Building Bonds

The Safran-DRDO fighter engine deal opens a new

chapter in Indo-French strategic partnership

Junaid Suhais

Beneath the glare of geo-strategic spotlights, some alliances are like grandmasters quietly moving their pieces deep into mid-game, anticipating shifts before the world catches on. India and France, once content advancing pawns across distant squares, now move queens and castles in synchronised arcs. A Rafale Marine jet thunders above the blue while a jet engine hums to life in a Hyderabad lab, each a calculated move in a match where mastery is measured not in domination, but in the power to co-design the board itself.

OCEAN KING Rafale Marine

With an investment of Euro 36 million

and located on 10 acres of land in

the Hyderabad SEZ, Indian and French

engineers are co-developing the beating

heart of a future stealth

fighter, a jet engine, the pinnacle

of aerospace technology. These two silhouettes, one cast by the prowling might

of operational power, the other by the quiet pulse of industrial creation, are

not parallel lines, but converging vectors. Together, they support a relationship that has shed the linear logic of mere buyer and seller, forming

instead the dual scaffolding of a partnership matured into a genuine co-architecture

of strategic capability.

The 2025 Intergovernmental Agreement (IGA) for the acquisition of 26

Rafale Marine jets, alongside the

pioneering Safran-Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO)

collaboration to co-develop a next-generation fighter engine, transcends mere

transactional contracts. They script the unfolding chapter in the enduring saga of India-France strategic cooperation, a narrative where shared conviction in strategic autonomy drives a

decisive shift from conventional procurement to profound technology transfer, evolving from transactional

allies to co-architects of sovereign power in a turbulent global theatre.

The Historical Arc

Over successive decades, this relationship has evolved, from early arms

acquisitions to comprehensive strategic

cooperation, adapting continuously

to serve the dynamic security and industrial imperatives of both nations.

From Ouragan

to Mirage: The first major milestone was the

1953 deal for 71 Dassault Ouragan

fighter jets, known in the Indian Air Force (IAF)

as the Toofani. These jets served India extensively, from ground

attacks during the liberation of Diu in 1961 to

reconnaissance in the 1962 Sino-Indian War and

became emblematic of India’s early steps toward self-reliance in

military aviation.

This was a pragmatic decision by India to equip its air force with a capable

platform while simultaneously signaling its intent to pursue an independent

foreign policy. This initial engagement set a crucial precedent: France proved

to be a reliable partner, unencumbered by the Cold War alignments that often complicated dealings with other major powers.

This trust was reinforced in the

Eighties with the acquisition of Mirage 2000. At a time when India faced a complex regional

security environment, the Mirage provided the IAF with a cutting-edge,

multi-role fighter that offered a significant technological advantage. The

subsequent upgrade of the Mirage fleet and

France's unwavering support,

especially its refusal to impose

sanctions after India’s 1998 nuclear tests, cemented its reputation in New Delhi

as an ‘all-weather’ friend. This political reliability became a cornerstone of the relationship,

formally institutionalised with the signing of a Strategic Partnership

in 1998.

Deepening the Waters: The partnership expanded from the skies to the seas with the 2005 agreement for six Scorpène-class (Kalvari-class) submarines, to be built in India by Mazagon Dock Limited (MDL) with technology transfer from France’s Naval Group. This project was a quantum leap in industrial collaboration. It was not merely an off-the-shelf purchase but a complex co-production initiative aimed at revitalising India’s submarine-building capabilities and furthering its goal of Aatmanirbhar Bharat (self-reliant India) in defence. The Kalvari-class submarines, equipped with advanced features like air-independent propulsion (AIP) systems being developed indigenously, now form a critical component of India’s underwater deterrence.

The Rafale Era Begins

The acquisition of 36 Rafale fighters for the IAF in 2016 marked the most significant defence deal

between the two countries to date. Valued at approximately Euro 7.87 billion, the agreement provided the IAF

with a 4.5-generation ‘omnirole’ aircraft, capable of performing a wide spectrum of missions from air superiority to deep-penetration strikes and delivering nuclear payloads. The deal

went beyond the aircraft themselves, including a comprehensive package of

India-specific enhancements, advanced weaponry like Meteor and SCALP missiles,

and a commitment to performance-based logistics. It was a clear signal of India’s

intent to maintain a qualitative edge

in a contested neighbourhood.

