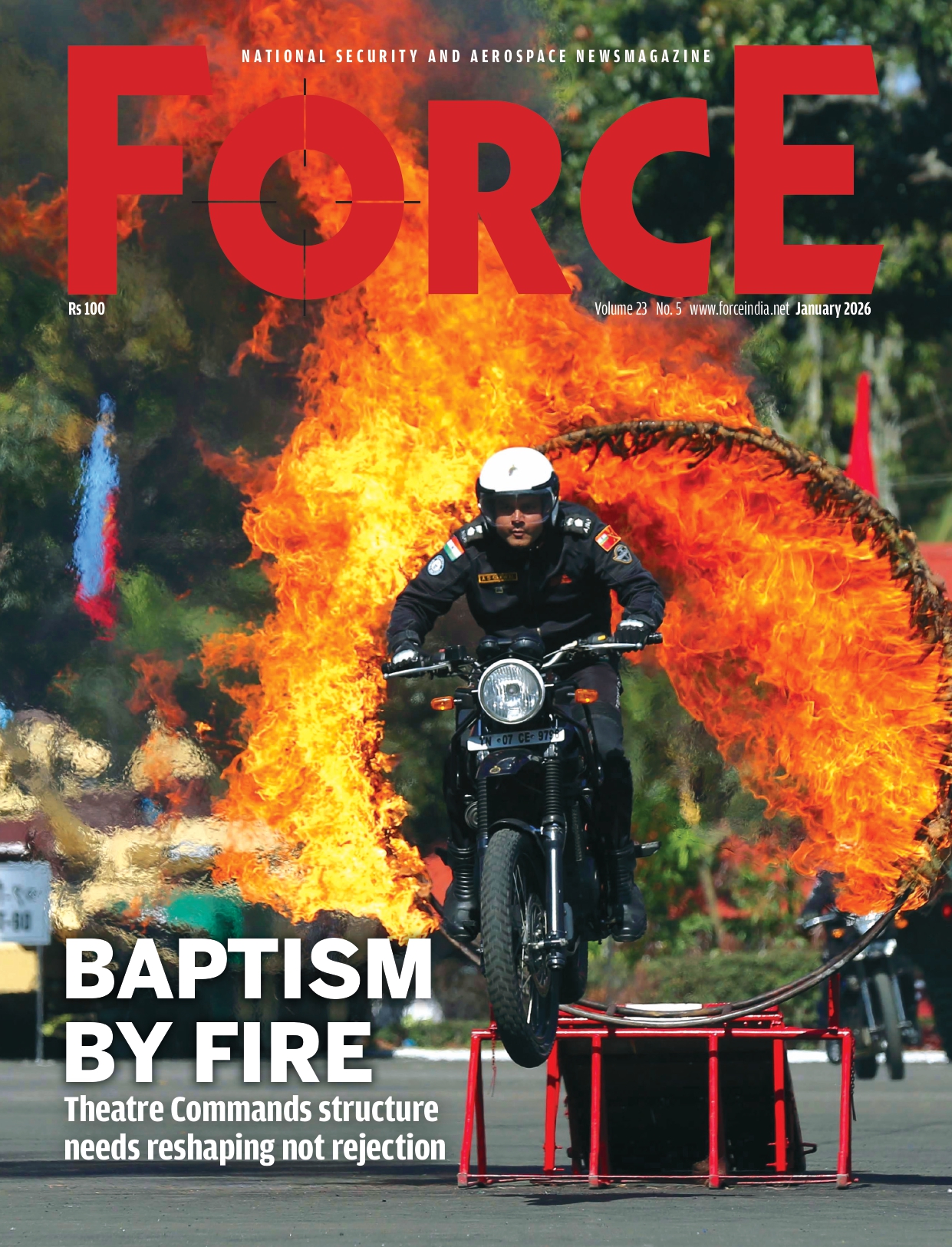

SHORT TAKES

MORE HEADLINES

.png)

Airbus Secures Historic Order for India’s first H175 and two ACH160s

Airbus Secures Historic Order for India’s first H175 and two ACH160s

Industry News

DRDO Flight-Tests Man Portable ATGM With Top Attack Capability Against a Moving Target

DRDO Flight-Tests Man Portable ATGM With Top Attack Capability Against a Moving Target Service News VIDEO

VIDEO

For BRICS Success, India Should Deepen Communication with Russia At All Levels

Shashi Tharoor is Wrong. Op Sindoor Shifted Regional Balance of Power in Pakistan's Favour

Why President For War, Trump, Wants Greenland

COLUMNS

Please bear with us for a few days. We are making ourselves better

Subscribe To Force

Fuel Fearless Journalism with Your Yearly Subscription

SUBSCRIBE NOW

We don’t tell you how to do your job…

But we put the environment in which you do your job in perspective, so that when you step out you do so with the complete picture.

.jpg)