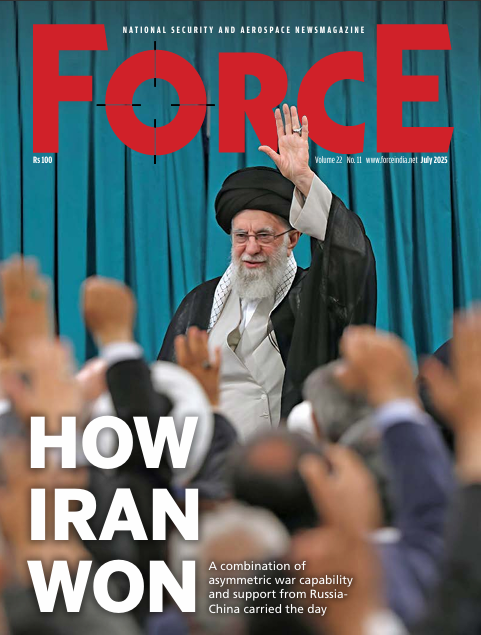

First Person | Ruse of the Reforms

Ghazala Wahab

Ghazala Wahab

Two compulsions and one assumption steered the government towards the Agnipath recruitment scheme. The compulsions first.

In 2013, once Narendra Modi was declared Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) prime ministerial candidate, he addressed an ex-servicemen rally in Rewari accompanied by the former army chief and by then a BJP politician, Gen. V.K. Singh. He assured the exultant crowd that once he came to power, he would favourably resolve the One Rank One Pension (OROP) issue that had been exercising the armed forces personnel. Thereafter, the BJP election manifesto promised implementation of OROP.

The problem with the promise was that the scheme made no economic sense. That was the reason the previous government, despite repeated assurances, could not implement it. In a move to placate the protesting ex-servicemen, the UPA government did increase the old pensions in a manner that the gap between them and the current was significantly reduced. But it refused to equalise the pensions in perpetuity, between, say, a colonel who retired in 1990 and the one who retired in 2010. The logic was that a person’s pension depended upon the salary he/ she drew upon retirement and not what that salary would be 20 years later.

But once the BJP chose populism over logic, it had to fulfil its promise, which it did in November 2015. Sure enough, defence allocations shot through the roof. A brief pause, to understand the nuances of the defence budget. The defence budget is divided between the revenue and the capital. The revenue is for pay and pensions; and the capital is for the purchase of defence equipment, basically modernisation of the forces. Even before the implementation of the OROP, the ratio between the revenue and the capital allocations was skewed in favour of the former.

However, with the OROP imposing a recurring expenditure of nearly Rs 7,123 crore every year, the total spending on pay and pensions crossed 70 per cent of the total spending on defence, leaving even less money for buying new equipment. Worse, the remaining 30 per cent is not available for buying new stuff alone. It also has to cater for instalments on the already bought weapon platforms. Now, if the economy was growing at 10 per cent, as once we thought it would, this expenditure wouldn’t have hurt so much. But given the way things are and are likely to be in the foreseeable future, claims of USD 5 trillion economy notwithstanding, it is impossible for the government to meet this expenditure.

In 2019, former military advisor to the National Security Advisor Shiv Shankar Menon, Lt Gen. Prakash Menon and deputy director of Takshila Institution Pranay Kotasthane wrote a paper on ‘A Human Capital Investment Model for India’s National Security System’ in which they proposed several measures to contain the growing burden of defence pensions. Though not officially accepted, the Agnipath scheme is loosely based on their tour of duty (ToD) model. One major difference is that while ToD included officer cadre as well, the Agnipath is limited to jawans.

So, anyone who says that Agnipath is about reforms is either ignorant or a liar. It is only about money. Simply put, we don’t have any. A testimony to this is the carcasses of innumerable procurement programmes which the ministry of defence has been stalling for years on some pretext or the other. All kinds of theoretical changes in the procurement procedure have happened, including renaming—from defence procurement procedure (DPP) to defence acquisition procedure (DAP)—yet neither the Indian industry has been able to produce anything, nor have we been able to buy the critical equipment that the services wanted through global tendering for want of money.

Take two cases for example, the fighter planes for the Indian Air Force and the submarines for the Indian Navy. A simple Google search would throw up the chronology, so I won't waste valuable space on that. Given where we are on these programmes today, even if we are able to conclude one of these tenders soon, say, the 114-fighters for the IAF, by the time we will be able to induct them, the technology would have become near obsolete. The IAF has been seeking a 4th Generation plus fighter for the last decade and half. The US and Russia are already operating the 5th Generation fighters. Even China has a 5th Gen fighter now, which is likely to find its way to Pakistan Air Force too. What’s more, the Americans and the Europeans have proven technology of fighters flying in concert with unmanned flying vehicles, whereby the capabilities of the manned fighters would be multiplied by the accompanying unmanned aerial vehicles referred to as the loyal wingman. Of course, several countries, including Russia and China already have the capability of unmanned vehicles to carry out aerial strikes, which they envisage will replace the need for human fighter pilots in the future.

Hence, the criticality of MoD taking serious and sustained interest in defence modernisation, whether through indigenous research and development or partnership with foreign companies cannot be overemphasised. And this can only be done if there is money for long-term investment.

The second compulsion was China’s sauntering in into Indian territory in Ladakh in April 2020

Subscribe To Force

Fuel Fearless Journalism with Your Yearly Subscription

SUBSCRIBE NOW

We don’t tell you how to do your job…

But we put the environment in which you do your job in perspective, so that when you step out you do so with the complete picture.