Corporatised Conflict Management

In the deadline of the Maoist elimination lies the seeds of future resistance

Sudeep

Chakravarti

Sudeep

Chakravarti

And

so, to 31 March 2026. The often-repeated official deadline to rid India of the Maoist

rebellion that in one form or another, as factions or as conglomerates, has

existed continuously since 1967.

This

claim is predicated on a string of spectacular gains this year, particularly

the death in May of Nambala Keshava Rao, known by his nom de guerre, Basavaraju, in the Abujhmad forests of Chhattisgarh

during an attack by security forces. Rao took over as general secretary of the

Communist Party of India (Maoist), or CPI (Maoist), India’s largest leftwing

rebel conglomerate, in 2018.

The

Maoist enterprise has bled leaders and cadres by the hundreds this year. Arrests

and surrenders across the primary Maoist operational areas of Chhattisgarh,

Telangana, Maharashtra, Odisha, and Jharkhand are collectively at over two

thousand, among the highest in any year since the peak of the Maoist movement

in 2004-2009. At that time nearly a third of India’s 600-odd districts were

described as affected by leftwing extremism, or LWE in officialese.

Home

ministry figures in December 2024 clocked 38 districts across nine states as ‘LWE

affected.’ In October 2025, the ministry claimed it was down to 18 districts. Meanwhile,

an overture for a truce and negotiations in September was rebuffed by India’s

home minister, who set that deadline akin to a business plan for the end of

this financial year.

As

momentum gathers to write obituaries of the Maoists it is incumbent on our

triumphalist impulses to gauge the rationale and trajectory of the movement.

This is instructive. After all, among India’s many wars with itself over

variously denying citizens governance, constitutional rights, dignity of

identity and aspiration, a sense of equity in the nation, and effective

delivery of the criminal justice system, the conflict with Maoist rebels—or

Naxalites as the government and media have frequently mislabelled them—remained

among the most vexing.

After

the state reclaims areas from the Maoists, unless it delivers inclusive,

reliable governance, rebellion—or at least resistance—will persist. Repeated

protests by farmers in Punjab and Haryana, protests in Kashmir, and most

recently protests in Ladakh, are typical. Anger stems from broken promises and

savage vilification by government officials and state-led media, among other

things.

And

that is really the point. While one can bulldoze a way to absence of conflict,

peace is earned through trust and credibility of governance. Until that

happens, the vacuum will be filled—by Maoists, or someone else.

For

all their brutality, extortionist economy, kangaroo courts, and accusations of

being out of touch with the aspirations of a modernising country, the

uncomplicated truth is that the Maoists—like several violent or non-violent

movements across India—have for decades mirrored India’s own failures. Maoists

did not ask to break away from India, but to change the way India functions.

My

learned colleague in conflict mapping and conflict resolution, Ajay Sahni, has for

long had an apt term for it: ‘Privileging violence.’ My go-to phrase is ‘mall-stupor.’

We suggested—suggest—the same thing. In an increasingly tone-deaf country, unless

people ratchet up their protest to demand what they should in any case be

receiving through positive governance, they receive little or nothing.

Maoists

twigged on to this decades ago. It began with escalating leftwing protests and

violence in the 1940s and 1950s to great violence in the 1960s. With its roots

in the Tebhaga movement, this upwelling for fair income for farmers in the

Naxalbari region on northern Bengal—the root of ‘Naxalism’, ‘Naxal’ and

‘Naxali’—spread elsewhere, with demands to reduce caste dominance in undivided

Bihar and Andhra Pradesh, reduce inequities in Punjab, and so on. In the 1980s

and 1990s it morphed to include justice for tribal folk and ‘forest dwellers.’ After

CPI (Maoist) was formed in 2004, LWE increasingly embraced positions against

mining- and project-led displacement.

Live

and learn. If exploitation continues, and land grabs, crony capitalism, or

failed rehabilitation of both displaced folks and former rebels, we are only

sowing the seeds of dissent.

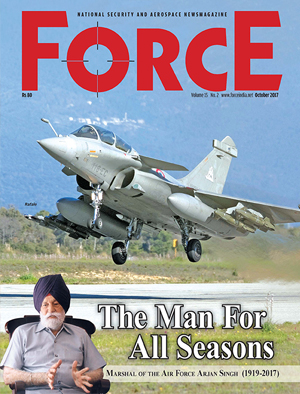

HAUL OF THE DAY CRPF with arms cache after counter Maoist operation near Jharkhand

Or

it could be like Kashmir where, we were told, terrorism and troubles would end

with demonetisation in November 2016; and again, in 2019, after the revocation

of Articles 370 and 35A of the Constitution. Because beyond triumphalism there

must be active policy to replace a hammer-fist with governance, rights, and sense

of equity; and to move from the economy of conflict to the economy of peace.

These

must be the true objectives beyond tricky deadlines of winning wars against our

own people—which is deeply perverse in any case—or we sow the seeds of the next

conflict. A continuous conflict.

