Only a political resolution can help curb radicalisation

Ghazala Wahab

Srinagar: As dusk settled in, the call of the muezzin broke through the cacophony of the traffic and surge of people rushing to reach a place where they could break their daily fast. On the bustling streets of Residency Road leading up to the famous (or notorious, depending upon one’s perspective and memories) Lal Chowk, men, and sometimes boys, stood on the pavement with trays of milky drinks and dates for the passing rozgaars (those who were on the fast) who were unlikely to reach their home or a mosque in time.

Yet, not everybody heeded the muezzin’s appeal. Many held out. A few minutes later, another muezzin cried out, urging the devotees to break their fast and come to the mosque for the maghrib (dusk) prayers. Before this azaan could be finished, another one broke out and then yet another. For a brief moment, suspended in time, it seemed that there was an open-air surround sound system, with azaans in various stages of recitation reverberating in the atmosphere.

It was not the truancy of the clocks that led to the difference in the timing of the muezzin’s call. It was the difference amongst the various sects that have sprouted in Kashmir, which determine their own timings, always at variance with others.

Of course, there has always been a variation in prayer timing and mosques amongst the Muslims, since the division of the community into Sunnis and Shias, but in today’s Kashmir, there are sectional mosques with their own prayer time even within the majority Sunni community. From the erstwhile Jamaat-e-Islami to the gradual sprouting of sects like Ahl-e-Hadis, Ahl-e-Sunnat dawat e Islam, Saut-ul-Haq among others, there are innumerable numbers of sects operating their own mosques and madrassas in the Valley. While some like Ahl-e-Hadis have a following running into a few hundred thousand including a number of medical and educational institutions (it’s proposed Islamic university with affiliation to Medina University was approved during Ghulam Nabi Azad’s chief-ministership), there are many which are restricted to a few districts alone and hence function (for good or bad) well below the radar screen.

One wonders if the former director, Intelligence Bureau and now government’s special envoy for counter insurgency (CI) and extremism, Asif Ibrahim (whose religion unfortunately became his calling card) paid attention to the mushrooming of sectional mosques and azaans in Kashmir during his recent visit (second week of July) to assess the extent of radicalisation in the Valley. He was accompanied by the current director IB, Dineshwar Sharma. A few days later, national security advisor, Ajit Doval, also visited Srinagar and met the same set of people: governor, chief minister, 15 Corps commander, director general police, J&K, inspector general police Kashmir zone and IGP CID. Perhaps, the special envoy and director IB missed something that the NSA, an expert in covert operations, sought.

The immediate provocation for these visits has been the waving of the ISIS flags in various parts of the Valley amidst fears that more local boys are taking up arms now than they did in the last few years. Even though rational voices have pointed out that the ISIS flag has been waved only as a red rag to the government, just as there used to be sloganeering about al Qaeda once upon a time, the Union government is being extra cautious. Clearly, it is not oblivious to the reports of growing radicalisation amongst the youth in Kashmir.

Yet, despite its caution, the possibility of the government making the wrong assessment is high; safe to add, as always. It is talking to the wrong people. And it is relying on reports and statistics sent by field officers instead of local residents with no axe to grind. The field officers, whether in the intelligence bureau or the state police, are unlikely to furnish very reliable figures for two reasons. One, they wouldn’t care to distinguish between fundamentalism and radicalisation because they have not been taught to do so. Two, their priority is to show good results to their bosses, as their promotion depends upon it. Whether the society is transforming for good or bad is the least of their concerns. And if they admit that a greater number of boys from their area have joined militancy, it will add nothing to their CV. Best to leave that to their successors.

Kashmiris of all hues, from government officials to Separatist politicians, admit that their society has changed; and not for the good. However, the degree of admission varies. One of the young spokesperson of the National Conference speaking on the condition that he would not be quoted says, “Radicalisation is not a Kashmir-specific problem. A certain percentage of Muslims worldwide are getting radicalised. Maybe the number in Kashmir is higher than that in Delhi.”

President of the youth wing of the ruling People’s Democratic Party (PDP) and political analyst in chief minister Mufti Mohammed Sayeed’s office, Wahid ur Rehman Parra says, “There is a growing trend of radicalisation and desire for pan-Islamism amongst the youth.”

Even the Separatist philosopher-politician Professor Abdul Ghani Bhat says, “Of course, there is radicalisation. But don’t ask me for the solution. This is a problem created by you (alluding to the Government of India) and only you can resolve it.”