Rafale Marine MoU:

Building on the success of the IAF contract, the signing of the Intergovernmental Agreement on 28 April 2025, for 26 Rafale Marine jets for the Indian Navy represents a pivotal moment. It highlights a strategic convergence, aiming to develop a powerful synchronisation between India’s air and naval forces.

The agreement, valued at approximately Euro 7 billion, is a

comprehensive package designed to

rapidly enhance the Indian Navy’s carrier-borne aviation capabilities. The core components, as outlined in the official

press release, include:

- Aircraft Fleet: A total of 26 Dassault Rafale jets, comprising 22 single-seat Rafale M (Marine) variants for carrier operations and 4 twin-seat Rafale D variants for training purposes.

- Delivery Schedule: Deliveries are set to begin in 2028 and are expected to be completed by 2030, a timeline that addresses the navy’s urgent need to replace its ageing and unreliable MiG-29K fleet.

- Support Ecosystem: The deal includes a five-year Performance-Based Logistics (PBL) support package. PBL is an outcome-focused strategy where the provider is incentivised to ensure asset availability and mission readiness, rather than just selling spare parts. This ensures higher operational uptime for the fleet. The package also covers training, simulators, and associated equipment.

- Industrial Participation: Crucially, the IGA includes provisions for setting up production facilities for the Rafale fuselage in India, as well as Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul (MRO) facilities for the aircraft's engine, sensors, and weapons. This aligns directly with India’s ‘Make in India’ ambitions. The existing Dassault-Tata joint venture in Hyderabad for fuselage manufacturing is a prime example of this deepening industrial collaboration.

The Strategic

Dimension

The procurement of the Rafale-M is a move laden with strategic

significance. It is an interim solution

to bridge the capability gap until India’s indigenous Twin Engine Deck-Based

Fighter (TEDBF) becomes operational, expected around 2031-2032. However, its

impact goes far beyond being a

stop-gap measure.

Commenting on the signing, Ambassador

of France to India Thierry

Mathou said, “Today’s agreement marks a significant new milestone in the

strategic partnership between France

and India. Reflecting the deep mutual trust and confidence that underpin our defence cooperation, it also

highlights the ability

of the French industry to align

with India’s evolving needs.”

Capability Symbiosis: The most immediate benefit is the high degree of commonality between

the Rafale-M and the IAF’s existing Rafale fleet. This ‘capability symbiosis’

will streamline logistics, maintenance, and training, reducing life-cycle costs

and enhancing operational interoperability. Pilots and ground crews can be

cross-trained, and spares can be pooled, creating a more efficient and

resilient warfighting ecosystem.

Maritime Power

Projection: The Rafale-M will operate from India’s indigenous aircraft

carrier, INS Vikrant, transforming it

into a potent instrument of power

projection. An aircraft carrier

is a floating embassy and a sovereign territory, allowing a nation to project air power

far from its shores. Equipped with the Rafale-M,

INS Vikrant can effectively police

the vast expanses of the Indian Ocean Region (IOR), secure

vital sea lanes of communication, and provide a credible deterrent against China’s increasing naval activities.

Integration Challenges: The path to integration is not without hurdles. The Rafale-M, with its fixed wings, is dimensionally larger than the aircraft lifts on INS Vikrant, which were designed for the smaller MiG-29K. This will require either minor modifications to the carrier’s elevators or innovative operational workarounds, such as removing wing pylons before moving the aircraft. While technically feasible, these procedures could impact the operational tempo on the carrier deck. This challenge highlights the trade-offs involved in adapting a foreign platform, reinforcing the long-term importance of the indigenously designed TEDBF, which will be tailored for Indian carriers.

The Safran Engine Agreement

If the Rafale deal represents the pinnacle of platform acquisition, the Safran-DRDO agreement to co-develop a next-generation fighter engine is a bold leap into the very heart of aerospace sovereignty. For decades, jet engine technology has been the ‘last frontier’ for India’s defence industrial base, a closely guarded domain dominated by a handful of global powers. Cracking this code is not just a matter of industrial ambition; it is a fundamental prerequisite for true strategic autonomy.

