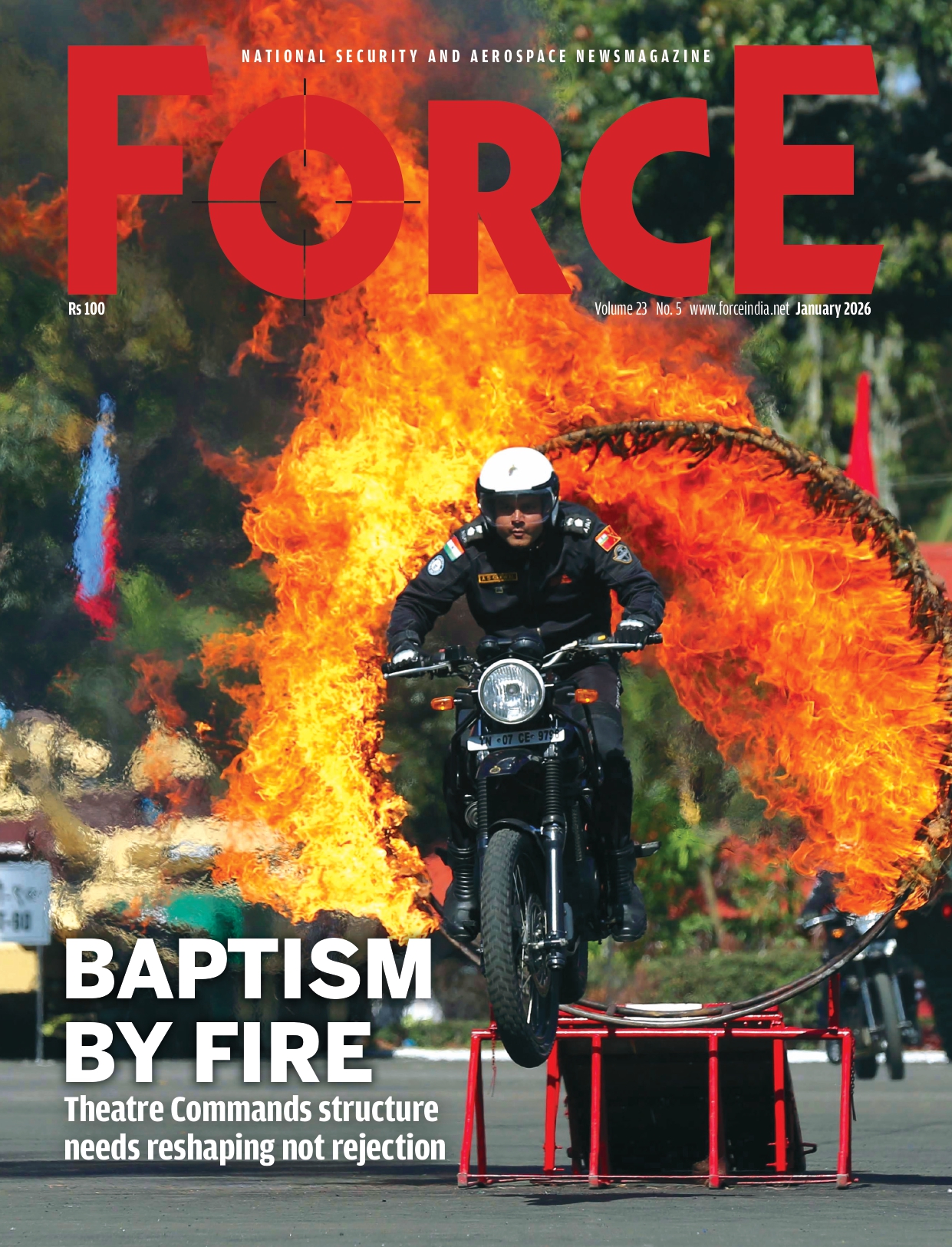

Baptism by Fire

Theatre Commands structure needs reshaping not rejection

Lt Gen. HJS Sachdev (retd)

Lt Gen. HJS Sachdev (retd)

The concept of theatre commands represents one of the most consequential structural reforms under consideration in India’s higher defence organisation. As modern warfare becomes increasingly multi-domain, time-compressed, and technology-intensive, the traditional service-centric command architecture is being reassessed worldwide. Integrated theatre commands bring land, air, maritime, cyber, and space capabilities under a unified commander.

