Guest Column | Lessons from the Past

Cmde Lalit Kapur (retd)

Cmde Lalit Kapur (retd)

During his keynote address at Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation on 14 May 2017, Chinese President Xi Jinping painted a rosy picture of what he described as ‘the project of the century’. The ancient silk routes, as per his speech, had embodied ‘the spirit of peace and cooperation, openness and inclusiveness, mutual learning and mutual benefit’, becoming a great heritage of human civilisation.

The pioneers who trod their paths, including Zhang Qian, Zu Huan, Marco Polo and Zheng He ‘won their place in history not as conquerors with warships, guns or swords’. Rather, they were ‘remembered as friendly emissaries leading camel caravans and sailing treasure-loaded ships’. He went on to talk of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) vision aiming to create enhanced policy, infrastructure, trade, finance, and people-to-people connectivity; of building the Belt and Road into a road for peace, fostering the vision of common, comprehensive, cooperative and sustainable security, with respect to the sovereignty, dignity and territorial integrity, development paths, social systems, core interests and major concerns of each nation involved.

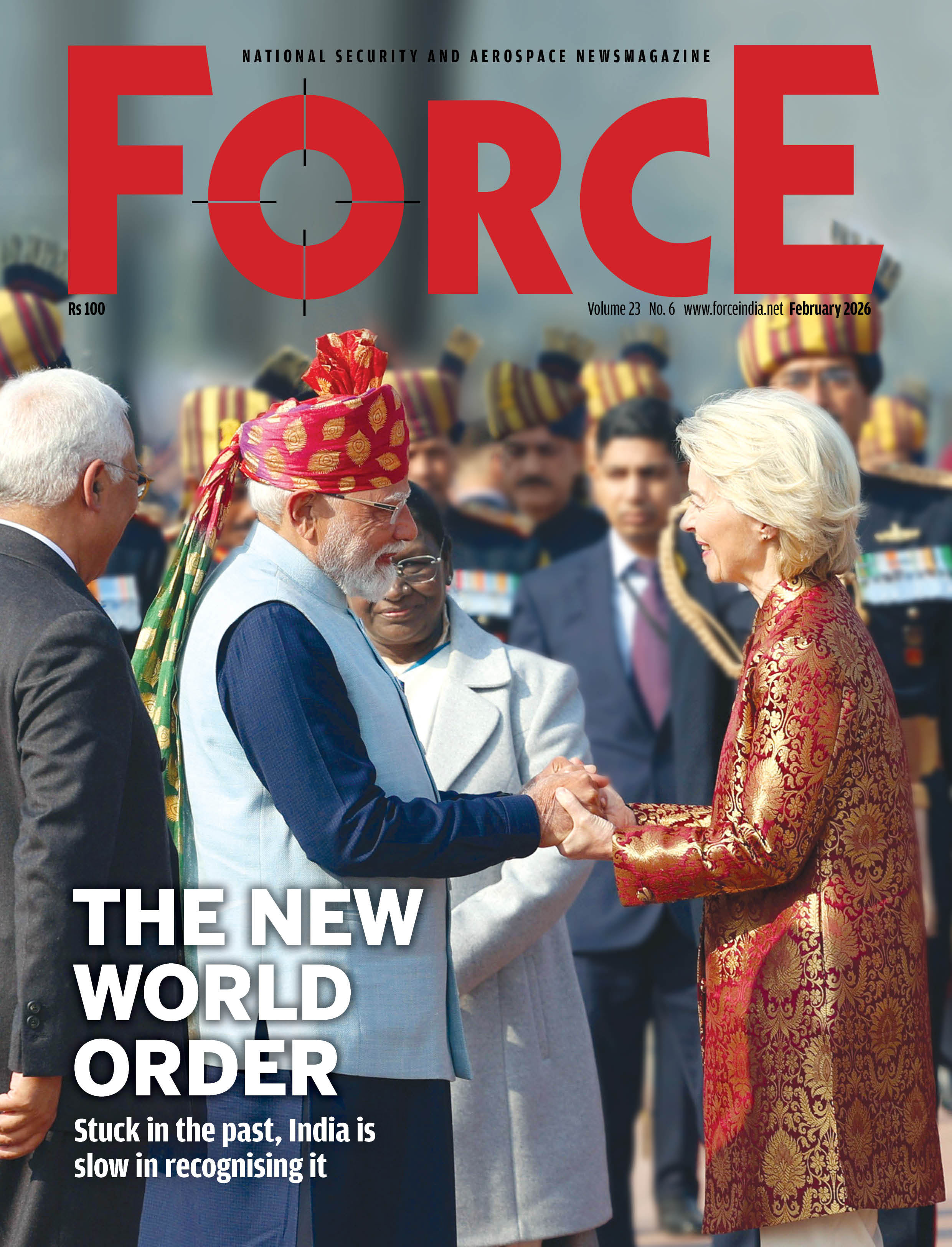

Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping with participants of the Belt and Road international forum

At first sight, the BRI vision certainly appears very attractive. The transcontinental part, the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB), comprises six rail, road, air and pipeline corridors connecting all of Eurasia. Two East-West corridors have been projected: the China Mongolia Russia Economic Corridor; and the New Eurasian Continental Bridge, going through Kazakhstan, Southern Russia, Ukraine, Poland and Germany. Four ‘feeder’ corridors will link Asia to the New Eurasian Continental Bridge: the China Central Asia West Asia Economic Corridor; the China Pakistan Economic Corridor; the China Indo China Economic Corridor; and connected to it, the Bangladesh China India Myanmar Economic Corridor. The Maritime Silk Road (MSR) is the oceanic face of this gigantic project, envisaging a network of ports and associated coastal infrastructure emanating from China’s Pacific Coast and stretching through Indo-China and Malacca across South East Asia, South Asia, the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, East Africa and the Mediterranean before going on to Rotterdam and Venice. There can be little doubt that the connectivity to be created will increase trade, particularly China’s trade, with Europe, Asia and Africa.

But, as the history of Asia proves, control over such connectivity can have long lasting geopolitical and military consequences. The Chinese ‘friendly emissaries’ named by Xi Jinping led to an expansion of the Chinese Empire, from its founding by the Xia Dynasty in a relatively small area of what now constitutes the Shando-Henan provinces of China, to its peak of over 13 million sqkm under the Qing Dynasty. Zhang Qian was the first envoy from the second century BC Han court to what is now Central Asia. His travels led to the Chinese colonisation and conquest of what is now known as Xinjiang, embodying neither peace nor cooperation, neither openness nor inclusiveness. Zheng He was the eunuch Admiral from the court of the Ming Dynasty’s Yongle Emperor (who deposed his nephew to seize the throne).

more

By some accounts, Zheng He’s voyages were primarily to search for the absconding nephew, making it the largest manhunt ever! The voyages were also intended to establish Chinese presence and impose imperial control over Indian Ocean trade while exacting tribute from kingdoms en route: Zheng He’s fleet during his first voyage to Champa, Java, Malacca, Ceylon, Quilon and Calicut c

Subscribe To Force

Fuel Fearless Journalism with Your Yearly Subscription

SUBSCRIBE NOW

We don’t tell you how to do your job…

But we put the environment in which you do your job in perspective, so that when you step out you do so with the complete picture.

VIDEO

VIDEO