The nuances of admission notwithstanding, the change is evident in the state. Not only in the multiple calls of the muezzin for the same prayer, but in the way people dress and behave; in the emergence of completely alien male headgears, in head-to-toe veils that women wear and in the increasing desire of the parents to entrust their children to madrassas for religious learning instead of trusting their own knowledge. Very few in Kashmir are unaffected by the increased religiosity and to some extent fundamentalism.

A few years ago, a Kashmiri man working in one of the vineyards of western India returned home on a visit. He was told by some people in his community that his job was un-Islamic because the grapes that he helped cultivate were eventually used to make wine, a forbidden drink. The man sought religious opinion (fatwa) and was told that if he can ensure that the grapes that he grew were not pressed into wine he could continue with his job, otherwise he must quit. He quit. As atonement, he grew a beard and is now amongst thousands of underemployed Kashmiris in the state with too much time on his hands and too little work, relying on the family business which already feeds far too many people.

In another instance, one of the regular drivers that FORCE hires when in Kashmir is an elderly man, well in his 60s. A dapper dresser, with not a trace of facial hair, he plays romantic songs from the Hindi films of the Fifties and Sixties in his taxi and keeps a friendly distance from every day prayers. He shrugs when asked about his faith.

“Who knows what will happen,’ he says with a sheepish smile. “The only certainty is that we have one life.”

Yet, his own son has turned his back to his father’s philosophy. While still in school, he joined Ahl-e-Hadees. Today, a press photographer in his late 20s, he has a full grown beard and never misses his prayers, no matter where he is. He frequently chides his father for what he considers his wayward manners.

“I am happy that he has chosen the religious path,” says the father. “Given the situation here, he could have gone any other way. So, I don’t mind when he tells me that I should mend my ways and pray more often. At least, he is here with me to tell me all this.”

These are not radical people, only hugely insecure individuals, rendered thus, perhaps by the political environment in which they find themselves, who have entrusted their judgement to the so-called religious wise men. And here lies the danger. The process of radicalisation does not happen in isolation. It needs a mind made supple by religious indoctrination to take roots. The first step is always obsessive commitment to fundamentals of the religion and blind faith in the local preacher. The second step is the cause that cultivates and fans the sense of injustice. Innumerable examples of this exist in the case studies of young men in different European states who wake up one day to enrol themselves for jihad, earlier in Afghanistan and now in Iraq and Syria.

The biggest mistake that the West has made in addressing the issue of radicalisation is to dismiss the notion of cause and effect. It is almost impossible for a person, with the promise of a fulfilling life ahead, to choose death without a cause. Since we usually emulate the West, we are making the same mistake in Kashmir; dismissing insurgents as either misguided youth or denouncing them as terrorists, as if they are operating completely without a cause.

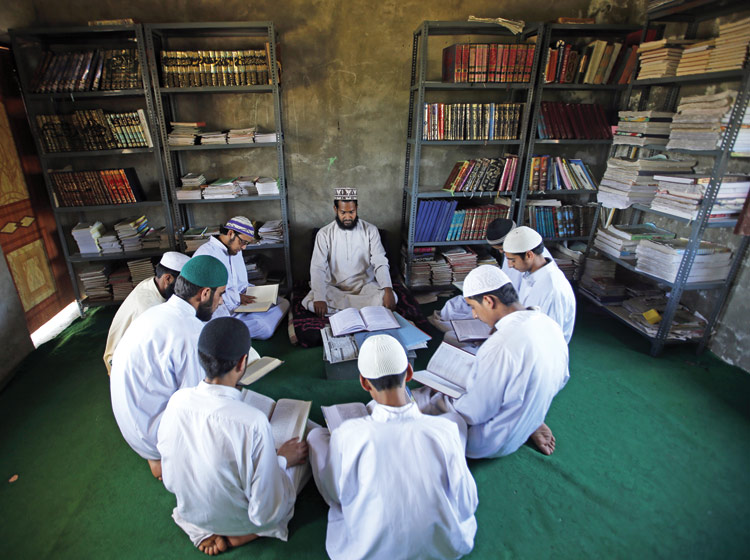

For the burgeoning youth of Kashmir, the cause was always there. Now it is being nurtured through careful religious indoctrination. “In the last 20 years, madrassas have mushroomed all over the state. Most of them are one-room tenements,” says a middle level police officer posted in south Kashmir. According to him, there is no accounting of their funding or syllabi, despite the fact that everyone knows that money comes from West Asia, especially Saudi Arabia. “The successive state governments have had a hands-off approach, saying that since they do not take any money from the state, the government has no control over them. But in the interest of the future of the state, some sort of auditing must be carried out of these madrassas.”