However, the creation of theatre commands is not merely an organisational exercise. It carries profound implications for operational doctrine, force structuring, logistics, inter-service relationships, and resource allocation. Models adopted by major powers such as the United States and China, while instructive, are shaped by their own geopolitical ambitions, geographic scale, and economic capacity. India’s strategic circumstances demand a solution rooted in indigenous realities rather than imported templates. Consequently, in this article, I examine the rationale underpinning such commands in India and critically evaluate existing proposals in the backdrop of India’s unique strategic environment.

The Evolution

Conceptual Recognition: The first conceptual impetus can be traced to the Kargil Review Committee (KRC), 1999-2000, constituted in the aftermath of the Kargil conflict. While the KRC did not explicitly recommend the creation of theatre commands, it unequivocally highlighted serious deficiencies in joint planning, intelligence coordination, and command integration among the Services and laid down the intellectual foundation for integrated command structures by underscoring the need for jointness at the operational level.

Institutional Foundations: Building on the KRC’s findings, the Group of Ministers (GoM) on National Security Reform (2001) sought to translate conceptual recommendations into institutional reforms. The GoM recommended the establishment of the Integrated Defence Staff (IDS) and the appointment of a Chief of Defence Staff (CDS). Although theatre commands were not explicitly mandated, the GoM report recognised that integrated operational planning was indispensable for future conflicts.

A more direct articulation of theatre-level integration appeared in the Naresh Chandra Task Force Report (2012). The report acknowledged that India would eventually need integrated theatre commands to prosecute modern wars effectively. The Task Force treated theatre commands as a logical end state, contingent upon the evolution of joint doctrine, trust, and institutional maturity. The Shekatkar Committee (2016) added resource-optimisation and efficiency rationale. Its recommendations emphasised reducing duplication, improving combat effectiveness, and reallocating manpower and finances toward operational capability. Although primarily focused on force optimisation, the committee implicitly supported theatre commands to achieve unity of effort and cost efficiency.

lEFT & ABOVE The air and land segment of tri-service exercise

Bharat Shakti was held in Pokharan in 2024;

Prime Minister Narendra

Modi with defence minister Rajnath Singh at the exercise

Operational Advocacy and Policy Intent: For the first time, Integrated Theatre Commands were openly articulated as a reform objective rather than an academic construct, by the CDS in December 2019, General Bipin Rawat. He consistently argued that future conflicts would be multi-domain, time-compressed, and contested across multiple fronts, requiring unity of command and integrated employment of land, air, maritime, cyber, and space capabilities. Under his stewardship, theatre commands became central to India’s defence reform discourse.

The Rationale

Higher Defence Organisation: Theatre Commands bring in a clear separation of responsibility between force generation and force employment, with the present service HQs focused on the former and the Theatre Commands focused on the latter.

Unity of Command: Theatre commands place all relevant service components—land, air, maritime—under a single commander for a defined geographical area, reducing ambiguity and improving synchronisation in combat.

Multi-Domain Integration: The expanding role of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR), missile forces, cyber warfare, and space-based assets necessitate coordinated planning and execution across services.

Jointness and Integration: While the jointness can be achieved without unity of command but integration can only be achieved by joint planning for weapon systems, communications, training and procedures.

Resource Efficiency: Joint logistics, unified planning and acquisition in weapon systems, communications and common training frameworks reduce duplication and enable more coherent long-term planning.

Faster Decision Cycles: Integrated commands streamline operational decisions and reduce delays that arise from separate service hierarchies.

