achievable policies. Unfortunately, these officers have not seen the hard life of the force and rarely understand the cadre, which many times lead to framing of wrong policies. A case in point is the abolishing of the lower ranks in the paramilitary forces. Many officers within the BSF feel that as the service has matured, cadre officers should also have the opportunity to rise to the highest post.

This issue, however, is debatable as the recruitment procedure of officers in the BSF also needs to be reviewed. Unlike the army where bulk of officers joins the service at a very early age, officers in the BSF are recruited between the ages of 22 to 27years. “This means that before joining the BSF, the individuals have usually tried their options elsewhere, including the army in some cases,” says a DIG who did not want to be identified. Such individuals often lack the necessary spark, it is said. But then there is a difference between feeling and seeing. Probably the time has come to give the cadre officers a chance to head their force.

Sentinels of the Himalayas

They call themselves the Himveer, the brave hearts of the Himalayas. At any given point they operate at the heights ranging from 9000 to 18,000ft, often crossing passes at 21,000ft. They are not just soldiers, but mountaineers, skiers, rafters and martial arts experts. As the DG, ITBP R.C. Agarwal says, “The ITBP is the only paramilitary force that has an all India character and operates in high altitude areas on a long term basis.” However, the Himveers are getting more and more mired in the plains for jobs which weren’t theirs to begin with. DG Agarwal gives a long list of responsibilities that ITBP has been undertaking with success in the last few years. “The ITBP plays an important role in organising the Kailash Mansarovar Yatra since its inception in 1981. It is the nodal agency for both, training United Nations Civil Police officers and disaster management in the Central and Western Himalayan regions. Besides these, it provides Road Opening Parties (ROPs) and security in Jammu and Kashmir for the Jawahar tunnel, and the entire National Highway 1A which connects Jammu with the Valley,” he says, adding, “The force also guards select VVIPs and gives security to Indian missions in Sri Lanka and Afghanistan.” In addition to this, the ITBP runs National Disaster Management Centres, one each in Greater Noida and Chandigarh which trains ITBP and various other police forces in, among other things, Nuclear-Biological-Chemical war responses. “The force gives specialised training in commando and judo-karate. Nearly 100 Indian Air Force commandos (for its special forces organisation called Garud) have been trained by us,” says DG Agarwal. All the above tasks are done by the force with a total of mere 30 battalions (11 of which have been inducted in Jammu and Kashmir), including four specialist battalions in telecom, transport, area weapons, and service supplies. Like the BSF, the ITBP has added 38 companies to its existing battalions instead of raising new ones.

However, in this excitement, the point that the ITBP has a more delicate border guarding task to perform on the Line of Actual Control (LAC) with China than the BSF has on the borders with Pakistan and Bangladesh gets sidelined. Unlike the Line of Control with Pakistan in Jammu and Kashmir which is clearly delineated and is guarded by the regular army, the 4,056km LAC is neither delineated nor demarcated on the ground. Leave alone agreeing on how the LAC runs on ground, India and China have not even spelt out respective interpretations of the military held line. This makes the LAC prone to tactical changes by either side. And this is what China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has been doing since 1998, says the unreleased Border Management report. For example, the PLA has been doing aggressive patrolling up to and even inside Indian territory in Trig Heights and Pangong Tso in the western sector of LAC. This has resulted in new disputed pockets being formed both in the western and eastern sectors of LAC. The LAC runs through 832km in Ladakh region of J&K (western sector), 554km in Himachal and Uttaranchal states (middle sector), a 200km stretch of international border in Sikkim, and 1,126km in Arunachal Pradesh (eastern sector). The western and middle sectors are the responsibility of the ITBP, while Sikkim and the eastern sector are with the Army and the Assam Rifles.

Today, the biggest operational challenge for the ITBP is the implementation of the GoM report which says ‘one force, one border.’ The task force on ‘Border Management’ has recommended that the ITBP take over guarding duties on the entire border with China, implying that it replace the Assam Rifles battalions. The latter operates under the operational control of the Army with a battalion in Sikkim and four battalions in Arunachal Pradesh. Even as replacing the AR does not look a challenging task, the sticking point for the ITBP is the ‘operational control of the army’. “One battalion has already reached Sikkim and two battalions are being sent to Arunachal Pradesh. These battalions will familiarise with the area by first undertaking Internal Security duties before they do the border guarding tasks,” says Agarwal. On the question of whether ITBP, like the AR, will come under the operational control of the Army, Agarwal emphatically says, “We will prefer coordination between the ITBP and the army during peacetime. This has worked well in the western and middle sectors.”

