Hard Bargain

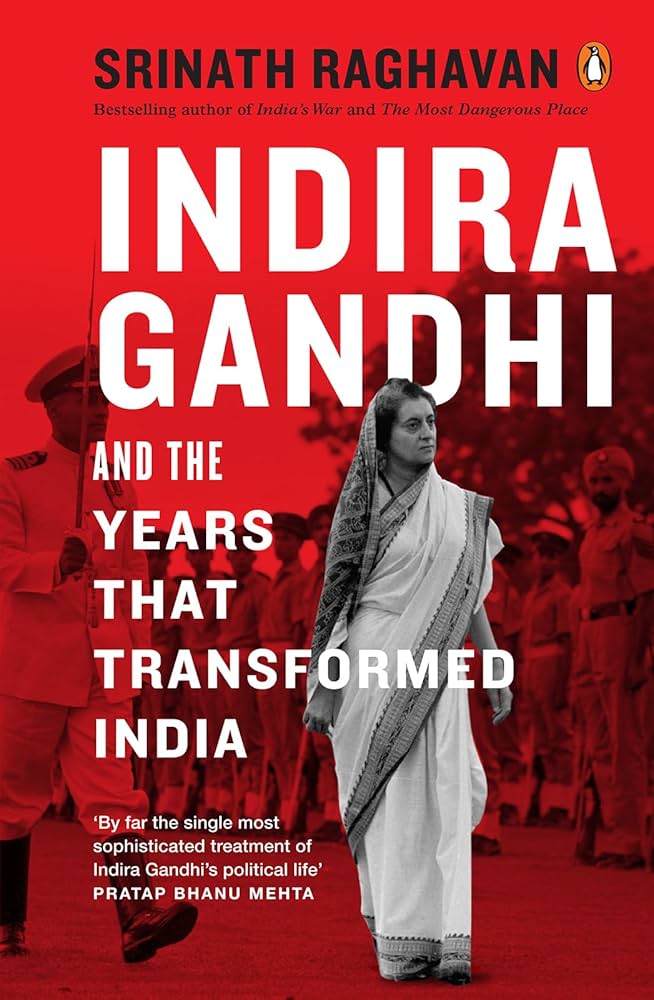

Indeed, these

elections were very like a popular acclamation of Indira Gandhi’s leadership.

The Congress party swept all the states. As P.N. Dhar conceded, this stunning

outcome was “a gift of the victory in the Bangladesh war; they were truly khaki

elections.” The political landscape was scythed clean of rivals and opponents.

The opposition parties were at once undone and unnerved.

Indeed, these

elections were very like a popular acclamation of Indira Gandhi’s leadership.

The Congress party swept all the states. As P.N. Dhar conceded, this stunning

outcome was “a gift of the victory in the Bangladesh war; they were truly khaki

elections.” The political landscape was scythed clean of rivals and opponents.

The opposition parties were at once undone and unnerved.

The postwar

conference in Shimla showed her capable of managing the peace as well as

winning the war. Indira Gandhi was persuaded by Haksar not to impose a punitive

peace on Pakistan. Had the Treaty of Versailles, he observed, “not imposed upon

Germany humiliating terms of peace, not only the rise of Nazism would have been

avoided but also the seeds of the Second World War would not have been sown.”

In consequence, the prime minister refrained from pushing President Z.A. Bhutto

for a final settlement on Jammu and Kashmir. Instead, she sought the conversion

of the extant ceasefire line (from 1949) into a “line of control”, as well as a

commitment to settle disputes bilaterally and to avoid using force. The prime

minister was averse to making the ceasefire line the permanent international

border because she did not want to be seen as giving up territory that India

formally claimed. She was content for the line of control gradually to acquire

“the characteristics” of a peaceful international border.

The victory against Pakistan and the Shimla agreement also strengthened Indira Gandhi’s hand in dealing with the knottiest problem in Indian politics: Jammu and Kashmir. India’s only Muslim-majority state had acceded to the union under dramatic circumstances months after partition in 1947. Nehru had regarded this as an affirmation of India’s secular identity and had sought to forge a close rel

Subscribe To Force

Fuel Fearless Journalism with Your Yearly Subscription

SUBSCRIBE NOW

We don’t tell you how to do your job…

But we put the environment in which you do your job in perspective, so that when you step out you do so with the complete picture.

VIDEO

VIDEO