International Models

The US Command System: The US employs a global network of geographic and functional combatant commands. This structure supports:

a. Worldwide power projection.

b. Distant expeditionary operations.

c. Differentiated roles for strategic mobility, cyber operations, and global strike.

d. Fully resourced theatres with strategic reserves for enhancing the capability based on operational necessity.

While highly effective for an expeditionary superpower, the US model is resource-intensive backed by economy and rooted in global operations, making it only partially relevant to India.

The Chinese System: China’s 2016 reforms reorganised seven military regions into five theatre commands aligned with major threat directions. Key characteristics include:

a. Large territorial depth and not country specific.

b. Multiple land and maritime fronts demanding operational homogeneity and resource specialisation.

c. Heavy emphasis on jointness and centralised political control.

d. Resources sized for major regional contingencies.

The model reflects China’s continental scale and strategic priorities and differs substantially from India’s more compact geography and resource profile. However, the focus on jointness, operational homogeneity and geography is relevant.

The Indian Context

India’s approach lies between the US and Chinese extremes. The Kargil Review Committee, Naresh Chandra Task Force, and Shekatkar Committee reflect an evolutionary reform philosophy, aimed at preserving institutional balance while improving jointness. India’s theatre command design must be shaped by local realities rather than imported templates. Some major factors are especially important:

Geographical Construct: India’s borders and coastline have distinct character. The northern borders with China are bifurcated into two widely separated entities by Nepal and Bhutan. The advantage of inner lines of communication lies with China. In limited war scenario either entity is unlikely to influence military operations in the other.

Eastern part of India has borders with China, Bangladesh and Myanmar having distinct terrain characteristics. Moreover, all three have antagonistic relations with India. The area, commonly called seven sisters states, is physically connected to the mainland through the narrow and hence strategically important Siliguri corridor.

India’s peninsular shape in the South divides the oceanic region into three regions, Arabian Sea, Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean. While it does not impinge on navigational or operational freedom of navy in the entire region, it does create a divide in terms of time. Andaman & Nicobar Islands, an important cog in India’s maritime dominance, in the Bay of Bengal requires special status in allocation of resources.

Terrain and Operational Homogeneity: India’s land borders involve three distinct operational environments. In the north is the mountainous and high-altitude theatre (Ladakh, and J&K), which entail extreme altitude and logistical constraints. In the east (Arunachal, Northeast and Bangladesh), the challenge of high-altitude mountains is compounded by jungle and riverine theatre entailing extreme altitude, jungle warfare and riverine terrain subject to monsoon effects. The west (Punjab-Rajasthan-Kutch), open and flat terrain is mechanised theatre suited for armour-heavy manoeuvre warfare.

Operational Compactness: Compared to the US or China, India’s geography is comparatively compact, wherein short internal distances, well-developed rail-road networks (especially West) and long ranges of aircrafts give her the advantage of flexibility in force generation.

Cost and Resource Constraints: Theatre commands, logically have to be self-contained with force levels to thwart any threat that emanates from the neighbouring countries. This requires additional resources that will put additional stress on India’s budget. Thus, it is imperative that India streamlines weapons acquisition, joint training and aatmanirbharta.

Current Proposal: The current proposal doing the rounds talks of two land-based commands, Northern (against China) and Western (against Pakistan); one Air and Space Command and one Maritime Command.

JoINtNeSS Rajnath Singh talking to three Service Chiefs along with CDS Gen. Anil Chauhan

Critical Analysis

Given the geographical compactness and the economic constraints, the obvious question that arises is—do we require theatre commands?

Various committees have identified serious deficiencies in joint doctrines, operational planning, intelligence sharing and integrated execution. However, during the 1971 war there was seamless integration between the three services leading to a comprehensive victory over Pakistan over two fronts! The technological advancements since then have revolutionised the battlespace and demands total integrated operations than personality based jointness on display more than five decades ago!

