Prisoners of History

Brig. B.L. Poonia (Retd)

Tibet was a part of China since 1720, under

the control of Quing dynasty. The sudden collapse of Chinese power in Tibet in

1911-12, tempted Lord Hardinge to capture the area which later came to be known

as North East Frontier Agency (NEFA). Since a direct attack on Tibet would have

resulted in a war with China, Britain convened a ‘Tripartite Conference’ in

Simla, comprising Britain, China and Tibet in October 1913. Even during this

period, China exercised ‘suzerainty’ over Tibet, i.e. it controlled Tibet’s

foreign policy, since Tibet did not enjoy independent treaty making powers.

Tibet was a part of China since 1720, under

the control of Quing dynasty. The sudden collapse of Chinese power in Tibet in

1911-12, tempted Lord Hardinge to capture the area which later came to be known

as North East Frontier Agency (NEFA). Since a direct attack on Tibet would have

resulted in a war with China, Britain convened a ‘Tripartite Conference’ in

Simla, comprising Britain, China and Tibet in October 1913. Even during this

period, China exercised ‘suzerainty’ over Tibet, i.e. it controlled Tibet’s

foreign policy, since Tibet did not enjoy independent treaty making powers.

However, the Simla Conference did not

result in any treaty, since China rejected the British proposal of McMahon

Line. Hence, the British secretly signed a ‘Bilateral Agreement’ with Tibet,

assuring it all the help in getting independence from China. But interestingly,

even the ‘1913 Simla Convention’ showed Aksai Chin as part of Tibet.

As I wrote earlier (FORCE, December 2024), W.H. Johnson, a British officer of Survey of India, who visited Khotan (China) in 1865 via Aksai Chin, drew a boundary line showing Aksai Chin in Kashmir territory. It was named ‘Johnson Line’, and the same was published in an Atlas in 1868. However, it had no legal sanctity, since it was a unilaterally drawn line that was sought to be proposed, but the British never even communicated this as a boundary proposal to China. Interestingly, this is the line from which India derives its claim on Aksai Chin.

While the British did mark Johnson

Line on its maps, it did so only after depicting its legal status as ‘Boundary

Undefined’, and not as an international border. Moreover, the British never

laid any claim on Aksai Chin till their departure from India in 1947. In fact,

in 1899 the British made ‘McCartney-MacDonald Boundary Proposal’ to China,

suggesting inclusion of a small portion of Aksai Chin in British territory, to

which China never replied. After 1899, there was no further attempt by the

British to get China to agree to a boundary alignment across Ladakh. Hence,

Aksai Chin continued to remain part of China.

Coming back to the Simla Convention, four months later, the British invited Tibet to Delhi for further discussions on Assam-Tibet border in February-March 1914. China was neither invited, nor informed, yet a secret treaty was signed on 24 March 1914, and the alignment agreed upon was McMahon Line, which implied making NEFA a part of British territory. But this treaty was kept secret for the next 23 years, since it was in violation of Anglo-Chinese Convention of 1906, as well as Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907, under which Britain was prohibited to enter into negotiations directly with Tibet except through an intermediary of the Chinese government. When China learnt about the secret treaty, it repeatedly announced that it would not recognise any treaty, of which China was not a part.

In short, it was an illegal treaty. Had it been legal, Britain would have occupied NEFA in 1914 only. No wonder, the British did not even publish the McMahon Line on its maps for the next 23 years. Survey of India published it only in 1937, that too by depicting its legal status as ‘Boundary Undemarcated’. Moreover, the British never made any attempt to annex NEFA, and NEFA continued to remain a part of China even after the British left India in 1947. This implied that even independent India had no legal right to occupy NEFA, without the consent of China.

After

Independence

While the Chinese power returned in Tibet in

1950, it soon got occupied with the Korean War (1950-1953). It was during this

period, that India quietly annexed NEFA in 1951 by sending a strong patrol

under Maj. Bob Khating of Assam Rifles, who hoisted the Indian flag at Tawang

on 9 February 1951, forcing the Tibetan administration out, in spite of its

vehement protests. Thus McMahon Line was ‘unilaterally’ transported from the maps

to the ground as the de facto north-east boundary of India. China maintained a

puzzling silence, since it still wanted to maintain good relations with India,

but Nehru misconstrued China’s silence as its military weakness.