Posted in the part of the Valley which has had the highest number of youth in recent times to pick up gun, the police officer has done his homework. This year 65 boys from south Kashmir have joined militancy. And with the exception of one police constable, the rest are all young semi-educated, unemployed boys with an obsessive commitment towards ritualistic religion. Needless to say, their favourite haunts were the mosques.

While Islam maybe the religion which emphasises upon the unity and indivisibility of Allah, in just a few years after the death of its founding and the last prophet, Mohammed, the Ummat (community of his followers) started to disagree on almost everything beyond the five basic pillars of the religion.

In the following centuries as Islam spread rapidly, well beyond the imagination of its earliest members, sundry wise men emerged in various parts of the world to help the neo-converts understand the religion they had chosen to follow, and also to navigate them through the treacherous journey that the life of a Muslim probably is (given all-round temptations). The earliest sects (Sunni and Shia) continued to mutate over the centuries with each newer sect becoming holier (and righteous) than the earlier one, with the exception of the Sufi branch of Islam, which propounded inclusiveness and selfless love towards god.

Unlike the Wahhabi and Salafi sects (of Sunnis), which instil the fear of hell and the lure of paradise amongst the adherents, Sufism preached the love of god, with the Sufis regarding god as almost a beloved. Since the faith emanated from selfless love, its list of ‘don’ts’ was limited; whether it was music or falling in a trance or spending one’s life at the tomb of a saint, practices abhorred by the puritans of Wahhabi or Salafi denominations.

In India, Islam arrived in all its various permutations and combinations. However, in Kashmir, it was the Sufi strand of Islam which found fertile grounds, primarily because the Sufis rejected little and embraced everything. The so-called syncretism of Kashmir or Kashmiriyat emanated primarily from the Sufi thought, which combined metaphysics with the religious. There was no conflict in co-existence with other faiths and practices despite the fact that Kashmir, as a society, was deeply religious, whichever be the religion. Even when revisionist or what is referred to as reformist Islam swept through the world, including parts of India, in Kashmir it could not make much of a mark.

However, 26 years of exposure to violence changed all that. While in absolute terms, Sufism may still be the dominant strain of Islam in Kashmir, newer and more exclusivist sects have emerged as the favourite of the young. There are many reasons for that.

One, the puritan sects demand little intellectual investment from their followers. All they ask is absolute and complete adherence to their interpretation of the Quran and the Hadith (compilations of habits, sayings and traditions of Prophet Mohammed, as remembered or understood by his successors). Today, there are so many Hadiths, quite a few compiled by people even two generations removed from Prophet Mohammed that even contradictory injunctions can be justified quoting some obscure text. Even the ones which can be rightfully attributed to the Prophet were relevant in the context they were said or occurred. They can’t be held as truism under all circumstances.

Two, with the long list of proscribed behaviour, they make following the religious path very arduous for the followers, leading to the feeling that they are on the right path. After all, isn’t the righteous path more difficult? This is something akin to performing a pilgrimage on a daily basis. Moreover, this makes one aspire for paradise even more fervently.

Three, an increasing number of young people are technology-savvy. A technical mind prefers a simplistic religion with clear-cut tasks and goals. The amorphous, informal and all-encompassing Sufi thinking simply does not offer anything on the platter. It urges each individual to plod his or her own path. This is also the reason why the easiest people to get radicalised have technical background in terms of education. Their minds are already trained to learn and execute formulas and equations.

The biggest concern here is that the youth which is relentlessly exposed to such a puritan form of religion ceases the habit of independent thinking and becomes susceptible to indoctrination. Moreover, puritan by definition implies intolerance for dissent and different viewpoints. Since the puritan is convinced that only he is on the right path, he has only two choices. Either get others onto your path through proselytising (Dawah) or simply shun them. It is also not difficult to justify to oneself that since the others are already doomed in the hereafter; their fate in this world is of little consequence. Religious violence is just the next step.