BELOW AND BOTTOM Signing of HAL and Safran Aircraft Engines agreement at Aero India 2025; and Safran M88 aero engine

The most revolutionary aspect of this deal is the commitment to 100 per cent transfer of technology (ToT),

including full access to design and manufacturing expertise, shared Intellectual Property

Rights (IPR), and know-how for critical components

like single-crystal turbine blades. This is a radical departure from past

collaborations, such as the deal with America’s

GE for F414 engines, which involved only partial technology transfer (around 70

per cent) and came with stringent

end-use restrictions under the US ITAR regime.

Why Engines Matter: India’s quest for an

indigenous fighter engine has been long and arduous. The GTRE GTX- 35VS Kaveri

engine project, initiated

in the Eighties to power the Tejas Light Combat

Aircraft (LCA), struggled for decades. It was plagued by

technological hurdles, a lack of

testing infrastructure, and crippling

international sanctions following the 1998 nuclear tests, which cut off access

to critical technologies. Ultimately, the Kaveri failed to produce the required

thrust, and India had to import GE

F404 engines for the Tejas. This

setback was a stark reminder that

without mastering propulsion technology, any ambition of building a truly

indigenous fighter aircraft would remain incomplete.

Economic and Industrial Impact

Cost and Scale: The project is estimated to cost

around USD7 billion and will

involve building nine prototypes over 12 years.

The Strategic Ecosystem

The Deal: Announced in August 2025, the collaboration between France’s Safran and India’s DRDO is a game-changer.

The project aims to design, develop, and produce a 110-120 kN thrust-class engine in India. This engine is slated to power India’s

futuristic fifth-generation stealth fighter, the Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft (AMCA).

These two landmark deals do not exist in a vacuum. They are the operational and

industrial manifestations of a deep

and expanding strategic alignment, particularly

focused on ensuring a free, open, and stable Indo-Pacific. Both India and France

view themselves as resident

powers in the region: India through

its vast coastline, and France through its overseas territories such as Réunion

Island. This shared geography informs a shared strategic outlook.

From Bilateral Exercises

to Trilateral Cooperation: The Indo-French Defence

partnership is characterised by a high level of operational interoperability,

honed through years of complex joint exercises. The flagship naval exercise, ‘Varuna’, initiated in 2001, has evolved into a sophisticated drill involving aircraft

carriers, submarines, and maritime

patrol aircraft from both navies.

These exercises are crucial for practicing everything from

anti-submarine warfare to cross-deck operations, ensuring that both navies can

work together seamlessly in a crisis.

This bilateral cooperation is now expanding into trilateral and multilateral formats. The India-France-UAE Trilateral is a prime

example, leveraging the strategic

locations and capabilities of all three

nations to enhance

maritime security in the Arabian

Sea and the wider Indian

Ocean.

The French Difference

What makes the partnership with France unique for India?

The answer lies in a combination of political

reliability, a shared philosophy of strategic autonomy, and a willingness to share high-end technology

without the restrictive conditions often imposed by other partners.

