Mind Over Matter | Battling the Forbidding Water Woes

Maj. Gen. Mrinal Suman (retd)

Maj. Gen. Mrinal Suman (retd)

113 Engineer Regiment located at Jodhpur was assigned the task of sinking two 600 feet deep shafts in the Pokhran Ranges for testing a 45 kt fusion bomb (also called hydrogen or thermonuclear bomb) and a 15 kt fission bomb (atomic bomb). The shafts were dug in 1981-82. Due to international pressure, the tests had to be deferred. However, regular maintenance of the shafts was carried out by different regiments till Pokhran II took place in May 1998.

For 113 Engineer Regiment, it was an unprecedented assignment. To sink shafts hundreds of feet deep was a huge challenge — more so as none of the officers had ever seen a shaft or visited a mine; nor had anyone studied mining engineering which is a specialised course.

A word about shaft sinking will be in order here. To approach underground mineral seams, a vertical opening (shaft) is provided from the surface to the mining zone. These shafts are used to carry men, material and equipment to the mining zone; as also, to haul the extracted ore to the surface. Being the lifelines of all underground mines, shafts are sunk with exacting technical specifications. Every mining manual terms shaft sinking to be the most dangerous and hazardous task. It requires domain expertise and specialised equipment. There are a handful of shaft sinking companies in the world, normally called ‘sinkers’. All mining companies outsource shaft sinking operations to them.

The late Lt Col K.C. Dhingra (later rose to the rank of Major General) was the commanding officer of the regiment. Two task forces were constituted and the work started at the selected sites in February 1981 without much fanfare. After having cleared the sand over-burden, we encountered a conglomerate consisting of gravel, sandstone and silt stone. Digging was tough as the drill used to get stalled in the bores. We also encountered shale, a fine-grained clastic sedimentary rock. It is a mudstone that is fissile and laminated. After every 10 feet of depth, we had to pause to stabilise the shaft walls with steel jackets and rock-bolts.

Water seepage was first encountered at 60 feet depth. Although the quantity of inflow was limited, it still posed problems in digging. Water had to be collected in a sump and pumped out at intervals. Initially, we used pumping sets of our regimental water supply equipment, but soon found them to be unsuitable due to limited delivery head.

A few sump pumps were procured from the market. The work on shaft digging continued for some time. As the sump pumps need 220 volt electric power, they could be used only after getting all the men out, lest they get electrocuted. The progress became unacceptably slow as frequent movement of men (in and out of the shaft) wasted considerable time.

As we dug down, difficulties increased. At about 100 feet depth, water ingress increased substantially. Within an hour, water level used to rise to five-six feet. Drilling became impossible. We realised that dewatering had to be done concurrently with drilling and mucking (removal of blasted earth/rock). Consequently, all electric devices (including submersible pumps) got ruled out. As the water inflow became unmanageable, work at both the shafts came to a halt. Ghosts of Pokhran-I (the incomplete shaft had to be abandoned due to water woes) started haunting us.

It was a nightmarish situation. Water had indeed posed a major challenge that appeared to defy all solutions. Though we were at a loss for a while, we were determined not to let the country down. But the soldiers of 113 Engineer Regiment are not ‘quitters’. They never give up. After some brain-storming, we decided to learn about the methodology of dewatering, as followed by the professional shaft sinkers. For that, we needed to visit a few mines.

Col Dhingra convinced the authorities and permission was received to visit Khetri copper mines

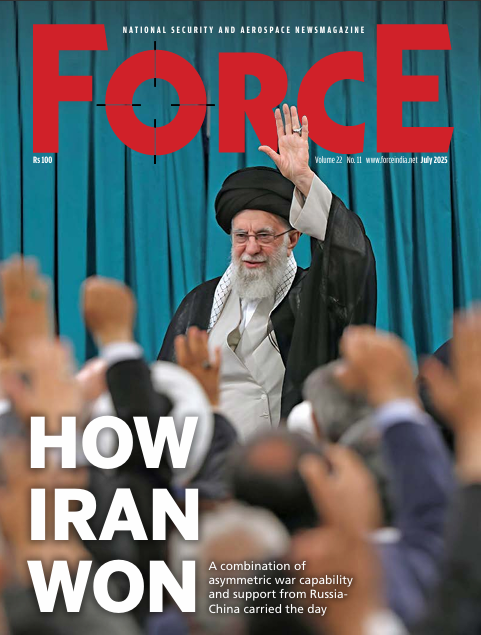

Subscribe To Force

Fuel Fearless Journalism with Your Yearly Subscription

SUBSCRIBE NOW

We don’t tell you how to do your job…

But we put the environment in which you do your job in perspective, so that when you step out you do so with the complete picture.