However, the undisclosed ‘Border Management’ report which was prepared by experts chosen by the government does not think so. According to the report, ‘The PLA with better and fast growing infrastructure and aggressive patrolling has created more disputed areas in the western and eastern sectors. Under the guise of bet- ter border management, the PLA has enhanced the level of activity along the LAC in areas of Trig Heights, Pangong Tso and Demchok in Eastern Ladakh’. Unlike India, all Chinese border guarding forces are under the direct control of the PLA. On the Indian side, the ITBP deployment is based on platoon level posts on the LAC and controlled by respective company headquarters. The ITBP battalion and sector DIG headquarters have been relocated in such a manner that they are now able to exercise effective operational control. The army units which are located close to the ITBP posts have being doing joint patrolling since 1996 when the PLA heightened its activities in the western sector. The present arrangement of ‘functional coordination between the army and the ITBP seems to function adequately only during periods of minor or no activity on the border. During periods of increased PLA activities, such as in the case of Trig Heights, Pangong Tso, Rechin La and Demchok in the western sector, it is evident that there was a distinct lag before adequate response was effected in these areas,’ says the Border Management report. Moreover, as compared to the PLA, the infrastructure on the Indian side leaves much to be desired. For example, the 200km Sub-Sector-North in Northern Ladakh under the ITBP is presently air maintained. Although the government cleared construction of a class 9 road from Darbuk to Daulat Beg Oldi in year 2000 for Sub-Sector-North, the work has not begun. Therefore, single-pointcontrol and speedy development of infrastructure on the LAC with China are essential elements for border management. These will help foreclose options of the PLA to grab Indian territory and prevent embarrassment on loss of territory by our own mistakes.

Many benefits will accrue if the ITBP comes under the operational control of the Army. The latter, after the Kargil war in 1999 has deployed its Rapid Reaction Force in the immediate depth to the ITBP posts. A formalised mechanism will ensure a free flow of information between the ITBP company headquarters and local army units for better physical coordination between the two. Joint patrolling by the two forces will also be better conducted up to areas within India’s perception of the LAC in all sectors. Moreover, flag meetings and border personnel meetings with the PLA are on the rise. At present, these are done jointly by the Army and the ITBP at Chushul with no clear cut areas of responsibilities. “These will become more focussed once the ITBP comes under the operational control of the army,” says a member of the Border Management Task Force. And most importantly, modernisation of the ITBP equipment so that it is at par with the army Infantry units would be smoother if the two have formalised interaction. DG Agarwal,

however, does not agree. “The ITBP is in constant touch with the army regarding equipment. We have been allocated Rs 20 billion over a five-year period for both hardware and software, which includes weapons, surveillance means, better high altitude clothing, and other specialised equipment like GPS, fast patrol boats, digital cameras and so on,” he says, adding that, “the present co-ordination during peacetime and operational control in an event of war with the army is satisfactory.” The question is why would China go to war with India, when it is constantly nibbling at India’s territory to improve its tactical position on the ground?

This apart, the ITBP has other challenges to tackle as well. To begin with, says the DG, “We lack adequate infrastructure in areas of deployment. The government has recently allocated Rs 2 billion for it, and we hope to also have a dedicated air wing for the force,” he says. “Then there is a constant psychological, physical and mental attrition of men due to the inhospitable conditions and area of work. But to ensure proper rest and recuperation and adequate training, the government is considering some low altitude/ plain area deployment for the ITBP.” However, a former DG of ITBP feels that the force is overstretched. He says, “The ITBP talent is being wasted on tasks like VVIP security and ROPs which are exacting in nature. An average ITBP jawan gets to sleep once in two days.” If true, this is alarming. Probably the ITBP needs to discard its police orientation completely. For this reason, the Border Management report has suggested that the name of the ITBP be changed to ITBF (Indo-Tibetan Border Force) to conform to the role it performs on the border.

Hill Force

Alternately called the ‘Sentinels of the North East’ and ‘Friends of the Hill People’, the Assam Rifles is the oldest and a different paramilitary force. While it comes under the MHA, it is totally controlled by the army. Nearly 80 per cent of its officer cadre, from the DG to the battalion commanders, is on a three to five years deputation from the Army. The operational policies of the AR are decided by the Army. All logistics for the AR like transport and communications are also provided by the Army. The only thing non-army about this force is the rank structure which is akin to other paramilitary forces. “Like the DG, Rashtriya Rifles (RR), I have no operational control over the force,” says the DG, AR, Lt. Gen. H.S. Kanwar, who, before his present appointment, was the chief of staff, Western Command. The DG is responsible for providing the force with food, clothing, weapons and ammunition, ensuring discipline, training and recruitment, its civic action plans, its annual budgetary allocations, and its morale.