By annexing NEFA, India added 65,000

sq kms of territory, which legally belonged to China. Hence NEFA (now Arunachal

Pradesh) belongs to India only on the basis of the ‘Right of Possession’ and

not on the basis of any legitimate treaty. And that precisely is the reason why

China continues to lay its claim on Arunachal Pradesh till date. The same goes

for Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (POK), which is held by Pakistan only on the

basis of the ‘Right of Possession,’ and not on the basis of any treaty, hence

India exercises a legitimate claim on POK. Legitimacy of claim cannot be

overlooked however old the issue might be. In fact, POK is an issue, older than

NEFA.

In its quest to maintain cordial

relations with India, while China maintained a studied silence over the

unilateral annexation of NEFA, it did feel deeply hurt. Chinese foreign

minister, Chen Yi openly expressed this in September 1959, when he said, “In

attempting to impose the McMahon Line on China, India had not given the

slightest consideration to the sense of national pride and self-respect of the

Chinese people.”

Unilateral

Revision of Boundary Lines

On 29 April 1954, India and China signed the

Panchsheel Treaty, which underscored five principles for peaceful co-existence.

The slogan ‘Hindi-Chini Bhai-Bhai’ became very famous during the mid-Fifties.

But Nehru considered China militarily a weak nation, incapable of facing India;

a belief which resulted in India adopting ‘Forward Policy’, leading to 1962

debacle.

According to A.G. Noorani’s book India-China Boundary Problem 1846-1947:

History and Diplomacy, even a month before Nehru signed the Panchsheel

Treaty, he had already embarked upon an ambitious ‘top secret’ mission, without

taking into confidence any of his cabinet colleagues, to revise and amend the

Indo-China boundary lines unilaterally on Indian maps, vide an exercise which

commenced on March 24 and completed on 30 June 1954.