At the same time a question arises—is jointness and integrated operations only possible when there are theatre commands? Is it an outcome of singular authority or other factors have an equal effect on the objective sought? “Jointness is not a structure; it is a state of mind,” said General H. Norman Schwarzkopf. At the same time is there a need to completely overhaul the existing structures or the objective can be achieved by mere tweaking of the current service-based organisations?

Theatres based on Country Threat or Geographical location: The threat scenarios to a country will remain dynamic, the geography will remain constant. “Geography is the fundamental factor in strategy”, American political scientist Nicholas J Spykman had once said. Therefore country-based theatre commands are conceptually flawed! The current proposal violates the principles of geography, homogeneity of operations and logistics. Threat to J&K cannot be fought by two separate commands given its geographical layout, commonality in force availability and logistics. Similarly, a Theatre Command HQs, based in Lucknow, can have negligible value addition to the Eastern front, as Western Theatre Command at Jaipur would have in a limited conflict in Kashmir. The actual execution of operations will fall in the domain of current Army Eastern Command and Northern Command respectively!

WORKING TOGETHER Chief of Defence Staff Gen. Anil Chauhan

at Air Force Station Car Nicobar on January 2;

GOC-in-C Southern

Command, Lt Gen. Dhiraj Seth reviewing the culminating phase of

tri-service Ex Trishul at Madhavpur beach

Threat scenarios: The current geopolitical atmosphere rules out a total war by any country or countries in collusion with each other, especially, nuclear capable states. Therefore, in the future, the threat to India is likely to be in the form of limited wars, albeit a swift one. China is unlikely to get embroiled in war against India when its focus is towards Taiwan and competing with the US for global domination. Instead, it is likely to keep India in check using Pakistan and to some extent Bangladesh. Skirmishes or land grab operations may persist. In the extreme scenario is the threat to Arunachal Pradesh from China, with or without collusivity from Bangladesh in the form of sabotage/ subversion and choking of Siliguri Corridor or to Ladakh, with or without Pakistan. Under such circumstances will the proposed Northern Theatre Command, based in Lucknow, have the freedom or authority to enlarge limited war against China to a full-fledged war by initiating operations in Ladakh/ Himachal/ Uttarakhand or vice-versa? No, because it will fall in the domain of government. If not, then the question arises—what is the role of this command theatre in the operations of existing Eastern Command or Ladakh region of Northern Command?

Organisational Culture: Organisational culture within military headquarters is shaped primarily by the nature and intensity of their operational engagement. Commands that are continuously involved in active operations—such as the Northern and Eastern Commands—develop a decisively operational culture characterised by immediacy in decision-making, situational awareness, and sensitivity to tactical-strategic linkages. Persistent involvement in counter-terrorism, counter-infiltration, and crisis-response activities reinforces a command ethos rooted in realism, adaptability, and responsiveness. In contrast, headquarters whose primary exposure is to peacetime or training-centric functions tend to evolve a more process-driven and deliberative culture. Extending this logic, the establishment of land theatre headquarters located at geographically removed centres such as Jaipur or Lucknow risks creating a command layer that gravitates toward a predominantly theoretical or planning-oriented role, reducing their ability to meaningfully influence time-sensitive operational outcomes.

Operational context: India’s basic philosophy and doctrine is to safeguard the territorial integrity of the country i.e., purely defensive. It is not expansionist in nature. Therefore, the armed forces doctrine relies on building deterrence capability to thwart any threat to its land borders and maritime boundary. Indian Ocean is a seamless battlefield and therefore the stretch of navy needs to extend to cover entire Bay of Bengal, Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean towards south. The area of domination will be entirely dependent on the size of Indian Navy. Security of Andaman & Nicobar Islands is directly linked to the naval operations in the region and needs to be under one authority. Air power, given the short distances has the reach and wherewithal to generate adequate forces in the conflict zone anywhere. With more technological advances in the aerial platforms and speed, accuracy, range of weapon systems, there is limited scope of classic erstwhile air to ground support for the land forces.