Unlike the RR which was raised in 1990 and has total recruitment from the army, the AR was raised in 1835 as Cachar Levy and was supposed to have a police heart and military training. It got its present avatar in 1917, when it was renamed as Assam Rifles with permanent headquarters in Shillong. Earlier almost all its recruits used to be from the North East, with Gurkhas forming a substantial proportion amongst them. However, in recent years, this has changed and AR has acquired an all-India character with only 15-20 per cent of the men coming from the North East. The force’s first Indian Inspector General from the army Col. Sidhiman Rai assumed command in September 1948. Just as its name changed over the years, so did its character. From a defensive force policing the borders in and around Assam, of late it has been involved in CI operations as well. In recent times, the AR has been employed extensively outside the North East; as part of the Indian Peacekeeping Force in Sri Lanka, in Punjab, and Jammu and Kashmir.

At present, the AR has two roles. “It does Counter Insurgency (CI) operations in Manipur, Mizoram, and Nagaland. Its border guarding role in these places is only on paper. The force’s other role is border guarding under the army on the Indo-Tibetan border in Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh,” says Lt Gen. Kanwar. For these twin roles, the AR battalions have two types of structures. For CI duties, the battalion has 15 officers, 61 Junior Commissioned Officers, and 1,425 other ranks making a total of 1,501 persons. Each company has three platoons and four sections instead of the normal three sections to a platoon. The border guarding battalions have 16 officers, 71 JCOs, and 1,539 men, making a total of 1,626. This is so because an additional com- pany is authorised for manning the supporting weapons like MMG and mortars.

With a strength of 40 battalions, the AR hopes to add another seven battalions by 2007. “The strength of the AR lies in the fact that this force is readily available to the Army in peace and war,” says Lt Gen. Kanwar. The DG, however, feels that the AR would be further strengthened if it is not divided between the MHA and the MoD. “The AR should either be under the MHA or the MoD, and the DG should have operational control rather than only administrative control over the force,” he says. Even as he does not say so, he prefers to be under the MoD. “The AR has army ethos, training and capabilities which are good for the force,” he quips.

The Border Management report, however, does not think so. It has made two recommendations: That the AR should be transformed into a full-fledged border guarding force under the MHA on the lines of the BSF and ITBP. And, under the ‘one border, one force’ principle, the AR should withdraw from the border with China and instead take the responsibility for the Indo- Myanmar border. For example, the BSF is deployed on 32km of Indo-Myanmar border in Mizoram close to Parva. The BSF should withdraw from this segment which will be manned by the AR. In view of the location of the tri-junction of India, Bangladesh and Myanmar at Parva, it is, however, necessary for the BSF and AR to work out formal measures of coordination between them to ensure that the tri-junction does not become vulnerable. It is understood that the government has accepted both recommendations and work has commenced. Considering that the AR will be confined to the North Eastern states, including the Myanmar border, it is suggested that at least, 50 per cent recruits in this force should be from within this region.

However, complete transition to the MHA will not be easy. Many new things will need to be looked into. To begin with, the force will need a new uniform. The officering of AR will be done on the same lines as the BSF and ITBP. The army officers presently serving in the AR would be given the option of either getting absorbed in the AR cadre, or continue on deputation for a specified period before going back to the army. The AR Act would need to be modified to reflect the new changes, and the AR would be empowered with various other laws pertaining to customs, narcotics, foreigners and criminal acts to prevent illegal migration, smuggling and other crimes. Moreover, like other border guarding forces, the AR will also be placed under the operational control of the army when any area is declared as ‘disturbed’ and Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act is made applicable. Importantly, the DG, AR would be selected and appointed by the MHA. Given that all these issues are complex, especially in regard to officering of the AR battalions, sector and IG headquarters, and the endless dependence of the AR headquarters on army logistics and command and control, it is certain that this would need close examination and hence it would be sometime before the AR comes completely under the MHA.

The Khaki Order

The Central Reserve Police Force’s (CRPF) first Director General, V.G. Kanetkar deserves to be praised for his concept of the force with Group Centres. “The idea was that men travel light and fast carrying minimal equipment. The nearest Group Centre to their employment is meant to provide them with operational logistics and administrative support,” says the DG, S.C Chaube. Much has, however, changed between 1968, when the Group Centres were introduced, and now. The roles and functions of the force have increased disproportionate to its infrastructure, equipment and training. So much so, that the CRPF calls itself a paramilitary force which it is not (the CRPF website). The CRPF is an armed police force of the Union of India, with the basic role of striking reserves to assist the states in police operations to maintain law and order and contain insurgency. With this in mind, it was decided that the concerned state government would provide the CRPF with basic dignified living amenities, while the Group Centres would cater for their professional requirements.