Also

tricky: Immaculate misconceptions of claiming sole credit for victories.

The

latest iteration of grinding down the Maoist rebellion is a two decade-old

project. In 2006 the United Progressive Alliance government created the Naxal Management

Division in the ministry of home affairs—later the LWE Division. It was an

operational hub for coordinating anti-Maoist efforts across states, which had

until then acted independently. For example, Andhra Pradesh’s elite Greyhounds

largely operated in isolation, as did forces in Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, Jharkhand,

Odisha, and so on. Cross-border rebel movement was difficult to counter due to

jurisdictional limits.

From

2006 to 2008, the ministry began encouraging more joint operations. In 2008,

the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) launched its specialised units of CoBRA

or Commando Battalion for Resolute Action, first deployed in Chhattisgarh. More

states developed their own specialised forces and extensions. In Chhattisgarh,

the controversial Salwa Judum militia emerged—recruiting tribal youth, often by

coercion, to fight against fellow tribals seen as Maoist sympathisers. It divided

communities. Maoists had in any case begun recruiting from these same tribal

populations—or victims of displacement and caste and general oppression.

States

began to take a broader approach—recruiting and training district police, often

from the same marginalised communities, weaning them away from Maoist

influence. The Centre and states launched military-style operations,

intelligence-sharing and actionable intelligence that began to be acted upon,

more infrastructure—and, occasionally, better governance.

As

initiatives like the Right to Information Act and Integrated Development Plans

in conflict areas took shape, governance improved in some of these neglected

areas—bringing primary healthcare, education, the criminal justice system, and

legal aid.

Action

plans for each theatre had its genesis in UPA, when as minister for rural

development Jairam Ramesh oversaw two ‘models,’ the Saranda and Sarju action

plans in Jharkhand to follow a hub-and-spoke approach to provide basic

utilities, healthcare, education and communication, following ultra-local

operational successes of reclaiming territory from Maoists. This has remained a

go-to plan.

As services began to reach some communities after Maoist zones were ‘sanitised’, the appeal of rebellion diminished. Governance, when finally delivered, did what ideology no longer could.

From

2010 or so, the Indian Air Force and Army Aviation began to provide logistical

support. Aerial surveillance and satellite imagery became more common. While

the current government has expanded these tools, the operational blueprint evolved

with the creation of the Naxal Division. Increasingly, the Maoists faced the

full might of the Indian state—superior resources, firepower, and institutional

reach.

Alongside

military pressure, surrender and rehabilitation schemes across affected states

have also offered Maoists, including leaders, a way out: short jail terms or

cooling-off periods, followed by reskilling and reintegration into civic and

political life. It has been a sustained, multi-layered strategy—military,

political, and social—that has brought us to this moment.

The

National Democratic Alliance government wholly adopted the approach of its

predecessors and then began to appropriate the vocabulary. In May 2017, Rajnath

Singh, who was home minister at the time, announced an acronym: SAMADHAN, or

solution. It came in the wake of a Maoist attack in Sukma in southern Chhattisgarh,

where 25 CRPF troopers were killed by rebels that April.

SAMADHAN,

as we learned, was a contraction of ‘Smart leadership, Aggressive strategy,

Motivation and training, Actionable intelligence, Dashboard-based KPIs’—key

performance indicators—‘and KRAs’—key result areas—‘Harnessing technology,

Action plan for each theatre and No access to financing.’

This

corporate approach had some fuzzy logic, as I wrote at the time. While training,

technology, actionable intelligence and squeezing financial channels were clear

enough, what exactly would KPIs and KRAs include? These many Maoist heads per

trooper? Fixed collateral damage per company of troopers—one rape and two

torture episodes per 10 arrests? Each patrol must walk not less than 15km a day

in hostile areas, of which three kilometres must be at a trot? Would each

district at war need to provide 50 surrendered rebels every quarter?

It

was as if a complicated internal war of enormous social, economic and political

significance was distilled to a performance appraisal drawn up by an automaton

in human resources.

And

here we are: A projected end to the Maoist rebellion by the end of the 2025-26

financial year—the operative calendar of government machinery that revolves

around the calendar of planning budgets.

But

here’s the thing. Especially over the past decade we have observed the weaponising

of law and the weaponising of labels—the disinformation-led trope of ‘Urban

Naxal’ is only one such—to silence dissent and discredit even basic demands for

better governance. Citizens asking for roads or equity or justice are painted

as enemies of the state. Those targeted are increasingly citizens offering

feedback, sometimes dissent, most often just a suggestion.

This

is the twilight zone where rebellion lives.

(The writer works in the policy-and-practice space in South Asia and the

Indian Ocean Region. Alongside various other geographies of conflict and

conflict resolution, he is also a longtime observer of Maoist rebellions in

South Asia)

Subscribe To Force

Fuel Fearless Journalism with Your Yearly Subscription

SUBSCRIBE NOW

We don’t tell you how to do your job…

But we put the environment in which you do your job in perspective, so that when you step out you do so with the complete picture.