While this is universally applicable, for us, this is the most worrying reality of Kashmir today, because the failure to resolve the Kashmir issue has now ladled-in religious extremism into the already churning cauldron of political discontent. The insurgency exposed the Kashmiri to foreign forms of puritan Islam which disparaged the indigenous and inclusive religion followed by the locals.

As the offshoots of so-called Wahhabi/ Salafi line of Islam started to grow roots in Kashmir, the Government of India, ever short of ideas, decided to inject moderate form of Islamic sects in the state to counter the Saudi import via Pakistan. So, not only was the Government of India subverting the political process in the state, it started to subvert faith too! According to the locals, the Ahl-e-Sunnat dawat e Islam sect (derivative of Barelvi sect) has been New Delhi’s gift to Kashmir.

Basically, in 2010-2011, there were a few incidents of sectarian violence in Kashmir, even though there weren’t any casualties. But the mischievous nature of violence —desecration of Quran, destruction of the pulpit in a Shia mosque and even targeted killing of the head of Ahl-e-Hadis, Kashmir, Maulana Shaukat — led the government in Delhi to think that religious hard-liners would create a Pakistan-like situation in Kashmir. Moreover, there were reports that some form of Tehreek-e-Taliban Kashmir has been established in the Valley and it was busy recruiting boys in the rural areas.

Hence, the Government of India started dabbling in religion, encouraging and financing what it thought would be moderate sects. It failed to foresee that even a moderate sect, is a sect nevertheless. To increase its base and to keep its flock from wandering over to a different sect, it has to perforce preach intolerance of other sects. Imagine a society, divided into religious communities of a few hundred thousand, each convinced that only it is right. What does it portend?

It may appear to be far-fetched at the moment, but Kashmiri youth today is extremely vulnerable and susceptible to radicalisation. The armed insurgency is in its 27th year. Everyone in Kashmir below the age of 26 has seen nothing but violence, curfew, cordon and search operations, humiliation, uncertainty… and a largely exclusive Muslim society, which has increasingly been seeking succour in religion. Their entertainment avenues are limited to spending time at mosques or playing cricket/ football in one of several graveyards dotting the state, provided there is no curfew or crackdown that day.

“Every home in Kashmir is a monument of history today,” says Bhat. “When strangers meet, they ask each other, ‘brother, how many have you lost?’ referring to family members killed in militancy.”

To top it, for the middle and lower middle class majority, the future holds no promise. Neither of peace, nor a career that meets their aspirations. “Everyone wants a government job, even if it doesn’t pay much. But how many jobs can the government generate,” says Parra. This explains the spectacle of graduates and post-graduates queuing up at army’s and paramilitary’s recruitment rallies which demand the minimum qualification of only class 10. This also explains why most of the boys who have recently taken to arms are educated, at least till the school level if not more.

“There is a qualitative difference in the militancy today,” says human rights lawyer Parvez Imroz. “In the mid-Nineties, lumpen elements had joined the movement. While this added to the numbers, it diminished the quality. Now the boys are better educated and more radicalised.”

They are also technologically sound. They are able to create temporary communication applications on the mobile phones, in addition to using multiple internet-based systems with portals located in different countries. According to the unnamed police officer, “It is not possible to intercept these. As a result, our capacity to generate technical intelligence has been severely compromised.”

They are also technologically sound. They are able to create temporary communication applications on the mobile phones, in addition to using multiple internet-based systems with portals located in different countries. According to the unnamed police officer, “It is not possible to intercept these. As a result, our capacity to generate technical intelligence has been severely compromised.”

Human intelligence also has its limitations, given that the newer batches of militants are not crossing the Line of Control (LC) for training. They are doing it within the state; and posting pictures on social media, without anybody reporting their whereabouts.

Statistics, a favourite tool of the government to present the reality as it likes it, are not enough to assume the turn Kashmiri society, and thereby the Kashmir issue, will take in the next few years. While the police officer, judging by his area of operations says, “The year 2017 is going to be very bad because a lot of factors are going to converge,” people like Imroz are worried about the society that Kashmir is turning into.

“Our institutions have repeatedly failed the citizens. Even if everything is put in order by a magic wand someday, what are we going to do with the people — this alienated, disillusioned, despairing mass? What kind of Kashmir are they going to build even if given a chance?,” he asks plaintively.

Political resolution will not reverse the tide of radicalisation, but it will certainly arrest it. Because hopefully the resolution will open diverse economic avenues for the young and foreclose the option of the gun. That’s something to hope for.