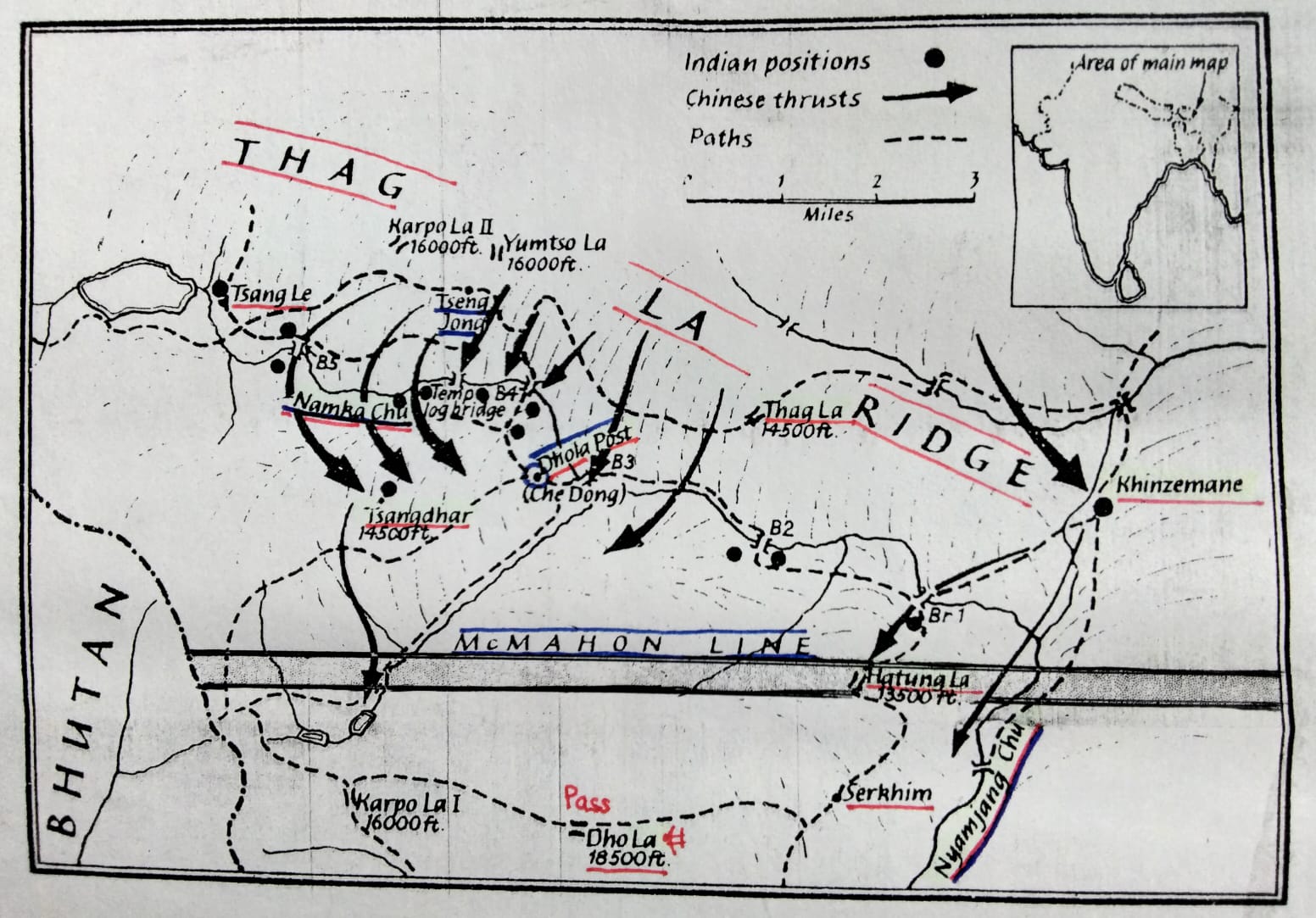

During this exercise, he removed the legal status of Aksai Chin boundary, originally marked as Johnson Line (Boundary Undefined), and NEFA boundary, originally marked as McMahon Line (Boundary Undemarcated), and converted these as clear international borders on the maps. He did this even though, neither can the legal status of international boundaries be removed or changed, nor can the alignment of boundary lines be altered, unilaterally. Another significant change made by Nehru was to alter the alignment of McMahon Line in the Kameng Frontier Division of NEFA, shifting it further north from Hathung la Ridge to Thag la Ridge, involving a unilateral shift of about five kilometres, thereby including around 100 square kilometres of Chinese territory in India. The importance of Thag la Ridge lay in the fact that it provided an unhindered view of the Chinese movements and military build-up, deep inside its territory. Thus, Indian maps started showing Aksai Chin, NEFA, and Thag la Ridge (16,000 ft) as part of India, in utter violation of international treaties. More importantly, it was a breach of faith with China, and this is the root cause of Indo-China border dispute.

Noorani’s book mentions that Nehru

wanted these maps to be sent to embassies abroad. He also introduced the same

to the public in general, to be used in schools and colleges. Accordingly, new

maps and atlases were printed showing Aksai Chin, NEFA and Thag la Ridge in

Indian territory, with clear international borders. The Indian youth which grew

up seeing these borders on maps since 1954, had no reasons to doubt or

disbelieve, hence these got etched in stone.

Noorani writes that even the 1950

edition of Indian maps showed the correct legal status of Johnson and McMahon

Lines, and correct boundary alignment of Thag la Ridge. He writes, “A century

old problem was neglected by a conscious decision in 1954, which in turn

acquired the dimensions of boundary dispute in 1959. Unresolved in 1960 when

the prospects of a fair settlement were bright, the dispute was sought to be

resolved by confrontation.”

He further writes, “The conclusion is

hard to resist that there was a total disconnect between the facts of history

and India’s policy on boundary problem, and later boundary dispute, and worst

of all, an impermissible recourse to unilateral change of frontiers.” It

flouted the 122-year old October 1842 Treaty of Chushul. Even the US’s secret

‘CIA Papers’ confirmed these facts. Thus, Nehru shut the doors to boundary

negotiations on 1 July 1954.

The only eyewitness to this ‘top secret’ mission was a junior Indian foreign service official named Ram Chandra Sathe, who later rose to become India’s Ambassador to China, and retired as foreign secretary on 30 April 1982.

VIDEO

VIDEO