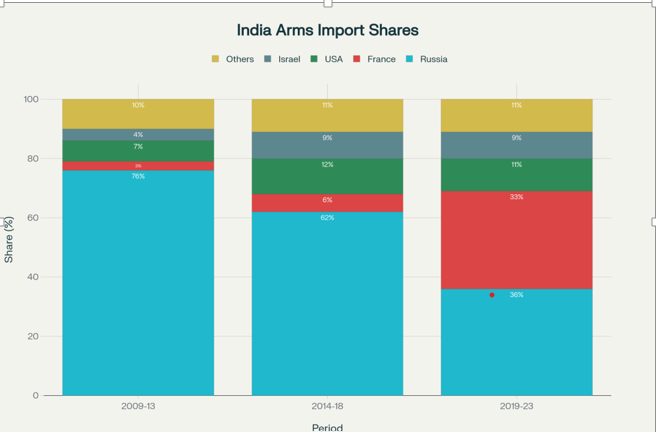

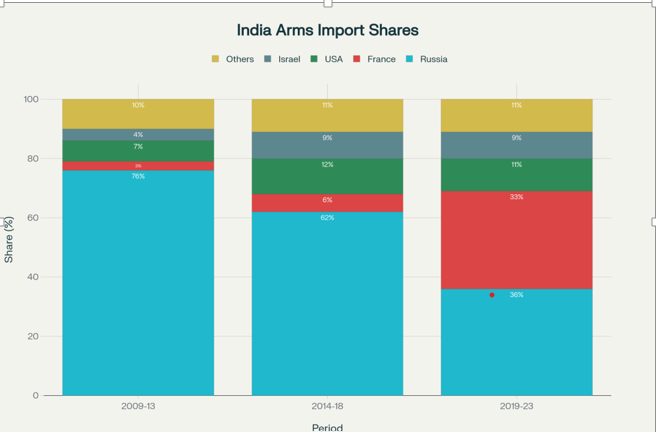

Versus Russia: For decades, Russia was India’s primary defence supplier. However, its

share in India’s arms imports has been steadily declining,

falling from 76 per cent in 2009-13 to just 36 per cent in 2019-23, according

to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). Concerns over supply chain reliability, post-Ukraine war sanctions, and a desire to diversify have pushed India to

look elsewhere.

Data Source: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), March 2024 Report

The Diplomatic Calculus

At its core, the India-France defence partnership is a masterclass in modern statecraft. It is a

relationship where national

interests align almost perfectly, creating a

powerful feedback loop of trust, technology, and strategic

convergence. For France,

it is a vehicle to assert its

status as a major Indo-Pacific power

and a global security provider, independent of the US-China rivalry. For

India, it is the most effective

pathway to achieving Aatmanirbhar

Bharat in Defence, de-risking its supply chains, and building

the military muscle required to underwrite its regional leadership.

The regular high-level dialogues, such as the annual Strategic Dialogue

and meetings of the Joint Working Group on Counterterrorism, provide the

diplomatic framework that nurtures this cooperation. The personal chemistry

between the leaders of both nations has also played a significant role,

transforming a formal partnership

into one of ‘strategic intimacy.’

Reflecting on the partnership’s evolution, one French diplomat observed, “Defence and security

really is the core of our partnership…

‘Make in India’ is a priority

for India, and all our big stakeholders in the defence industry want to play

the game. That means coming to India, building

in India, and transfer of technology. That’s the key.”

Data Source: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), March 2024 Report

Final Thoughts

The trajectory from the

Toofani

roar in 1953 to the co-development of a stealth fighter engine in 2025 delineates a saga of relentless

ascent and profound synergy. The Rafale jet, a

marvel of engineering, is the visible symbol of this alliance. But the

true measure of its depth lies in the unseen, in the engine, a complex machine built on a foundation of shared blueprints and

mutual trust. An engine is not just sold; its secrets are shared. It is a commitment to a shared future, a bet on a partner’s success.

Looking to 2035, the Safran-DRDO engine deal ushers

in a new epoch, with $7 billion invested, nine prototypes planned, and

complete technology transfer putting India at the edge of global propulsion

innovation. The era of AI-driven

warfare, unmanned ‘loyal wingman’ systems, and multi-domain

deterrence will demand even deeper integration. The foundation being laid today, through joint production, shared

IPR, and seamless interoperability, is precisely what will enable India and

France to manoeuvre this

ever-evolving future together.

With these developments, this partnership reaches beyond transactional procurement toward co-architectship, shaping the doctrines, industries, and the broader geostrategic theatre. The rhythm of turbine blades and the orchestration of carrier operations create a new strategic language, combining vision and shared sovereignty. In that hum of engines in Hyderabad and the glint of steel above the sea, one can hear the sound of a new strategic language, written not in treaties, but in trust, ready to shape the contours of the 21st century.

Subscribe To Force

Fuel Fearless Journalism with Your Yearly Subscription

SUBSCRIBE NOW

We don’t tell you how to do your job…

But we put the environment in which you do your job in perspective, so that when you step out you do so with the complete picture.