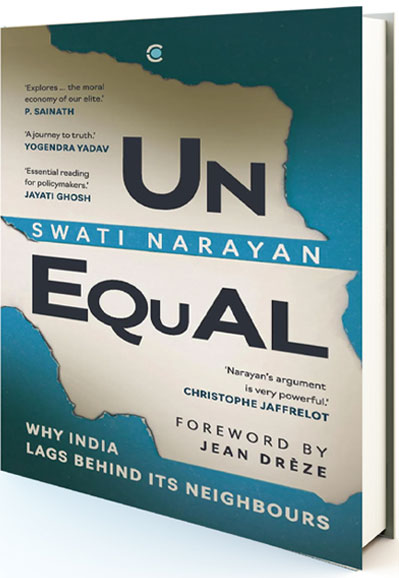

Extreme Inequalities

Until these inequalities are bridged, it is impossible for the nation as a whole to prosper, let alone be a world leader. An extract

Swati Narayan

Her sleeveless dress and quiet confidence were a breath of fresh air in the dusty, ramshackle home. Most of the other women in this family, from the Dom caste, were dressed in crumpled saris. Ranu’s husband, Jitu, too, in his smart shorts looked completely out of place in this remote Bihari village. After we struck up a conversation, I realized that the young couple had just crossed the open border, less than a kilometre away, from Nepal to Bihar on a day trip to visit their family.

Her sleeveless dress and quiet confidence were a breath of fresh air in the dusty, ramshackle home. Most of the other women in this family, from the Dom caste, were dressed in crumpled saris. Ranu’s husband, Jitu, too, in his smart shorts looked completely out of place in this remote Bihari village. After we struck up a conversation, I realized that the young couple had just crossed the open border, less than a kilometre away, from Nepal to Bihar on a day trip to visit their family.

The contrasts between these relatives who lived on different sides of the international border could not have been starker. In Kathmandu, Renu worked in a private canteen, while Jitu was a mechanic. The young couple were upwardly mobile and in good health and spirits. As a Nepali, Renu’s education in government schools had been free until grade eight. Every time her nine-month-old infant fell ill, she confidently took her to a nearby government health post for free treatment. The brimming self-assurance of this bright, young Dalit couple was not an exception, Since the return of democracy in 2006, as my research even a decade later showed, Nepal has witnessed an unmistakeable improvement in caste and gender equations.

Their Indian relatives, on the other hand, were struggling to eke out a living. Renu’s sister-in-law Malati, who was born in Nepal and had shifted to India two decades ago after marriage, complained about the caste discrimination that her children faced in school. She also confided that she was petrified of her family falling ill. In this Bihari hi

Subscribe To Force

Fuel Fearless Journalism with Your Yearly Subscription

SUBSCRIBE NOW

We don’t tell you how to do your job…

But we put the environment in which you do your job in perspective, so that when you step out you do so with the complete picture.

VIDEO

VIDEO