Command structures: Creation of new structures will only add to the overheads and therefore a hybrid model of theatre commands needs to be envisaged which will bring in better jointness/ integration without much turmoil in the switchover period. It might be well within the scope of this paper to mention that Service rivalry in the form of promotional prospects or number of commands that each service gets or whether theatre commander will be a four star or three stars, must be set aside to a larger goal of achieving operational effectiveness and efficiency!

Unified Conceptual and Doctrinal Organisation: This is the need of the hour that will look into joint military doctrine. It must keep a tab on the emerging technologies or drive newer technologies and concepts of war fighting in all the likely threat scenarios.

Capability Generation is also an important facet of the overall integrated war fighting. Identification of critical needs, harmonising to each service operational needs will assist in improving cost efficiency. This organisation must facilitate right from identification of weapon systems/ platforms, (design, production/ procurement and maintenance) to communication systems (interoperability) to empowering the forces in application by having common the training establishments and common procedures.

Recommendations

The recommended Theatre Command structure is as follows (see figure below): Three land-based commands namely Eastern, Northern and Western; one Air and Space Command; two Maritime commands that is, Eastern and Western.

Rough Alignment of Theatres Commands

Realignment

(a) Eastern Command to be redesignated as Eastern Theatre Command (ETC). Current Eastern Air Command with all its current assets could be under command of ETC.

(b) Northern Command to Northern Theatre Command with its extent to include plains of J&K and mountainous region of HP and Uttarakhand. Air assets currently deployed in the region could be under command.

(c) Western Theatre Command (Jaipur) to be responsible for Punjab, Rajasthan and Gujarat with only Western Army and Southern Army. Minimal air assets to be in direct support.

(d) Air and Space Command to have all the balance air assets including drones located strategically.

(e) Integrated Air Defence Command with Air Force as the lead agency.

(f) Naval Eastern Command to include A&NC.

(g) Naval Western Command to include Lakshadweep Islands.

(h) Other Organisations under CDS.

(i) An integrated Capability Generation Organisation.

(ii) National Defence University to be the fountainhead of all the conceptual and doctrinal aspects.

(iii) Unified Training with all aspects of aerial combat/aviation under a singular authority of Air Force. Other service specific training could be amalgamated wherever feasible.

The recommendations are based on an evolutionary rather than disruptive reform, consistent with India’s strategic culture and fiscal realities. Such a structure leverages existing command headquarters, preserves terrain-specific operational expertise, maintains logistical compactness, and enables jointness without excessive duplication of resources.

Conclusion

India’s deliberations on theatre commands reflect a broader transformation in the character of warfare and the growing recognition that future conflicts will demand seamless integration across domains, services, and decision-making levels. A careful analysis of India’s geographical realities, operational environments, and resource constraints reveals that the effectiveness of theatre commands depends less on their numerical count and more on their coherence, compactness, and alignment with terrain and threat vectors.

Combining dissimilar theatres under expansive, country-centric commands risks diluting specialisation, complicating logistics, and increasing command friction without delivering commensurate operational benefits. The current proposal for two land-based theatre commands, structured primarily around perceived adversaries, raises significant conceptual and practical concerns.

Ultimately, the success of theatre commands will depend not merely on organisational charts but on unified doctrine, integrated capability development, joint training, and a shared operational vision across the Services. Theatre commands must be instruments of combat effectiveness, not symbols of reform. If designed with clarity of purpose and grounded in India’s unique strategic context, they can significantly enhance the nation’s ability to deter conflict, respond decisively when required, and safeguard its territorial integrity in an increasingly contested security environment.

Subscribe To Force

Fuel Fearless Journalism with Your Yearly Subscription

SUBSCRIBE NOW

We don’t tell you how to do your job…

But we put the environment in which you do your job in perspective, so that when you step out you do so with the complete picture.