On both counts, the results have been unsatisfactory. “The CRPF is in aid of a state which is required to provide transport, electricity, water, and accommodation to them. Unfortunately, these basic things are not available and men have to live in inhuman conditions. Moreover, being on constant move, the men do not have a family life or even a permanent address, which causes domestic troubles as well. All this leads to psychological disorders which pushes them to sometimes shoot their colleagues or commit suicide,” says Additional DIG, A.S. Sidhu. Even the Group Centres are bursting at the seams. “A Group Centre cannot provide accommodation for more than four battalions, whereas now they have nearly five battalions with one additional company in each battalion. We have taken up the matter with the government,” says DG Chaube, adding that, “because of continuous deployments, the training of men is suffering. At least 25 to 30 battalions should be notified by the government as resting battalions. These can then be utilised for refresher training or for rotation of personnel.” What Chaube does not say is that many temporary training centres have been formed to cater for the fast expansion of the force. Insiders concede that the level of training at make-shift centres cannot be of a high quality.

At present, the CRPF has 140 battalions which by 2005 will become 205. Of these, 125 battalions have seven companies each, and the remaining battalions are also being brought at par. The expansion of the force, therefore, is happening both ways, more battalions and more men in each battalion. The present 30 Group Centres will increase by another eight. In terms of numbers, the force after expansion will have 230,000 men including 2,700 officers and 370 doctors. Also included are 10 Rapid Action Force battalions which specialise in anti-riot activities and are expected to be ready in a zero-time limit, and two Mahila battalions.

“The CRPF has no specified role,” says DIG Sidhu. The orginal role of the CRPF was well-defined and included crowd and riot control, counter- militancy operations, and rescue and relief in times of natural calamities. In recent times, many more jobs have been added. These range from security of VIPs and vital installations, duties at various melas and rallies where the force is required to move at a short notice, and elections duties (which have emerged as a major task) to name a few. The CRPF is deployed in a big way in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Orissa, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, Chattisgarh, West Bengal and so on.

The bulk of the force, however, is in Jammu and Kashmir where its charter of duties has undergone a major change. “The CRPF was doing defence operations in Jammu and Kashmir which included domination of an area, patrolling, including Road Opening Parties duties, and guarding of vulnerable areas, such as Raghunath temple, Vaishno Devi shrine, the state secretariat, and providing security to a select VIPs,” says Inspector General, Jammu range, C. Balasubramanium. The CRPF is now taking over counterterrorism duties from the BSF in the state in phases beginning with the Valley. A total of 39 battalions will be in the border state. These will be provided offensive and quick firing weapons. “We have received 17,037 AK rifles from Bulgaria. We have also asked the government for Anti-Grenade Launchers and mortars, and even the South African Cassiper vehicles meant for detecting Improvised Explosive Devices,” says DG Chaube. The other modernisation equipment includes, “81mm mortars, MMGs, the 5.56mm INSAS rifles to replace the existing 7.62mm, lighter bullet proof jackets, and night vision devices,” says DIG Sidhu. The government has accepted the force modernisation plan of Rs 5.4 billion over five years.

What most officers in the force concede but do not say openly is that the training for fighting terrorism in J&K will not be an easy task. “The CRPF will have to be prepared to initially take a lot of casualties,” remarks a paramilitary force DG. The other reason for this is that the CRPF does not have an intelligence branch (called General or G branch in the BSF), a must for anti-terrorism operations. “It will take up to 3 years for the CRPF to have a good G branch in J&K,” feels IG Balasubramanium. The other fear is that the CRPF would be left with no soft postings. “At present, one-third of the force rotates between hard and soft postings,” says DIG Sidhu.

According to CRPF cadre officers, a part of the blame for CRPF’s state of affairs is because of the IPS officers who occupy all the top slots. “Unlike the IPS officers’ all India Association, the CRPF cadre officers are not allowed to have a union. The IPS officers do not understand the force and simply flog it. If things continue like this, the force will collapse,” says a senior CRPF officer who is well versed with the state of the personnel training and morale. While this may be an exaggeration, the truth is that the CRPF has a multitude of tasks and requires good training and morale boosting measures, something that its new DG will need to ponder over.

Also Read:

Gunning for a Definite Role

BSF’s case for having its own artillery